When Teachers were Beaten to Death by Their Own Students

- In History & Culture

- 10:42 AM, Dec 09, 2022

- Sahana Singh

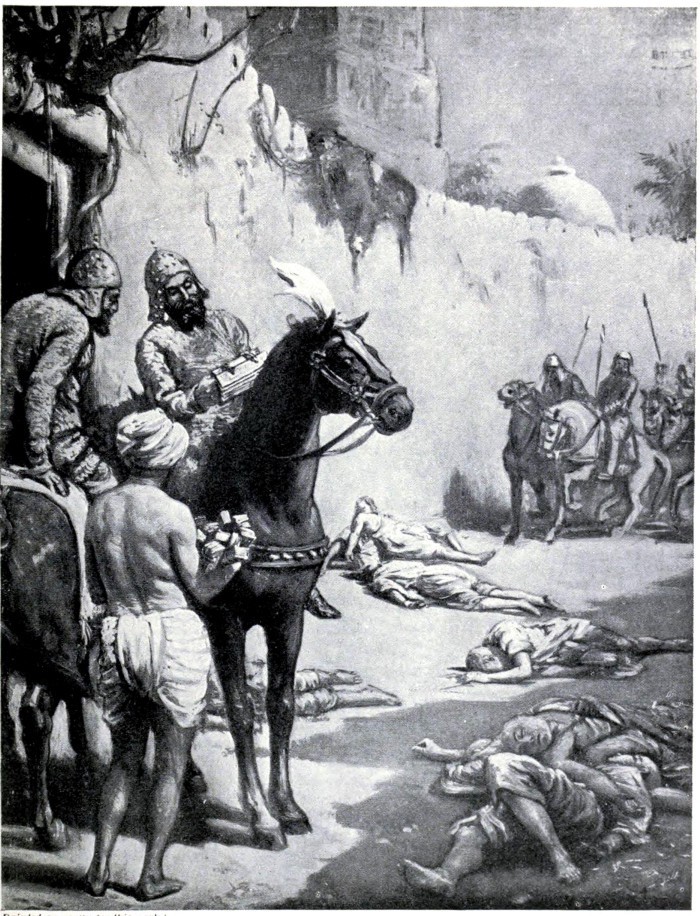

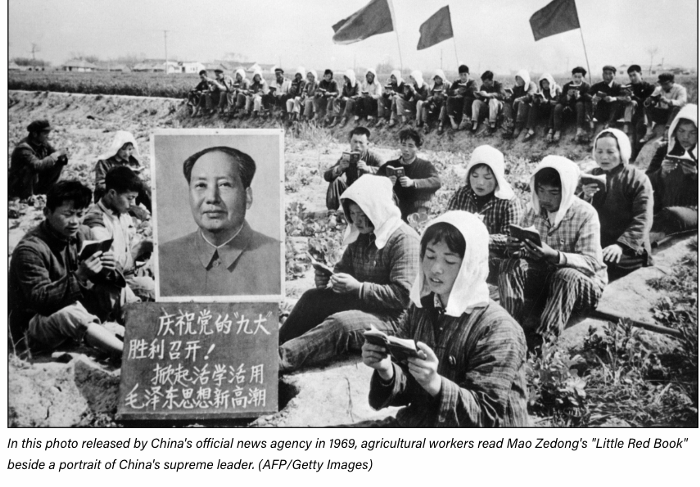

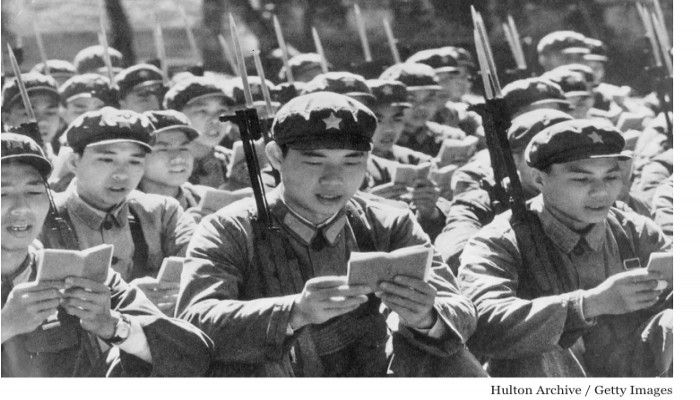

Red Guards of China with the Little Red Book that contained quotations from Chairman Mao

Yesterday, I went to the screening of a Chinese documentary titled “I don’t quite recall”. Directed by German-born Zhou Qing, the film focussed on memories of the Cultural Revolution in China in which millions of teachers and intellectuals were murdered. Years ago, when I did not know much about China’s history, I used to think that the words “Cultural Revolution” referred to some period of the revival of Chinese culture. When I came to know what it stood for, I was shocked. But what I saw and heard in the film yesterday simply made my hair stand on end.

Of course, as one who writes about the history of India, I know what Hindus were subjected to during the Dark Ages of Islamic invasions. The destruction of the best universities of the time — Nalanda, Vikramshila, Odantapura, Vallabhi, Sharadapeeth and countless others; the burning of libraries, killing of scholars and the fleeing of survivors with manuscripts they wished to preserve — I have written about all this in my book: Revisiting the Educational Heritage of India.

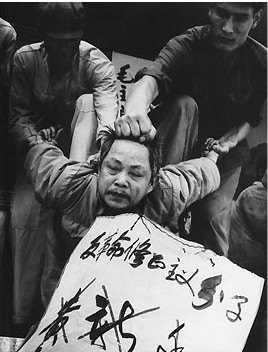

The picture of Mohammad Bakhtyar Khilji sitting on his horse and looking at a manuscript while bodies of students and scholars lie strewn before him — has haunted me from the time I saw it.

Sketch from Hutchison’s Story of the Nations edited by James Meston

But in the bloodbath that took place in China from 1967 to 1977, in the name of a cultural revolution, there were no invaders from outside. Students across the country were told by their government to attack and kill their own teachers! Teachers who taught them every day! In the film I saw, the generation of people, now in their 60s and 70s were interviewed to speak of their memories of the massacre.

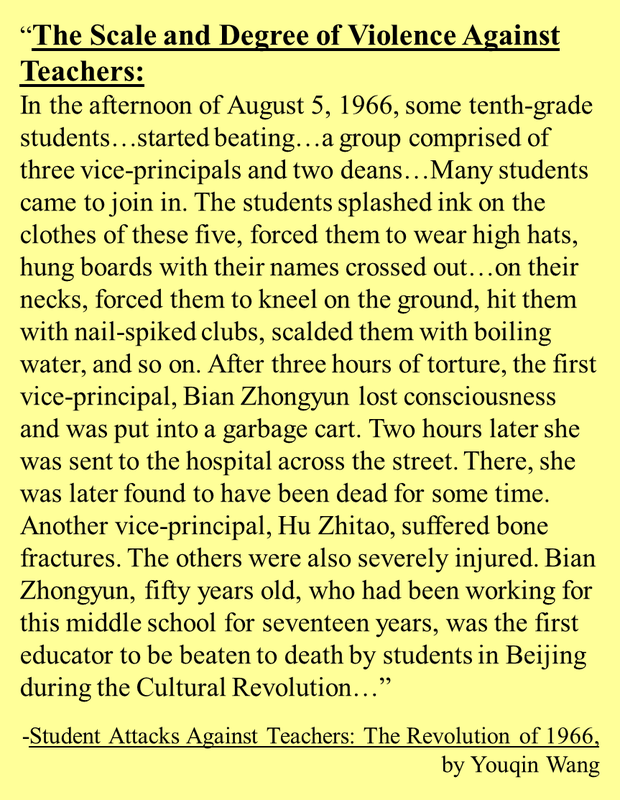

Most of them started by saying they could not recall (hence the name of the film). It was as if they had deliberately forced amnesia on themselves. They said no one talked about it anymore and it was a forgotten period of history. But after persistent questioning, the stories came out. They described scenes of teachers being rounded up and half their heads shaved as a sign of humiliation. In some cases, the violence would be initiated by boys who had a grouse against some teacher and other students would join him in bludgeoning the teacher. In other cases, a teacher would be denounced as an elitist and even as she protested that she was from the peasant class too, her attackers would pounce upon her.

One person recalled how his classmates had made a teacher stand atop four desks piled over each other. After she climbed to the top, the desks were removed and she fell from a height smashing her face. Yet, she was forced to climb up again and fall in the same manner. They did this until she was lifeless. Many of the students wore the Red Guards armbands to show their solidarity with Chairman Mao. Girls displayed as much cruelty as boys and did not lag behind in finding new ways of torturing their teachers.

Across China, more than 1.5 million teachers were killed according to the documentary. Many of them committed suicide after public humiliation. As news spread about beating incidents in different schools, students from more schools began to join in. The teachers who survived the beatings and humiliation were sent to far-off labour camps. Schools and colleges were ultimately shut down. It was a lost decade.

Thanks to Youquin Wang, who moved out of China to the United States in 1988, the untold stories of the murdered teachers began to be finally documented. She was 13 years old when she witnessed her classmates beating their middle school vice principal to death. Later, she became a professor at the University of Chicago and was one of the first to carry out detailed research on the Teacher Holocaust that took place during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Her paper can be read here. She writes:

These violent attacks on campuses, however, have not been reported for various reasons. In the summer of 1966, when these events occurred, not a word concerning the violence was ever mentioned in the Chinese media, despite the fact that the media enthusiastically hailed the “Red Guards” (紅衛兵) — which had arisen nationwide in early August of 1966 — and reported their activities as headline news almost every day. From the newspapers, magazines, and documentary films published by Chinese authorities at that time, we can see pictures in which millions of teenagers wearing Red Guard armbands march through Tiananmen Square (天安門廣 場), with some Red Guard leaders applauding Mao Zedong who stands atop Tiananmen Gate. Against the red background of the red wall of Tiananmen Gate, Mao’s little red books, red flags, and red slogans, stood thousands of young, jubilant Red Guards forming a powerful, distinctive image of the Cultural Revolution. The bloody side of the Cultural Revolution was lost in the spectacular, uplifting image the media created. Nor were the deaths or torture reported by the Red Guard publications of that period.

In “I don’t quite recall” the interviewees wonder what was that era of madness that turned so many young people into monsters bereft of any human feelings. What was that mentality which compelled millions of students to take pride in beating up their teachers? The director brings out the fact that the Chinese love to speak about the great history of China but they simply gloss over the horrors of the Cultural Revolution.

I went home with a great sense of disquiet. Just two thousand years ago, China courted scholars from India with great passion. Countless teachers from India were invited to settle down in China so that they could help to translate hundreds of thousands of Sanskrit manuscripts into Chinese.

A significant number of Chinese students went to study in ancient Indian universities such as Nalanda, the most famous names being Fa Hien, Xuanzang and Yijing. A knowledge revolution was unleashed as works of Buddhist doctrine, mathematics, medicine, astronomy and a plethora of other subjects were translated. It was as if the Chinese would leave no stone unturned to gain knowledge.

And yet, a time of extreme madness came when the Chinese regarded teachers as their enemies? It is mindboggling that the grandparents of many young Chinese today were involved in either lynching their teachers or watching them being lynched.

China’s reign of terror under Mao must not be forgotten or treated as an isolated incident that will not happen again in any part of the world. The world is more connected today and social media tools are being used to gather together for many purposes including violent ones.

A powerful quote of Milan Kundera that was used in the documentary said:

The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.

All the images are provided by the author.

Comments