An Analysis of Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Jan Aushadhi Pariyojana (PMBJP)

- In Economics

- 08:06 PM, Jan 25, 2021

- Mukul Asher and Kruti Upadhyay

Theme

India’s central government-initiated Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Jan Aushadhi Pariyojana (PMBJP) to provide medicines and surgical items of good quality at affordable prices through the Jan Aushadhi Kendras in 2014 to wide section of the population.

An earlier attempt in this direction in 2008 was unsuccessful due to supply side and logistics management problems. The PMBJP was revamped in 2015 to address the shortcomings. The revamped scheme provides financial incentives to store owners.

Implementation and therefore operational accountability of the PMBJP is with the Bureau of Pharma PSUs (Public Sector Undertakings) of India (BPPI).

Revamped PMBJP is a part of the innovative approach to social protection which has been initiated by the Prime Minister Narendra Modi led government since being given the responsibility for governance in 2014 (Asher, 2019)

It recognizes that citizens, particularly the elderly, need access to a bundle of goods and services, and not just money; and that technology can be adapted to make them more accessible and affordable1.

India’s generic medicines industry is globally recognized and its product accepted. India reportedly accounts for around one-fifth of the global exports of generic medicines. In 2019-20 India pharma exports were USD 19.8 Billion.

It is reported that over 90 countries have enquired about Indian vaccines. This demonstrates international confidence and acceptance of Made-in-India medicines. India has donated vaccines to several neighboring countries. A request by Brazil for two million dozes of COVID-19 vaccines, involving those from the Indian company Bharat Biotech International Limited (Covaxin), and AstraZeneca and University of Oxford (Covishield), produced by the Serum Institute of India (SII) has been honored on a commercial basis. More such commercial exports requests are to be executed.

India has taken only six days to administer more than one million doses of vaccines against COVID-19. This makes it the fastest rollout of a million vaccine shots against the pandemic among countries that have placed their inoculation data in the public domain.

Key Economic Reasoning concepts

There are three key economic reasoning concepts applicable in analyzing the PMBJP. This will be evident in the analysis.

First, the primary socio-economic role of public sector organizations is to make accessible, affordable, reasonable quality goods, services or amenities available to the citizens reduce the monopoly power of other suppliers.

Effective competition is the single most important spur to efficiency. This also requires adapting newer technologies, including in organizational structures and processes, and in managing supply and logistics chains, as they emerge.

Second, for a household, a reduction in total cost of obtaining a good or a service, such as medicines, whose share of household budget increases after 60 years of age, is equivalent to increasing its income. But this requires that they be accessible, affordable, and of acceptable quality.

Third, the concept of learning curve needs to be operationalized. This concept is derived from engineering economics. It measures the extent to which as cumulative output increases, per unit requirement of key inputs, such as labor units decline. This concept needs to be applied to public sector organization in India delivering goods, amenities and services.

The efficiencies arising from the learning curve are in addition to economies of scale efficiencies, where a scale of operations, for example of PMBJP increases, per unit costs should exhibit a decline. These efficiencies however need to be measures by appropriate management information system.

The Context

The COVID-19 pandemic has underlined the importance of constructing a robust public and private health care system globally, as well as in India. India is also undergoing a disease-burden transition from communicable to more-life-style related diseases where more complex heath systems are even more essential.

As in other areas, expectations and aspirations of the Indian citizens for better quality of health care and medical and surgical items has been rising, which need to be addressed.

One of the indicators of how a country organizes a health care system is the share of out-of- pocket expenditure (OOPE) as share of total health expenditure in the country. India’s share, while declining, was in 2018 at around 60% of the total is on a high side, and needs to significantly decline further 2.

According to a study by Singh et. al. (2020) medicines and surgical items, i.e., pharmaceuticals, contribute 43 percent to the total out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) on health in 2015-16, with significant variations across states. This makes it the single largest category under OOPE, followed by expenditure incurred in private hospitals, medical diagnostics, government hospitals, and general medical practitioners, in that order.

The Brookings study argues that the OOPE warrants special attention as it leads to impoverishment, with 7% of the households falling below the poverty line on account of health expenses3.

Making medicines accessible and affordable, without persons needing to borrow, and in some cases being pushed to low-income status, should be among the KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) of the PMBJP. This initiative could also help India progress towards achieving universal health coverage by 2030.

Design and Implementation OF PMBJP

The information in this sub-section is primarily from4.Even though, the Jan Aushadhi was launched in the year 2008, at the time of the 2015 revamping, PMBJP comprised only 80 functional stores across the country. Remaining stores were either non-functional or shut down due to various reasons such as poor support from state governments, poor supply chain management, non-prescription of generic medicines by the doctors, and lack of awareness.

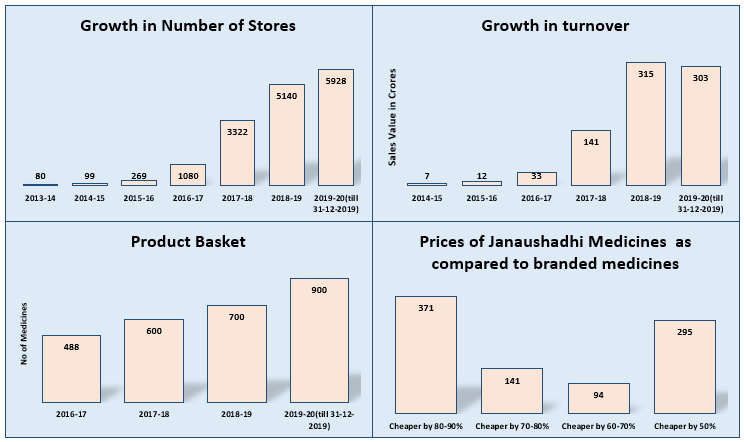

Since 2015, the number of the stores have grown from 80 to more than 6600 spread across over 700 districts by end 2020. As may be expected, maximum expansion of stores is in urban districts, areas of high literacy and high level of development. The establishment of stores is driven by considerations of potential market size and resulting profits. Most districts in 2019 had at least one store but few Northeastern and Central districts have no stores. This aspect needs addressing.

Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers has indicated that it plans to make 10,500 PMBJP stores functional by March 2024.

As at end 2020, four warehouses of Jan Aushadhi Kendras are functional at Gurugram, Chennai, Bengaluru and Guwahati. Two more warehouses are planned in Western and Central India to improve efficiency of the supply chain system. Bureau of Pharma PSUs of India (BPPI), the implementing agency of the PMBJP is responsible for setting up the new Kendras.

An individual entrepreneur who opens PMBJP kendra of eligible to receive an incentive of 15 percent of monthly purchases (subject to ceilings).

As at end 2020, the product basket consists of more than 800 drugs and 154 surgical instruments. The medicines are procured from World Health Organization – Good Manufacturing Practices (WHO-GMP) certified suppliers. Also, each batch of the drug is tested at ‘National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories’ (NABL) accredited labs. Medicines are dispatched to the Kendras only after they pass the quality test5,6.

A medicine under PMBJP is priced on the principle of a maximum of 50% of the average price of top three branded medicines. Therefore, the cost of the Jan Aushadhi Medicine is cheaper at least by 50% and in some cases, by 80 to 90% of the market price of branded medicines7.

The above does suggest that customers pay significantly less from PMBJP related stores than what they need to pay for same medicines (technically) from other sources.

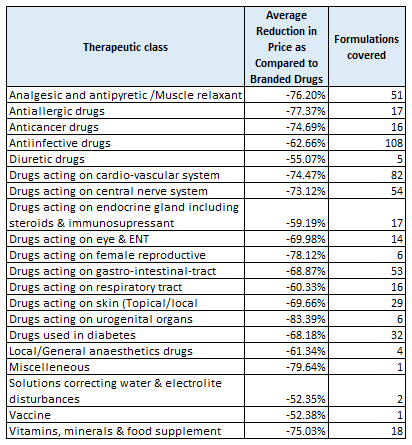

Table 1: Average price benefits of Jan Aushadhi stores

Source: “Medicines in India: Accessibility, Affordability and Quality,” Brookings India Research Paper No. 032020-01- Accessed on 21 January 2021

Table 1 provides average reduction of generis drug price as compared to branded drugs classified by therapeutic classes.

“Formulations covered” column shows the number of generic medicines falling under any particular therapeutic class. “Average reduction in price as compared to branded drugs” column shows the average percentage difference between average price of top three branded medicines and the generic drugs of the same therapeutic class.

Data in Table 1 suggest that minimum average percent of the price decrease is 52.35% for the drugs falling under Solutions correcting water & electrolyte disturbances therapeutic class compared to top three branded medicines. Drugs acting on urogenital organs - therapeutic class has maximum average percent decrease in prices compared to top three branded medicines.

The same study compares some basic medicines used for lifelong disease such as thyroid, blood pressure and diabetes. Let us assume there is a patient who has been prescribed Telmisartan (40mg). If the person uses the medicines purchased from the kendra, she will save approximately INR 2300 per year. For a person living below poverty line this will make approximately 3 percent of the income saved per year.

Any expenditure saved on medicines and surgical items by a household is same as increase in household income. The PMBJP thus can be cumulatively be expected to significantly raise income of the bottom half of the population.

Revenue from medicines and surgical items by the kendras has grown rapidly from INR 73 million in 2014-15 to Rs. 3030 million till 31 December 2019 as per the annual report of the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers. It is important to note that kendras marketed merchandise worth INR 3580 Million during first 7 seven months of the FY 2020-21. Kendras are estimated to achieve sales of more than INR 6000 million for the entire FY 2020-21. This suggests promising potential for expanding revenue from the Kendras8.

Progress of PMBJP since 2013-14 is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Select Indicators of the PMBJP9

Future Directions

THE PMBJP will not only tap efficiencies from economies of scale it expands, but also become competent as an organization to competently ride the learning curve, as cumulative output expands.

In the 2020 Budget, the Finance Minister proposed expansion of PMBJP to all districts, with offering of 2000 medicines and 300 surgical items by 2024.

To set up robust logistic and supply chain for such large number of stores spread across the country, and for such large of medicines and surgical items in such a short period would be a challenging task. As noted, there is promising potential to enhance revenue generation from the Kendras. This requires robust financial management system.

It is strongly urged that a robust MIS (management Information System) be established for MIS to assist in better management and decision-making, and to monitor key results and outcomes. The MIS should also provide the ratio of revenue generated over expenditure incurred on PMBJP. This ratio should be increasing overtime.

Such MIS would also help in competitiveness of PMBJP with other supply chains, and help estimate real economic savings to the consumers, to the economy, and to medicine production industry.

The number of Jan Aushadhi kendras should be spread out more evenly among urban, para-urban, and rural areas for better accessibility.

The kendras need to be incentivized to upgrade their technology of supply chain and delivery mechanisms, and add more revenue generating added services to those who value them, while creating trust in them.

It is also urged that the health departments at all levels of government procure generis medicines wherever feasible, and educate doctors, nurses, general public and others about them.

The researchers in health policy and practices are strongly urged to make use of data from the PMBJP link, and to collect primary data to critically evaluate the progress of PMBJP, and how it can better attain its objectives.

References

- https://www.myind.net/Home/viewArticle/indias-integrated-and-innovative-approach-to-old-age-security -Accessed on 2 December, 2020

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS -Accessed on 20 December 2020

- Medicines in India: Accessibility, affordability and quality (brookings.edu) -Accessed on 25 December 2020

- http://janaushadhi.gov.in/Data/Annual%20Report%202019-20_21052020.pdf- Accessed on 12 December 2020

- http://janaushadhi.gov.in/Data/Annual%20Report%202019-20_21052020.pdf

- https://swarajyamag.com/insta/boost-to-affordable-medicines-govt-to-increase-number-of-janaushadhi-kendras-to-10500-by-march-2024 -Accessed on 12 December 2020

- http://janaushadhi.gov.in/Data/Annual%20Report%202019-20_21052020.pdf

- https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/pharmaceuticals/pharma-products-worth-rs-358-cr-sold-through-jan-aushadhi-stores-in-april-october/articleshow/79025013.cms -Accessed on 12 December 2020

- http://janaushadhi.gov.in/Data/Annual%20Report%202019-20_21052020.pdf -Accessed on 12 December 2020

Asher, Mukul G. (2019). “India’s Integrated and Innovative Approach to Old Age Security”, https://myind.net/Home/viewArticle/indias-integrated-and-innovative-approach-to-old-age-security -Accessed on 21 July 2021

Singh, Prachi, Shamika Ravi, and David Dam,2020. “Medicines in India”, Brookings India Medicines in India: Accessibility, affordability and quality (brookings.edu) -Accessed on 12 January 2021

Image Source: National Portal of India

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. MyIndMakers is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information on this article. All information is provided on an as-is basis. The information, facts or opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of MyindMakers and it does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Comments