Tradition, Interrupted

- In History & Culture

- 10:40 AM, Feb 15, 2023

- Priyanka Kumar

2022 | CHICAGO, IL, USA

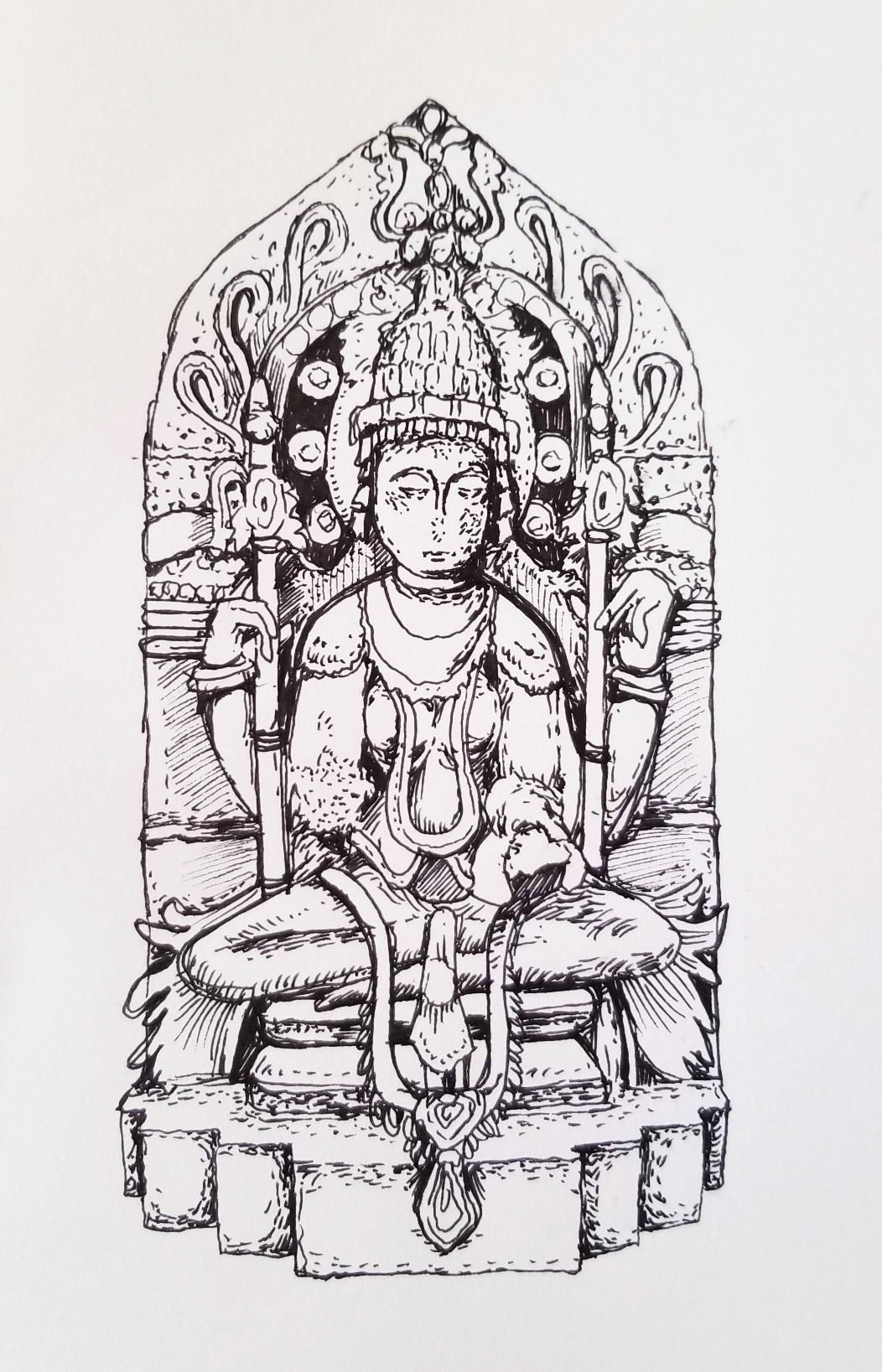

Her right forearm is broken. It catches my eye immediately.

Above the break is an intricate arm cuff. More heavy jewelery lines her neck and her torso, and one particularly long piece hangs off her lap. It complements the dhoti she wears, as she sits comfortably, but trapped. A heavy crown rests atop her head, although the weight of her confined reality feels more apparent. Eyes that were filled with life, when she was surrounded by those like her, are now hollow.

The room is filled with cold white light and muted whispers, punctuated by the occasional loud comment. It’s hard to pay attention to their sound when she sits there, a foot away from where I stand, but worlds apart.

Sarasvati, the Hindu Deity of Learning, Knowledge, and the Arts — carved during the Hoysala dynasty in the 12th century — sits expressionless, in the Art Institute of Chicago, a building separate from her original purpose, over 8000 miles away from where she was first sculpted.

Illustration of the Four-Armed Sarasvati on-view at the Art Institute of Chicago by Mariah Joyce

A part of me wonders what would happen if I reached out and touched her. Would her skin feel as cold as the carefully controlled room where she is kept? My hand almost extends out but stops—the ever-present barrier of museum etiquette reinforcing itself strongly, like an invisible yellow tape that it pretends not to be but functions as.

The last time I’d seen a Hoysala Deity in their home temple, it was under the hot South Indian sun. My father and I had visited it together during a TSD (Time-Speed-Distance) Rally in my home state of Karnataka, India. Like in the museum, I’d felt the same urge to reach out and feel their skin; to feel a tangible physical connection to the millions of people who had walked in the same footsteps for centuries. To know that we had been welcomed by the same Deities and lived our experience under the same sun.

Then I had simply reached out and touched their feet, felt the movement of the ornate carving under my fingertips, gently traced the curves and sinews of their forms. Every weathered skillful movement of the sculptors’ tools moulded to my touch, 800 years apart, yet timeless still.

Suddenly, as time begins once more, another visitor to the museum walks in front of me and I startle. The Art Institute of Chicago’s chilly air raises goosebumps on my arm and I think to myself that I should probably put my coat back on.

As I walk away, I can’t help but think back to the first time I saw this Sarasvati, of how I had stopped dead in my tracks. I’d recognized her — not just who she was, but also where she came from — without looking at her wall label. It was instinctual. Her artistic style was evident; I’d know the Hoysala sculptural tradition anywhere. I’d spent my childhood visiting temples that exemplified it and had particularly visited many in the last five years, after falling in love with them during an independent research project I did in high school.

Something clicked in that first moment of connection. Maybe it was the fact that I’d been reading about restitution and repatriation—about how many Western museums were reckoning with their colonial foundations and working to return or at the very least acknowledge cultural artifacts from Asian and African countries that had been unethically taken. Or maybe it was simply that I felt a kinship with her as an Indian woman living in the US, in a system that despite having lived here for the better part of my adult life, still felt foreign to me. Whatever it was, I knew that I was going to find out where she came from, how she got to the Art Institute, and how a white, non-Indian person was ever considered her legitimate owner.

Well, at the very least, I knew I was going to try.

*

This is the beginning to my long form, web-based essay, “The Price of Entry,” a project I undertook to fulfil my Master’s thesis. The essay is an exploration of my search to find the home temple of a Sarasvati murti that is presently housed in the Art Institute of Chicago, in the context of the debate surrounding the restitution and repatriation of artworks and artifacts from ancient and contemporary cultures that has swept the art world in the recent past.

Some of the biggest name museums all over the world are currently reckoning with the very real problem of the legality and legitimacy of their collections of foreign artworks; whether their provenance—a record of ownership of a work of art or an antique, used as a guide to authenticity or quality—is licit.

The unfortunate pattern that is emerging is that through the lens of what many museums refer to as the contemporary standards for proof of ownership, most of these murtis have been either smuggled illegally—think of the infamous Subhash Kapoor case—or were taken during times of colonisation and oppression. However, many museums, especially the bigger, more powerful ones, require a notable amount of proof that these so-called artworks and artifacts were in fact procured illegally, in order to restitute them. (Interesting that, often, history shows they weren’t as thorough when acquiring it in the first place).

Over the course of study there were a few issues that stood out as the pillars around which the debate about restituting antiquities lay. In the Indian context, the argument is quite simple.

Frequently, the question that many museums and academics who argue against the return of culturally important and significant creations—and in the case of India, Nepal and other South- Asian countries, representations of Deities, and living Gods—ask is, “What is best for the art?”

It is important to recognize that this language favours a Western perspective, framing something like a murti as an artwork, an object. If the question were to be flipped and phrased as “what is better for a murti,” the parameters of the dialogue automatically change.

Is it in fact better that murtis are kept in a sterile context, not worshipped as they are meant to be? Is it better for a murti that museum visitors see one in passing, spend a few minutes looking at the murti, then go on with their lives? Or is it better that the murti be revered as the sacred entity it is, bowed down to when passed in a temple, and cared for by the rituals designed for the Deity and purpose it represents?

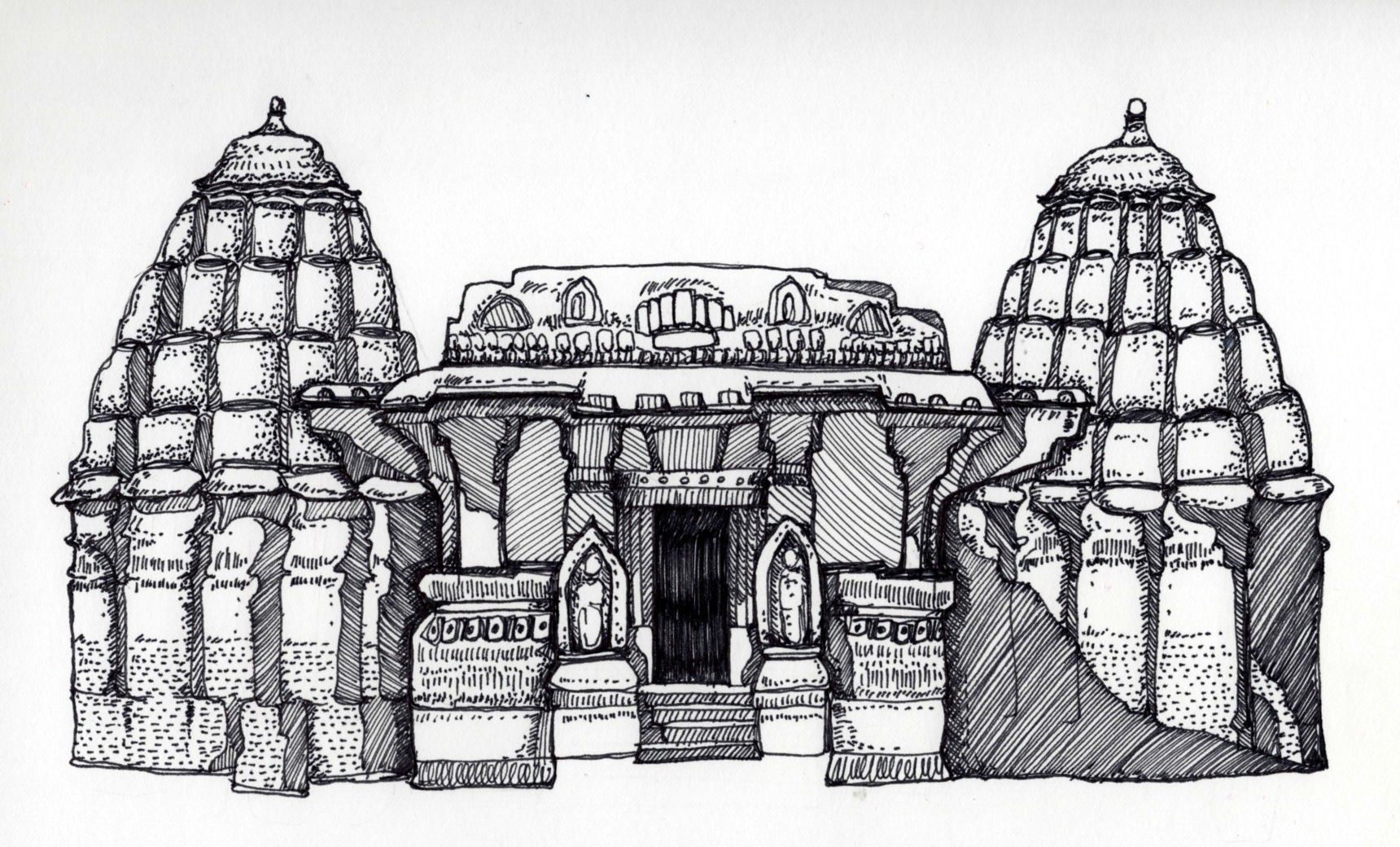

Illustration of the Somnathpura temple dating back to the 13th century Hoysala dynasty in the Somnathpura village by Mariah Joyce

What is lost when a Deity is taken out of its context, when it was so intentionally crafted for it to begin with?

Using this particular Hoysala Sarasvati as an example, the intent of the artists was to create a home for a Deity that was simultaneously a sculptural and architectural marvel. To put forth a singular piece as a representative of the whole—as often seen in the museum context—is inadequate. It loses the context and the subliminal teachings of the cultural philosophy that birthed the very artwork that is being hailed as praiseworthy. Murtis are embodiments of the Deities that they are carved for. That is, if a statue of a deity is broken, it is quite literally the breaking of that body. It is the desecration of the home of that energy, and it necessitates the carving of a new one, done with the same devotion, intention, preparation, and heart as the previous one.

To reduce this context of the murti to being just an artwork is to remove the layers of knowledge and understanding that come along with it. More importantly, it implicitly de-recognizes the legitimacy of the knowledge and thought that gave rise to this artistic creativity to begin with.

What’s more, the so-called legitimizing of the artwork through the Western canon is representative of the continued enforced hierarchical reality of Western thought and institutions in a purportedly equal global order. In providing the little information that a Western audience might ostensibly be interested in, it implies that is all there is to the context, the culture, and the work.

When narratives and categories are constantly defined and controlled by Western powers, it reinforces a historically unequal playing field. It reinforces stereotypes and false realities that were created to uphold a system that allowed one set of people to dictate who the rest of the world was, and what of their culture was globally relevant and valuable, and even socially relevant. If this feels uncomfortable or irrelevant to everyday life, a little bit of research into the real origins of Yoga and a look into how the West has bastardized it wouldn’t be amiss.

When what is considered to be art is controlled by one ideology and one intellectual perspective, the artistic traditions that once flourished become relegated to the status of local or tribal art, and “cottage industries”—thereby implying that what the Western art historians or curators call art is contrastingly global and all-inclusive. This is only compounded by many Western museums’ claim to be the protectors of the international historical canon. Who decides that canon? Whose narratives does it privilege? It is also ironic that the self-professed keepers of the historical record erase the traces of the colonial, violent origins of their collections by side-stepping the authority of the communities that birthed the artistic traditions in the first place.

The unacknowledged hypocrisy feels apparent to those of us who often look at sacred objects, statues of Deities, relics, and artistic traditions that are still very much alive in our culture but sit trapped behind the glass casing of an externally enforced label of being from a past civilization, often separate and distanced from modern and contemporary cultural representations of the human story.

India is by no means the only (even if one of the less acknowledged) countries to be embroiled within the restitution debate. Multiple African countries are similarly afflicted. Malian writer, and director of the Institute of Afro-American Affairs at NYU, Manthia Diawara wrote an open letter published on Hyperallergic to French President Emmanuel Macron entitled, “A Letter to President Macron: Reparations Before Restitution.” In it, Diawara pointed out that many sacred objects that had been stolen had been termed African artworks and had become trophies of conquests and colonization, as it was Europeans who bestowed on them a market value and symbolic capital by deeming them worthy of Western museums.

These museums—especially encyclopedic ones like the Art Institute—cite the (undeniable) educational value of their collections, and are hailed as educational centers. But it is important to question, especially in the context of repatriation and restitution today, what that education even means when the majority of these museums don’t acknowledge the unethical colonial roots, or in some worse cases illegal present-day ones, of their acquisitions.

Illustration of the artist Raja Ravi Verma’s painting, "Goddess Saraswathi" by Mariah Joyce

Museums are certainly unparalleled in the diversity of their reach. People from all over the world, and different walks of life, have the chance to be educated about culturally different practices and traditions when they are on display. However, there is also a comparably large population that sits waiting ready to welcome a murti when it goes back home.

India is not only a country of over 1 billion people when the West wants to lecture her about overpopulation.

Museums are reckoning with their colonial pasts; in the case of India, other South Asian cultures, and African cultures, colonization and museum culture are inextricably woven together. The continued and unchanging existence of such museums enforces a similar social and political hierarchy of art and culture that was once coerced onto former colonized populations. The unravelling of this can often be uncomfortable and challenge narratives that have been built over the last few hundred years about the larger geopolitical and socio-political structure and hierarchy. But in a world that’s moving forward toward intellectual pluralism, it has never been more important for museums to be transparent in their effort to provide equal and equitable intellectual and cultural spaces.

Museums are culturally important institutions. They have an undeniable potential for incredible educational value, and an ability to present different cultures in a cohesive curated space. It is evident that the world we live in is smaller than it ever has been, and an equal exchange of cultures has never been more important in times as politically polarized as the one we find ourselves in today.

The issue here is simply that museums are not centers of equal cultural exchange.

The returning, swapping, or at the very least negotiating of a shared custody, is a much-needed start of a systematic shift in thought to level what has been an unequal playing field for centuries now. These actions acknowledge the value of those traditions today as opposed to subliminally labelling them as dated practices. Alongside this, what is as necessary is the dismantling of the assumed innate superiority of Western ideology and perspective that is prevalent in institutions such as the ones in question.

While Museums like the Art Institute spend a lot of time being an encyclopedic force, it’s important to question in 2023 if a single institution can ever encompass the depth of the knowledge of the hundreds of cultures it purports to? And more importantly, if the said institution does not acknowledge the real history of colonization and the impacts it has, what narratives are being constructed, and for whose benefit? To be called encyclopedic is to be considered to have vast and complete knowledge. But what constitutes “complete?” What are you teaching those whom you have a responsibility to?

Museums need to function more as cultural experience centers. Think like the vibe of a science museum, where the eye that peruses the collection is less exoticizing and more experiential: one that sincerely considers the context, culture, philosophy and thought process that birthed the artwork. The interactive, and engaging nature of the science museum, responses to challenges of increased accountability, and increased demands for accessibility, are ones that encyclopedic museums would do well to learn from.

It is safe to say that museums as institutions are here to stay, but it is important then that we consider the historical origin of these establishments and hold them to the educational purpose they purport. It is no longer enough to issue public apologies and statements that indicate profound thought and consideration. Museums, especially ones like the Art Institute, are accountable to their audience, they are accountable to the cultures they represent, they are accountable to the people. It is 2023. Perhaps it’s time they accept that accountability and begin to create spaces where all cultures and practices are presented on equal standing.

The difficult conversations we are having today are sowing the seeds for a new museum culture, and following through on that and cultivating it must be a priority for these institutions.

In a world that is only beginning to tackle the real task of decolonization, perhaps it is time that cultural heirlooms and heritage of former colonies are returned to the contexts for which they were carved and created, or at the very least with respect to legal ownership, returned to those who understand the full significance of Who they are looking at. It is also time that the cultural contributions of these former colonies—past, present and upcoming—are held on par to those of our former colonizers, so that we may move toward a true culture of multiplicity of perspectives and knowledge.

This is an abridged version of the full essay, “The Price of Entry,” that can be found here.

Images are provided by the author

.png)

Comments