Why Large Mammals like Elephants Still Exist in India — A Clue from Ṛg-Veda, Smṛtis, Rāmāyaṇa and Sūtras

- In History & Culture

- 12:22 PM, Mar 07, 2023

- Rupa Bhaty

If there is an effect there has to be a cause behind that effect. Before understanding why mammals like elephants and tigers still exist in India let’s do a comparative study of Elephants in Ṛg-Veda and Rāmāyaṇa

Elephants in Ṛg-Veda

In Ṛg-Veda elephants had few synonyms like Mṛga Hastin, Ibha, Mṛga Vāraṇa, which respectively means beast with a hand, fearless and wild or dangerous animal. The elephant is called hastin in classical Sanskrit texts and is probably one of the most ancient names coined for elephants which come from Ṛg-Vedic “mṛga — hastin”. Etymologically, Mṛga comes from the root √mṛga—anveṣaṇe, which generally would mean search, explore, etc. By the onomastic approach, mṛga would rather mean only chasing and hunting, even a few birds from Ṛg-Veda are assigned to this word. It thus is explicitly used for the beasts which were eventually to be named, and also to the earliest astronomical figures in the sky which appeared like chasing the former observed during the rotation and revolution of the earth. Sanskrit thus gives us mṛga as a common name for the beasts, further Ṛg-Veda records a beast with a hand-like extension for elephants. The word Hastin, though not in a pure compound sense, appears in the 4th maṇḍala which is ascribed as one of the middle maṇḍalas of Ṛg-Veda.

Mṛga iva Hastin

Mṛga iva Hastin (animal with a hand) occurs in Ṛg-Veda 1.64.7 and Ṛg-Veda 4.16.14.

म॒हि॒षासो॑ मा॒यिन॑श्चि॒त्रभा॑नवो गि॒रयो॒ न स्वत॑वसो रघु॒ष्यद॑: ।

मृ॒गा इ॑व ह॒स्तिन॑: खादथा॒ वना॒ यदारु॑णीषु॒ तवि॑षी॒रयु॑ग्ध्वम् ॥ ऋ० ००१।०६४।००७

“Vast, possessed of knowledge, bright-shining, like mountains in stability and quick in motion, you, like elephants, break down the forests when you put vigour into your ruddy (mares).”

The phrase "beast with a hand" is used to refer to the elephant, but the author concludes that the compound name is evidence of the elephant's novelty to the Vedic Indians. Even in the aforementioned mantras, it remains an untamed beast.

Ibha; The fearless

Ibha, which means fearless by Sāyanāchārya, appears to be the first ever to have been tamed as found in later literature text. The word is present in Ṛg-Veda but conspicuously absent in Rāmāyana. It does appear in Raghuvaṃśam giving a hint that Kālidāsa knows where to use it and what was its kind.

कृ॒णु॒ष्व पाज॒: प्रसि॑तिं॒ न पृ॒थ्वीं या॒हि राजे॒वाम॑वाँ॒ इभे॑न ।

तृ॒ष्वीमनु॒ प्रसि॑तिं द्रूणा॒नोऽस्ता॑सि॒ विध्य॑ र॒क्षस॒स्तपि॑ष्ठैः ॥ ऋ० ०४।००४।००१

“Put forth thy strength, Agni, as a fowler, spreads a capacious snare: proceed like a king followed by his followers on (or alongside; case 3 इभे॑न) his elephant: thou art the scatterer (of thy foes): following the swift-moving host consume the Rakshasas with thy fiercest flames.” [Translation By HH Wilson. Ṛg-veda 4.4.1]

Here elephant appears to have been used as a scatterer and has been equated with the forest fire. This mantra is tricky to understand. Case 3 vibhakti captures the idea of the English word “with,” in two senses of the word “with.” The two senses are- means, as in “I hit the coconut with my hammer” and accompaniment, as in “I hit the coconut with my friend.”

गजेन गच्छामि, I go by means of (with) the elephant

गजेन गच्छामि, I go alongside (with) the elephant

Overall, alongside of the elephants would only mean that it was not a tamed animal in Ṛg-Veda. Lexicon says इभ as servants, dependents, domestics, household, family. It is attested by böhtlingk and roth Sanskrit wörterbuch on the merits of translation as the third case. Fearless says Sāyanācārya. The elephant is used as a scatterer and appears to be not yet tamed.

Mṛga-Vāraṇa; shy and forbidden

Another term that may mean elephant is “Vāraṇa” (ṚV. 8.33.8; ṚV. 10.40.4). According to Macdonell and Keith, “Vāraṇa” refers to elephants, the descriptive term Mṛga - Vāraṇa, the wild or dangerous animal.

दा॒ना मृ॒गो न वा॑र॒णः पु॑रु॒त्रा च॒रथं॑ दधे ।

नकि॑ष्ट्वा॒ नि य॑म॒दा सु॒ते ग॑मो म॒हाँश्च॑र॒स्योज॑सा ॥ऋ० ०८।०३३।०८

“As a wild elephant emitting the dews of passion, he manifests his exhilaration in many plural ces; no one checks you, (Indra), come to the libation; you are mighty, and goes (everywhere) through your strength.”

यु॒वां मृ॒गेव॑ वार॒णा मृ॑ग॒ण्यवो॑ दो॒षा वस्तो॑र्ह॒विषा॒ नि ह्व॑यामहे । ...ऋ० १०।०४०।००४

“Like persons hunting two wild elephants, we praise you, Aśvins, with oblations night and day; at all due seasons, leaders (of rites), (the worshipper) offers you the oblation; do you, who are rulers of the shining (rain), bring food to mankind.”

Vāraṇa means warding off, restraining, resisting, opposing; all-resisting, invincible (lexicographer notes Soma and of Indra's elephant RV. ix, 1, 9); relating to prevention; shy, wild, dangerous; forbidden;

The “mṛga/wild animal” adjective to Vāraṇa is similar to Hastin which becomes a synonym for the noun ‘elephant’ in the later texts. In the later Paurāṇica and Aitihāsika texts we find that Indra is associated with four tusked elephants. Ṛg-Veda doesn’t say that Vāraṇa is a four-tusked elephant. We need some more evidence to come to a conclusion if this word was used for the same.

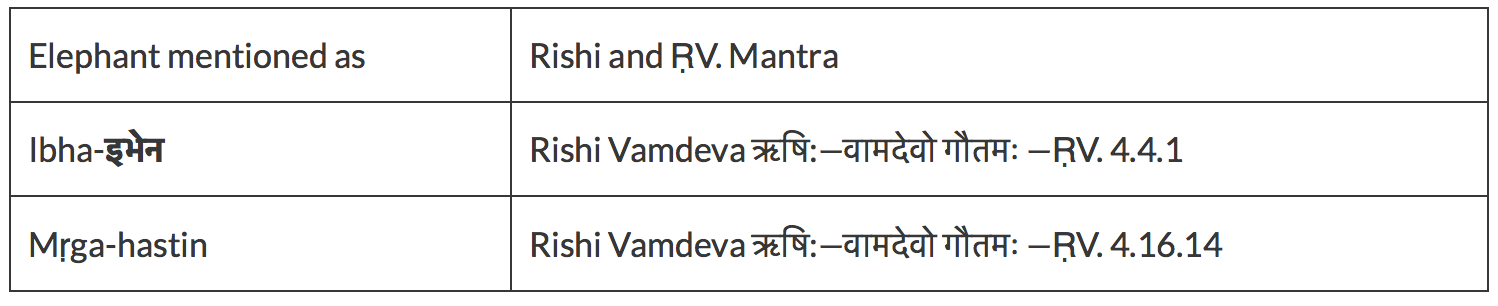

Presence of Ibha and Mṛga hastin in 4th mandala

The same Rishi is responsible for both Ibha and Mṛga - hastin, but he did not invent the word “Hastin" as a noun. Instead, he used it as an adjective to describe the Mṛga - wild beast. So, it seems unlikely to me that Ibha is employed in Ṛg-Veda 4.4.1 as a wholly invented word to refer to any species of elephant. The same rishi wouldn't first identify an elephant before misidentifying it. In the Vedic land, they had begun to distinguish between various animals they were observing. Then Palaeoloxodon Namadicus appears, which is actually a beast with enormous straight lethal ivory tusks that is terrible, unstoppable, and cannot be tamed. I identify it with Ibha. Since when I studied the etymological aspect of Ibha and Ivory with European, and African linguistic patterns it matched perfectly with Ṛg-Vedic Ibha. The Ganga plain in India is where a late report of its discovery dating from 56,000 years before present (BP) is known. A species of Pleistocene Asian elephant known as the Asian straight-tusked elephant ranged from India, where it was originally discovered, to Japan.

We also discover that Rāmāyaṇa knew about four-tusked elephants, which may have been yet another species that the Ṛg-Vedins were familiar with. We cannot remember which elephant received which name. Till now we have gathered knowledge that Ṛg-Veda has not yet tamed the elephants. Now let’s see what Rāmāyaṇa has to offer in the case of various types of elephants.

Elephants in Rāmāyaṇa

Elephants in Rāmāyaṇa are tamed and domesticated too as they are mentioned to be interbred.

भद्रैः मन्द्रैः मृगैः च एव भद्र मन्द्र मृगैः थथा |

भद्र मन्द्रैः भद्र मृगैः मृग मन्द्रैः च सा पुरी || १-६-२५

नित्य मत्तैः सदा पूर्णा नागैः अचल सन्निभैः |

That city is always full of vigorous and mountain-like elephants bred mainly from three classes viz., Bhadra, Mandra and Mṛga. And interbred among these three main classes are Bhadra-Mandra, Mandra-Mṛga, Bhadra-Mṛga, and the like. [1-6-25-26a] Rāmāyaṇa

वारणैश्च चतुर्दन्तैः श्वेताभ्रनिचयोपमैः।।५।४।२७।।

That place looked splendid with four tusked elephants resembling heaps of white clouds. (pratyakṣa, i.e., direct cognition seen by Hanumāna)

रामेण सङ्गता सीता भास्करेण प्रभा यथा राघवश्च मया दृष्टश्चतुर्दष्ट्रं महागजम्।।5.27.12।।आरूढ श्शैलसङ्काशं चचार सहलक्ष्मणः।”

Just as light is united with the Sun, I saw Sita united with Rama. I saw Rama with Lakshmana riding a huge, mountain-like elephant having four tusks.

ततस्तस्य नगस्याग्रे ह्याकाशस्थस्य दन्तिनः।।५।२७।१४।।

Then from the front of the mountain, Janaki shifted to the back of the elephant held by her husband waiting in the sky.

चतुर्दन्तं गजं दिव्यमास्ते तत्र विभीषणः।।५।२७।३३।।

Vibhishana was seen ascending onto a decorated four-tusked elephant (Trijaṭā, a servant of Rāvaṇa, cognizes four-tusked elephant in a dream state)

Rāmāyaṇa also records elephants found in different directions who were the dikpālas (guardians of direction) of four directions. Virūpākṣa (east), Mahāpadmasama (south), Saumanasa (west), and Bhadra (north) in Bālakāṇḍa. It is noted that the elephants bred mainly from three classes viz., Bhadra, Mandra and Mṛga, out of which we find Bhadra hailed from the north. Here Bhadra attests that all four including Bhadra were species from different regions.

Comparative studies

Mṛga iva hastin transforms into proper nouns like Mṛga and Hasti. We find that Ibha is no more mentioned in Rāmāyaṇa. Vāraṇa is mentioned in the context of a four-tusked elephant in Rāmāyaṇa. My interest is in finding if Vāraṇa, as a distinct species of four-tusked elephant, was the name given to the elephants in Ṛg-Veda. And it is clear from the above studies that indeed Vāraṇa was still in a naming phase in Ṛg-Veda but was used for the four-tusked Elephant (gomphothere) in Rāmāyaṇa, an invincible mounting animal of Indra in later references (like MBH and other Indic texts), which was to be forbidden (Aitereya Brāhmaṇa) purposely and apparently for the causes like for its wildness, non-interbred-ness., etc. The Mṛga iva Vāraṇa indeed gets the name Vāraṇa post Ṛg-Veda in Rāmāyaṇa times, which is evident by its usage, which initially was associated with Soma and Indra in Ṛg-Veda. Later we find the myths of four tusked Airāvata (but also seven heads) where Ṛg-Vedic Mṛga-Vāraṇa appears to be a precursor to it.

Rāmāyaṇa through Ṛg-Vedic times have been recording and encoding the then-surrounding realities of flora and faunas in a very meticulous way. Probably, you may have read one of my blogs about lions and tigers, their presence and absence in the Vedas, and their subsequent noticeable presence in the Rāmāyaṇa. Read blog “The Majestic Lions in Ṛg-veda, and Curious Case of Absence of Tigers in Ṛg-veda; What do these suggests…” — here.

In the continuation to the thought of antiquity of evolution of naming and taming of different species of elephants I came across an article “Yale study finds why large mammals like elephants; tigers still exist in India” in the e-paper; The Print. First, of its kind, the study finds that the rate of extinction of animals weighing over 50 kg over the past 30,000 years is the lowest in India and points to the co-evolution of humans and mammals. A new collaborative study from Yale University, Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, George Mason University, and the University of Nebraska, based on data from 51 fossil sites in today’s India, documents the Late Quaternary megafauna extinction in India. The paper shows that the extinction rate in India and Africa over the past 50,000 years is 2.5 times lower than in South America, and nearly 4 times lower than in North America, Europe, Madagascar, and Australia. This indeed was a curious case as to how modern human behavior had been in India in such deep antiquity. I craved for answers as to what were the thoughts that restricted the humans of our subcontinent to kill such beastly and ferocious mammals in those times. I had already written a blog on Elephants that are still shy beasts in Ṛg-Veda. In Ṛg-Veda we don’t recall Indra on an elephant but it is available in Itihāsās and Purāṇa history. See, Surya’s chariot crushing a demon (left) and an elephant rider, probably Indra (right), in Cave 19[1] from Bhaja Dist, Pune.

Instead, horses were liked and mounted by the deity Indra in Ṛg-Veda and the latest maṇḍala gives a hint to the elephant’s association with Soma and Indra had begun. This gave me a thought to see into how Ṛg-Veda perceives elephants differently from Rāmāyaṇa and in the previous section I have discussed the evolution in the naming process and encoding of the then realities of elephants from wild to being tamed and bred.

For the above quote, only two things offer us the best answers for which the beasts survived quite well in India. Even the Four tusked elephants survived in India till Rāmāyaṇa times (ref. Ram Ravan Yuddha-12209 BCE by Shri Nilesh Oak). Sundar Kāṇḍa [4.27. 12] states that Lord Hanumān, on entering Lankā, sees four-tusked elephants guarding the palaces of Rāvana. These elephants are tall and imposing and have been trained to protect Lankā from invaders.

Either the haven for such creatures is highly suitable, Or, there had been a culture to protect these beasts.

पञ्च पञ्च नखा भक्ष्या ब्रह्मक्षत्रेण राघव।।

शल्यक श्श्वाविधो गोधा शशः कूर्मश्च पञ्चमः।

‘O Rama brahmins and kshatriyas are permitted to eat only the five nailed animals the porcupine, the hedgehog, the alligator, the rabbit and the tortoise. — 4.17.38—Rāmāyaṇa

There are indications from around the world that the bone marrow of elephants was eaten till 40,000 years ago. Humans that populated the banks of the river Manzanares (Madrid, Spain) during the Middle Palaeolithic (between 127,000 and 40,000 years ago) fed themselves on pachyderm meat and bone marrow. This is what a Spanish study shows and has found percussion and cut marks on elephant remains in the site of Preresa (Madrid). — read here. Fat and protein have been recognized as essential elements for human diet during the Pleistocene ….Lower Palaeolithic stone hand-axes, and the peculiar presence of hand-axes made of elephant bone— read here. The Indian culture of consuming elephant meat or bone marrow may only be understood if archaeological evidence of an elephant bone hand axe is discovered, if one was ever constructed in India. Because elephants had five toes, they were prohibited from being eaten throughout the Rāmāyaṇa period.

After Indra’s conveyance transformed from horse to elephant in the Puranas, we find the Ganesha Culture. Such a culture also forbids the slaughter and disposal of animals that may have played a vital part in maintaining the ecological balance. Tigers, on the other hand, are Durga’s vehicle and are sometimes depicted with the lion also.

Note: Cloven-hoofed (two-toed) like deer, etc., were medhayan—consecrated, to be eaten.

Manusmṛti says

Manusmṛti also endorses the same that five-toed animals should not be eaten.

न भक्षयेदेकचरानज्ञातांश्च मृगद्विजान् ।

भक्ष्येष्वपि समुद्दिष्टान् सर्वान् पञ्चनखांस्तथा ॥ १७ ॥

He shall not eat solitary animals, nor unknown beasts and birds, even though indicated among those fit to be eaten; nor any five-nailed animals— (17).

Other references and comparative notes by various authors are given below. It explicitly notes that useful mammals and animals were left from being killed from time to time.

Comparative notes by various authors of different texts

Gautama (17-27) — ‘Five-nailed animals should not be eaten, excepting the hedgehog, hare, the porcupine, the iguana, the rhinoceros and the tortoise.’

Baudhāyana (1.12-5) — ‘Five five-nailed animals may be eaten—viz., the porcupine, the iguana, the hare, the hedge-hog, the tortoise and the rhinoceros, except (perhaps) the rhinoceros.’

Āpastamba (1.17-37) —‘Five-nailed animals should not be eaten, excepting the iguana, tortoise, the porcupine, the rhinoceros, the hare and the Putīkaśa.’

Vaśiṣṭha (14.39, 40, 44, 47) —‘Among five-nailed animals, porcupine, the hedgehog, the hare, the tortoise and the iguana may be eaten; among domestic animals, those having only one row of teeth, except the camel; those not mentioned as fit for eating should not be eaten; regarding the wild boar and the rhinoceros, there are conflicting opinions.’

Viṣṇu (51.6, 26, 27) —‘On eating the flesh of five-nailed animals,—except hare, the porcupine, the hedgehog, the rhinoceros and the tortoise,—one should fast seven days; on eating the flesh of the ass, the camel and the crow, one should perform the Cāndrāyana,—also on eating unknown flesh, or flesh from the slaughter-house, or dried flesh.’

Yājñavalkya (1.174, 177) — ‘Unknown animals and birds, flesh from the slaughterhouse and dried flesh (should not be eaten). Among five-nailed animals, the following may be eaten: the porcupine, the hedgehog, the alligator, the tortoise and the hare.’

Devala (Vīramitrodaya-Āhnika, p. 543) — ‘Among animals, the following should not be eaten: the cow, the camel, the ass, the horse, the elephant, the lion, the leopard, the bear, the Śarubha, serpents and boa constrictors, the rat, the mouse, the cat, the mongoose, the village-hog, the dog, the jackal, the tiger, the black-faced monkey, the man and the monkey.’ (source-Wisdomlib.org)

Takeaway

From the above studies, one can infer that Rāmāyaṇa through Ṛg-Vedic times have been recording and encoding the then-surrounding realities of flora and faunas very ardently. We also see that the growth of language and usage of words were getting firmer in the later times, here in the context of the naming of various elephant species

Rāmāyaṇa gives us a very clear picture of why these beasts of more than 50 KGs survived in the Indian subcontinent. The study above explicitly shows that we have seen the transition in eating different types of meats as the general stapled food in our texts. Rāmāyaṇa times appear to have either lessened the five hoofed due to their experience of megafauna extinction worldwide or they incorporated only five of five hoofed beasts into their staple. After all, Ṛg-Vedins and then Rāmāyaṇa times people hail from the late Pleistocene times and upper to middle Paleolithic times.

[1]*"Close view of sculpture round doorway at right side of verandah of the small Buddhist Vihara, Bhaja Caves," a photo by Henry Cousens, c.1880* (BL); Site: http.columbia.edu

Title image source: HelloNRI, Text images provided by the author.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. MyIndMakers is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information on this article. All information is provided on an as-is basis. The information, facts or opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of MyindMakers and it does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Comments