Traces of Indian Royal Names in Prakrit and Deity Names in Sanskrit in Asia Minor: Uncovering Their Historical Significance and Origins

- In History & Culture

- 03:14 PM, Nov 04, 2024

- Rupa Bhaty

The Hittite, Mitanni, Phrygians, Assyrians

The Hittite (1700-1200 BCE) archives at Boghazköy (modern-day Boğazkale, Turkey) are a remarkable collection of ancient texts that offer invaluable insights into the history, language, and culture of the Hittite civilisation, which flourished in Anatolia and Northern Syria during the second millennium BCE. Discovered at the site of Hattusa, the Hittite capital, these archives include thousands of clay tablets inscribed in cuneiform, which have preserved a wealth of information about the Hittites’ administrative, religious, and diplomatic practices. Dating primarily to the 14th and 13th centuries BCE, the texts cover a range of topics from treaties and laws to myths and rituals, revealing the Hittites as a sophisticated, well-organised society with a vast network of political alliances extending into the ancient Near East. They were sacked by Phrygians during the 12th century and ruled till the 7th century BCE.

Significantly, these archives document interactions with neighbouring powers, such as Egypt and Mitanni, through treaties and diplomatic correspondence that highlight the Hittites’ influential role in the ancient world. In the year 1350 BCE, Mitanni was powerful enough to be included in the Great Powers Club along with Egypt, the Kingdom of the Hatti, Babylonia, and Assyria. They also include rare linguistic records, such as words from Indo-European languages, making them an essential resource for studying the ancient Indian-Arya presence in Western Asia. This archive, therefore, not only illuminates the Hittites’ complex political landscape but also sheds light on cultural exchanges, linguistic influences, and the spread of Indo-European languages across the region.

There are many researchers in the early 20th century who have provided great insights on the linguistic studies of these tablets found from Tel-el-Amarna (dated mid-14th century BCE) exchanging letters. I found Pt. Lacchami Dhar Shastri Kalla is a voice to be heard on many of her valid findings which need attention today because there are still debates that arise like a Phoenix on the Mitanni to have existed from the early Vedic period. Many researchers back the hypothesis that the Vedic origins appeared near the Steppe and the old Vedic language had its origin outside the subcontinent1. But strangely they propound that Sanskrit originated in India.

In one of the articles[1] Shoaib Daniyal argues on the basis of Edwin Bryant’s book that Sanskrit originated out of India i.e. in Syria. Let's see the argument of Dr. Lacchami Dhar Kalla who wrote this fascinating book called “The Land of Arya”, and other original works on Assyrian, etc. In the book “Assyrian Personal Names” written by Knut which I would recommend every linguistic researcher to download from archives.org and reread to understand the pointer evidence. It goes against the hypothesis of the origins of Vedic Sanskrit as well as Sanskrit Out of India. However, these originals were not cited by Shoaib Daniyal for the journal where he published his half-baked findings to create headlines.

Let's look into Pt. L D Shastri Kalla’s argument on Mitanni numerical found in the Hittite archives

Pandit Lakshmi Dhar Shastri Kalla was the first head of the Department at St. Stephen's College. After completing an archaeological apprenticeship under Sir John Marshall, he joined the college as a lecturer in October 1916. An elected member of the Royal Asiatic Society, he was a scholar of multiple Indian languages, Persian, Arabic, Greek, Latin, German, French, Russian, and English. His works, The Birthplace of Kalidasa and The Homeland of Aryans earned high acclaim from scholars worldwide. Kalla (1930) et al had argued that the recent findings from the Hittite archives at Boghazköy provide a strong case for Indian-Prakrit influence in ancient Western Asia. He gives an argument for the numerical pronunciation in Hittite as,

"The recent excavations among the Hittite archives at Boghazköy-Boghas Keui have brought to light a Mitanni[2] document that deals with horse-breeding and relates the Aryan numerals thus : - aika (one), teras (three), Penza (five), Satta (seven), Nava (nine). Now Satta signifying seven, is very significant. In India we know Satta is an ancient Prakrit form for Sanskrit Sapta. Thus, the Satta-speaking people could not have invaded India from the upper Euphrates for the Indian Sapta can in no way be derived from the western Asiatic "Satta" (for 'P' would be inexplicable in Sapta, if it were derived from Satta) but satta can easily be understood as derived from Sanskrit Sapta by way of assimilation of 'p' with the contiguous' t ' in Satta, a form so familiar in the Indian Prakrit. We recognise Satta as an Indian commodity in free use among the Indian Arya(n) fighters of Mitanni on the land of Western Asia."

"For the Iranian word for seven is Hapta, (another form derived from Sapta) from which Satta cannot phonetically be derived."

His argument on the word Satta and its Prakrit nature weighs more than any other research that I have cited amongst the recent research breed. Mitanni record that discusses horse breeding also lists Aryan numerals, including words like "aika" (one), "teras" (three), "penza" (five), "satta" (seven), and "nava" (nine). Particularly, Kalla points out that the word "satta" is striking since it is an ancient Prakrit form used in India for "sapta," which means seven in Sanskrit, while I can easily cite Penza to be Prakrit Panja as in Punjab, even the readers can.

Teras comes from Sanskrit Tisra for numerical three, the elongation via the introduction of a vowel before any half consonant added with a full consonant at the end of the word is very common in Punjabi and Prakrit like Indra becomes Indara or Mahendra becomes Mohinder. He argues that this linguistic pattern supports an Indian origin for these terms, rather than a Western Asian one, because the transition from "satta" to "sapta" or even in Avestani (s>h) “hapta” from “satta” is impossible if Aryas were transiting Asia Minor to India because Iranian land will come in between to migrate to India. It's only sapta to satta which reflects common changes in Indian languages, and not an imported trait. Against the above findings by Kalla et al, when an online site like the University of Chicago's department "Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures (West Asia and North Africa)" exhibits Hittites to be older than Sanskrit it defeats the purpose of a fair and just research. It is reasonable to conclude that the Satta-speaking people were originally Indian settlers or invaders in Babylonia and were quite distinct from the Vedic period but carrying the Vedic culture as we do to this date in Vedic Yajna rituals.

The rulers of Mitanni, Yanoan, Keilah and Taanach had Indian names

Furthermore, Kalla et al correctly say that,

"The rulers of Mitanni had Indian names such as Sutarna, Tusratta etc, they signed solemn treaties and invoked the Indian gods Indra, Varuna, Mitra and Nasatya which names could not be derived from the Iranian branch of the Aryas, for the Zend equivalent of Nasatya is Naonhaitya, of Mittra is Mithra, and in the Zend, Varuna is replaced by Ahuramazda and Indra is degraded as a demon."

These Mitanni names didn't undergo any change which can be seen in considerable amount in Zend equivalents. He further says,

"The Tel-el-Amarna tablets mention Aryan princes in Syria and Palestine too, for example; Biridaswa of Yanoan[3], Suwardata of Keilah[4], Yasadata of Taanach[5]. Now Biridaswa cannot be an Iranian king for the Iranian form of Aswa is Aspa as in Vistaspa. Biridaswa is distinctly an Indian name Vrihadaswa so familiar to the Indian tradition- Biridaswa being the Prakrit form of the Sanskrit Vṛhat."

Here I would add that we have the pure Sanskrit name Bṛhadaśva in Vedic text, but this won’t make them Vedic since the Rgvedic names like Trita (eg. Author Trita Parsi is an Iranian-born Swedish writer and activist), or Tṛtus (Tṛtus Reakcje of Estonia) are still prevalent and in vogue amongst people of Asia Minor. This can suggest only one thing, the people during the Bronze Age did use the Rgvedic names for themselves of which few had the Prakrit influence and few remained as it is. It also shows that IVC had a mixed breed of people, those people who went abroad and spread during Vedic times and came back, and those who were purely inhabitants of India. They still had interaction and trade connections. Therefore, we find both kinds of names prevalent in India as well as in Asia Minor. I researched through the names of Kalla et al in the original text by Knut who says in his book’s introduction-

"It is worthy of special mention that he was the first to suggest the possibility that the name of the Palestinian prince Su(v)ardata contains the Skr. word svar (Av. hvara) "sun"- and thus represents a period of linguistic development when the Iranian sound change "s >h" had not yet taken place.”

In my opinion, Kalla is spot-on in his argument. The Palestinian Prince name has not been an Iranian product and his finding indirectly endorses Knut here. Knut further writes,

"Apart from the already mentioned names Nasattiia and Suvardata, the following also appear to me to be purely Indian in type: Artaššumara (Ind. Artasmara* "remembering the law"), Biridašva (Ind. prd-ashva*11), Iašdata (Ind. n. p.Yasho-datta), Ruzman^a (Ind. rucimanya*), šatiia (Ind. n, p. Satya "the faithful one"; Avestan. haipya, Old Persian. hašiya), šauššatar (Sau-kṣatra, patron, of Ind. n. p. Su-kṣatra, Avestan. huxšahš,ra),=Subandi (Ind. n. p. Subandhu), Suta (cf. Ind. suta), Sut(t]arna (perhapssu-tarana, SCHEFTELOWITZ), Sutatana (possibly=suta-tana "to whom offspring has been born", or =sūta-tana "son of a charioteer", cf. Ind. n. p. Sūtatanaya), Tu(i)šratta (cf. Ind. tuviṣ "strong, big",and ratha “chariot")."

Professor Winckler, in 1910, supported the theory and expressly maintained that the Tell el Amarna and Boghazkoi texts, have to do with real Aryans before their division into Indians and Persians. He shows that the ruling class in Mitanni was called Harri, a name which survives in the second column of the Behistun inscription, where it denotes the Aryans, and, further, that the persons in closest touch with the Mitanni kings, namely, the nobility, are named marianni, which seems to be identical with the Vedic word marya,"man, hero". It appears to me that Harri can refer to Hari-kula of Yadu Vaṃśa-lost lineage although right now this theory in making is far-fetched.

But I assert on Kalla et al’s findings that the Mitanni used Prakrit names for themselves while the Vedic deities are of course from the post Vedic times. Avesta has separated long back and has some frozen archaic information like Indra’s decline which can be felt in the Rgveda itself. On the contrary, we read that Kassites have their deity named Indas which was either not yet demonised or could have been propagated by the later Prakrit People following Vedic deities.

Indian king name Ambaris in Tabal

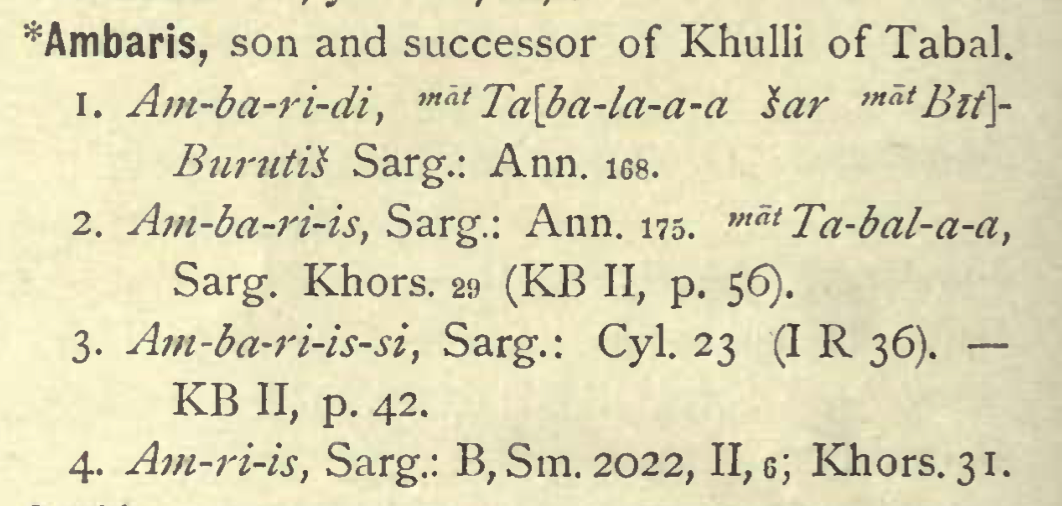

Down the lane, we come to 7-8th century BCE from Mitanni’s times of 15th -19th century BCE. Now we come across a prince name Ambaris ([m]am-ba-ri-is); Amris ([m]am-ri-is); Amriš ([m]am-ri-iš), much later to Hittites. A similar name is borne by the Ikṣvāku kings from Rgvedic times. This name can have a Sanskrit variant Amri by the rules of Prakrit (cf Amrapali). In the pic from Knut's book on Assyrian personal names, one can see the Prakrit influences and variants in different words of the same name Ambaris.

Screenshot from Knut's

However, let's see the Assyrian part of Ambaris. Atuna is a kingdom in Tabal mentioned in royal inscriptions of the Assyrian kings Tiglath-pileser III (r. 744-727 BC) and Sargon II (r. 721-705 BC).” Hulli, “nobody’s son”, held the land of Tabal on behalf of the Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser (Hawkins 1979 161; Aro 1998c 130). He had replaced the rebel Wassurme/Wasusarmas (Jasink 1995 132, 178)(PDF) Lydians in Tabal (1°).

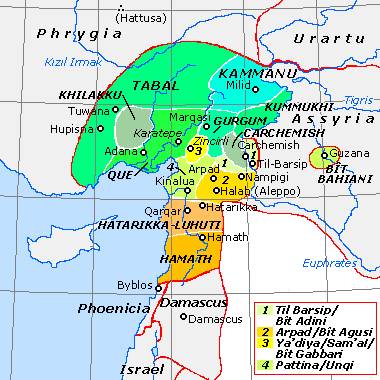

Phrygia, Kingdom of Tabal, Phoenicia and Assyria

Interestingly, the word Wasusarmas is more affiliated with Sanskrit instead of Avesta or Assyrian language and can be called Vasu-Sarma without any doubt. Ambaris was the son of Hulli/Khulli (Knut et al) and son-in-law of the king of Atuna, who received Sinuhtu from the hands of Sargon II in 718 and took over Bit-Purutaš in 709 BCE. Hulli/Khulli remembered as "nobody's son" indicates his unknown whereabouts leaving a blank for the historians who are still speculating to locate his origins.

With a linguistic approach, the origins of Wasusarmas (who were defeated by Ambaris) and Ambaris can be none other than Indian origins. It appears that some pockets of Asia Minor were still inhabited by Indians who were continuously habitating in Asia Minor taking with them the original Vedic names from India which were still in vogue till the Neo Assyrian or even later times which is unknown to us.

Dr. Bork* has shown that an 'h' has disappeared in the Mitannian. He is confirmed in this by the fact that the 'h', which occurs (conventionally preserved) in Lycian inscriptions, has nothing corresponding to it in Hittite names (cf. under the elements amba, ambar, anda, indi, ru), and is not even indicated in Grecian transcription of names from Asia Minor. This also reinforces the Indian influences with possible lands belonging to India and its extended satrapy across Asia Minor probably were consistent from Vedic times.

"Names of Indo-Aryan deities (Vedic) are also found among the Kassities, who established a royal dynasty at Babylon about 1760 B.C such as Suria (Indian Surya) Maruttas (Indian Marutas) Bugus, (Indian Bhaga) Indas (Indian Indra). The Kassites also retain the memory of the Himalayas as Simalia," says Kalla et al.

He endorses that the Kassite deity Indas cannot be derived from Avesta Indara. I found that the word Indas comes directly from the root Inda for the deity Indra, which means “to drop". Moreover, he says the Babylonian name for horse 'Susu' is said to have derived from the Aryan 'Asva' as it cannot be derived from the Iranian 'Aspa'.

Indian Toponyms in Asia Minor and Asia with some Anthropological impacts

Apart from Waššukanni/u₂-šu-ka-ni[6] (Vasukanni) possibly came from Sanskrit Vasukarṇī, a capital of Mitanni the word which originated from Maitanni[7] which was the earliest recorded form. It is supposed to be composed of a Hurrian suffix -nni added to the Indo-Aryan stem maita-, meaning "to unite" and comparable with the Sanskrit verb mith (मिथ्; lit. 'to unite, pair, couple, meet’) but to me it appears to be possibly derived from Maitraṇi (Sanskrit)-Maitanni (Prakrit) culminating to Mitanni, both the names are Indian and Sanskrit-based.

When we look upon the word Bit-Purutaš/Porotta, Angelo Papi et al speculate that this may ultimately be derived from the Hittite purut- “clay.” (Tischler (1977-2016 II 11/12 668-670), s.v. purut-.) This would confirm the Lydian origin of Purutaš, which probably referred to a “mass of buildings made of mud bricks”. I would like to bring the reader's attention to the Vedic "Pur"- which also means the dam/fort/city which was made of mud and later bricks.

Influence of Indian Prakrit Names in Asia Minor

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

There are other Toponyms are of utmost importance to look upon. Some hints we get from the name of places like Gargamis (possibly Gargas) Knut et al (pg XXXI), Phrygia (Bhṛgu). Herodotus says that the Phrygians were called Bryges when they lived in Europe, which can be none other than Bhṛgus. The presence of Bhṛgu is well documented from the late Bronze Age and is associated with Metallurgy. They are called the sea people and once were the reason for the downfall of Hittites.

One can easily connect with why Persians knew Bhṛgukutch or Barygaza when they got themselves deported from Iran due to the Islamic invasion and their quest in Persia. If in the word Bhṛgukutch, the ‘Kutch-Kaccha’ depicts ‘gaza’ in Barygaza then the Ancient Greek Gáza, the Biblical Hebrew Ġazzā may be the Prakrit form of ancient Sanskrit word Kacchapa or Kashyapa.

Apart from Tel-el-Amarna tablets I have found an interesting etymological connection of the name Palestine in Sanskrit texts which is unavoidable. Its original ancient name is Palastu[8] which sounds similar to Sanskrit Palasti, Pulasti and Pulastya. Its origin is palaistês, the Greek noun meaning “wrestler/rival/adversary”( Noth 1936). 717 BCE: Sargon II's Prism A: records the region as Palashtu (Hallo & Younger 1997, p. 2.118i).

Initially, I believed them to be Homophonic words. If we look in Sanskrit we find a Vedic word Palasti, which means grey hair of head and arms used for Bhargavas who would grow old sooner than the Jamadagnis and the second one is Pulasti which means wearing the hair plain and the third is Pulastya, one of the Saptaṛṣis, and one of the Ten Prajāpatis, which may have created a tribe in ancient times or had multiple migrations during Late Vedic times. The name Palastu can be a very ancient name of the place which continued in the Bible also. It may have been since we know that Phrygians were Bhṛgus-Bhargavas and the Palasti word endorses it. Where would you find such uncanny homophones, I can surely say India. It thus appears that the land of Phrygian and Palestine belonged to Bhṛgus. The Topnymns remained, but the cultures changed. Interestingly we find the documented name Ahiram (Sanskrit Ahir-cowherd shepherds-Yadus) as the king name of Phoenicians which many researchers have equated with Rgvedic Pāṇīs. Pāṇīs were also anti-Indra and Historical Krishna in his times declined the oblations to Indra. There are a few interesting connections but yet to be delved deeply into.

Let’s understand Asia from the Akkadian dynasty. Asia Minor, located in the southwestern part of Asia, mostly covers modern-day Turkey. The first recorded mention of the area is from the Akkadian Dynasty (2334–2083 BCE), where it was called "The Land of the Hatti" and was inhabited by the Hittites. This region was very important in ancient times. The Hittites called the area "Assuwa", which originally referred only to the area around the Cayster River delta but later came to mean the entire region.

"Assuwa" is thought to be the origin of the name "Asia," which the Romans later used for this area. The Greeks called it "Anatolia," meaning "place of the rising sun," referring to lands east of Greece. The Hittites called the area "Assuwa" which was earlier known as "Aswiya," which in the pure Sanskrit word Aśvīya means "land favourable for horses" or a sheer and unavoidable cognate of Aśvīya which would mean people conducive to horses which brings light upon the places inhabited by Rgvedic “Aśvapatis”.

Many researchers have equated Caucaasus to have been “Kaikaya”. The modern names of the Caucasus originate from the Greek “Kaukasos” which sounds more like the land of “Kaikayasya”. Greeks remember it as the land of the rising sun in the east. One of the Vedic names of Sun is Aśva which is completely unavoidable in the case of etymology of Asia.

Now let's glean into the word Hatti. Hatti, if it is a Prakrit word then by reverse engineering it could have come from the Sanskrit word Hasti, which would mean Elephants. It would mean that the Land of Hatti was inhabited by Indians. Then, they should have brought elephants with them from nearby land as well as India.

Archaeology[9] tells us that the land of Hasti (elephants) was indeed inhabited by Indian and Syrian elephants, or the people from India were called upon to tame the elephants during the Bronze Age and we are yet to find a Kikkuli (manual of horse training) type of cuneiform manual for elephants. The paper says,

There are several discussions about the origin of the southwest Asian elephants. Some researchers support the idea that the elephants were not endemic and arrived there as live animals and/or as raw material from the Indian subcontinent, traded or sent as tribute (e.g., Arbuckle and Erek, 2010; Vila, 2010). On the other hand, some researchers put forward the idea that a population of Asian elephants inhabited the Euphrates-Tigris River Basin in the late Holocene (e.g., Becker, 2005, 2008; Miller, 1986). Although there are genetic data from the elephants from Gavur Lake Swamp (Girdland-Flink et al., 2018), they cannot distinguish between the natural and anthropogenic origin of the population in the Middle East during the Bronze Age (3000-1200 BC). Nonetheless, morphological data and the absence of cut marks or any other associated archaeological evidence may be a sign of the natural presence of the large population in Gavur Lake Swamp (Albayrak and Lister, 2012; Girdland-Flink et al. 2018).

However, Turkey had a natural presence of a large population of elephants during the Bronze Age. Just like Hatti, Hasti of Turkey area also had names like Hastinapur. In Sanskrit, Hastinapura translates to 'the City of Elephants' from Hastina (elephant) and pura (city). Similar to Southern India’s Andhra which has Hasti surnames, a northwestern state like Gujarat has Prakrit Hathi surnames.

Linguistically speaking

Does the land of Hittites, a country in Asia Minor, bear the oldest Indo-European Language? Such questions emerge constantly. This very question also needs to be addressed. Research at the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures online site says that,

"Studying Hittite language and culture brings to light some of the foundations of our modern Western civilisation. Hittite is the oldest Indo-European language known—older than Greek, Latin, or Sanskrit. "As an Indo-European language, Hittite is related to modern-day languages like English: the Hittite word for “water” is watar! But it is not always that transparent. English “who” is kwis in Hittite."

Now let's understand these two key words which are found in this research "Why study the Hittites?" One is the Hittite word for “water” which is pronounced watar! It has directly originated from the Sanskrit word "udra" which is formulated in the from Proto-Indo-European *ud-ró-s (otter-aquatic animal), which comes from *wed- (“water”) (ref. From Middle English wateren, from Old English wæterian, from Proto-Germanic *watrōną, *watrijaną, from Proto-Germanic *watōr (“water”), from Proto-Indo-European*wódr̥ (“water”) here.

Let's take the second word from the research article, i.e. English “who” is kwis in Hittite, for which English etymology is uncertain. Let's see what the etymology of "Who" tells us. From Middle English who, hwo, huo, wha, hwoa, hwa, from Old English hwā (dative hwām, genitive hwæs), from Proto-West Germanic *hwaʀ, from Proto-Germanic*hwaz, from Proto-Indo-European *kʷos, *kʷis. So, for the PIE kʷís they constructed the root directly from the Hittite word kwis. Likewise "watar", the Hittite word "kwis"(from Hittite: (ku-wa-pí) for "who" can only come from "कः - kaḥ" Sanskrit कृ - kṛ and Prakrit/Marathi kā won't even require a PIE mediation.

Moreover, a recent migration of Romani (Roma) from Rajasthan via north-west Punjab into Europe in around 250 BC-500AD gives us a pattern. A local language that they used to speak in the Sindh-Rajasthan area created new sounds in the original words in the language in vogue, which is the Domari language. A sister split occurred to create a new deformed sounding words which sounded like the already migrated words during Bronze Age. See the numerical names of Romas and compare with Domari and others.

Roma - ekh (1), jekh (1), duj (2), trin (3), štar (4), pandž (5), šov (6), ifta (7), oxto (8), inja (9), deš (10), biš (20) and šel (100).

Domari - yika (1), dī (2), tærən (3), štar (4), pandž (5), šaš (6), xaut (7), xaišt (8), na (9), des (10), wīs (20) and saj (100)

Sanskrit - éka (1), dvá (2), trí (3), catvā́raḥ (4), páñca (5), ṣáṭ (6), saptá (7), aṣṭá (8), náva (9), dáśa (10), viṃśatí (20) and śatá (100)

When a recent migration can change the sounds in language, one can explicitly understand what could have happened during the Bronze Age and earlier ages when the migrated people tried to fuse their language with an already existing regional language. Thus, when Prakrit was officially accepted as a language in India in the past, its impact can easily be cited in Asia Minor, as documented by Kalla et al.

Takeaways

In his pioneering role at St. Stephen’s College, Pandit Lakshmi Dhar Shastri Kalla championed the study of linguistic and cultural exchanges between ancient India and Western Asia. Through his archaeological findings and analyses, Kalla argued for the deep influence of Prakrit in the names and of Sanskrit on Mitanni deities. The Kassite deity Indas, lacking Avestan traits and viewed as a demon in the Avesta, highlights distinct Indian influences, suggesting that Mitanni operated as a satellite state of a broader “Greater India.” Kalla’s findings imply that Indian cultural reach extended deeply into regions like present-day Palestine, Israel, Turkey and surrounding areas, indicating a notable Indian presence in Asia Minor.

I highlighted the name of Prince Ambaris and analysed his connection and revolt to Vasu-sarama, a figure appearing later than the late Bronze Age, to suggest that the region was continuously inhabited by people of Indian origin and had been consistent, perhaps through migration or settlement or invasion, and was longstanding in Asia Minor from the early Assyrian period.

I argued that the Hittites language is younger than classical Sanskrit with the help of citation of Proto-Indo European (PIE) roots where English/old English doesn't bear the origins while Sanskrit roots do.

The term "Asia," believed to have originated from *Assuwiya (Assuwa > *Assuwiya > *Asswiya), can be explained through Sanskrit, which strongly suggests Indian influence on Asia Minor rather than the other way around. The Sanskrit root and etymology likely underpin the formation and spread of this term showing the explicit influence of India on Asia Minor and not vice versa.

The influence of Sanskrit and Prakrit in place names across Asia Minor suggests a clear Indian cultural impact, implying that the Vedic period predates the Bronze Age. Evidence points to the spread of Indian linguistic and cultural elements into Central Asia (Avesta region) and Asia Minor during a post-Vedic era. However, this influence was selective, with pockets retaining distinctly Indian-origin words and names without Avestan influence, indicating that Avesta did not serve as a cultural bridge between the Indian subcontinent and Indian-settled regions in Asia Minor.

While Avesta emerged as a parallel tradition to the Vedas as an offshoot of Vedas, regions in Asia Minor retained Vedic deities and cultural elements closely aligned with those in mainland India, preserving the original character of these deities without adopting the Avesta's interpretations or modifications. This continuity underscores Asia Minor's strong connection to Vedic traditions, independent of Avestan influence, and hints at sustained cultural transmission directly from India to these regions continuously through the times when Prakrit language also was in vogue.

These are a few fragmentary memories in the form of princes/kings names and a few toponyms retained due to few documentations available to us in the form of Tel-el-Amarna tablets letters. There may have been many others.

References

1. World History Encyclopedia (an online portal)

2. Kalla, Pt. Lacchami. Dhar. (1930) The Home of the Aryas. The Delhi University Publications.

3. KNUT L. TALLQVIST, ASSYRIAN PERSONAL NAMES, ACTA SOCIETATIS SCIENTIARUM FENNIC^E. TOM. XLIII, No. i. (HELSINGFORS 1914)

4. scroll.in ; The Old Vedic language had its origin outside the subcontinent. But not Sanskrit

5. scroll.in ; India wasn't the first place Sanskrit was recorded – it was Syria

6. (PDF) Lydians in Tabal (1°). Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376595601_Lydians_in_Tabal_1[accessed Oct 30 2024].

7. (PDF) Ambaris, alias Abbaites, a Mysian son of nobody. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380168188_Ambaris_alias_Abbaites_a_Mysian_son_of_nobody

[1] Scroll; India wasn't the first place Sanskrit was recorded – it was Syria

[2] Mitanni (c. 1550–1260 BCE), also known as Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian records around 1600 BCE, Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat in Assyrian records, and Naharin in Egyptian texts, was a Hurrian-speaking kingdom in northern Syria and southeastern Anatolia (now Turkey) with notable Indo-Aryan influences in language and politics. Source-Wikipedia

[3] Yenoan-Yenoam or Yanoam (Ancient Egyptian: ynwꜥmꜣ) is a place in ancient Canaan, or in Syria, known from ancient Egyptian regnal sources from the time of Thutmose III to Ramesses III.[2] One such source is a stela of Seti Ifound in Beit She'an. Another is the Merneptah Stele.

[4] KEILAH (Heb. קְעִילָה), city of Judah, in the fourth district of the kingdom, together with Achzib and Mareshah (Josh. 15:44; cf. I Chron. 4:19). It is first mentioned in the *el-Amarna letters, in connection with disputes between the king of Jerusalem and the kings of the Shephelah (nos. 279, 280, 287, 289, 290).

[5] Tell Taanach, situated close to Megiddo in the Jezre’el Valley, in Israel, and is close to the biblical city of Ta'anach, which is now represented by the Palestinian village of Ti'inik:

[6] Text Corpus of Middle Assyrian. Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus. Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

[7] Wallis Budge, E. A. (1920)An Egyptian hieroglyphic dictionary: with an index of English words, king list and geological list with indexes, list of hieroglyphic characters, Coptic and Semitic alphabets, etc. Vol II. John Murray. p. 999

[8] (and Akkadian (Pilistu), (Palastu).

[9] Ebru Albayrak; The ancient Asian elephant of Turkey in the light of new specimens: Does it have regional features? July 2019

Image source: Swarajya

Comments