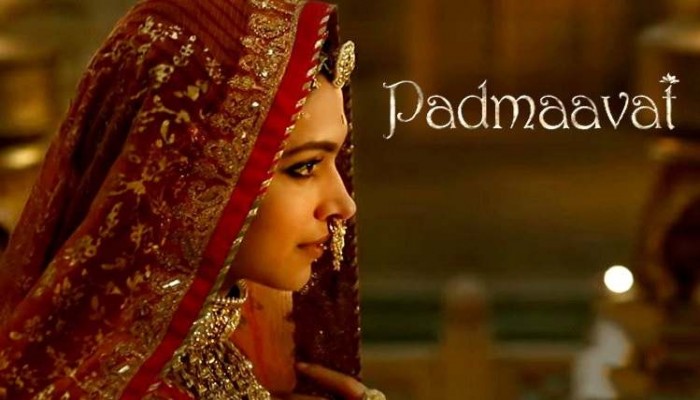

The Tragic Reality of Representing Trauma through Art- How Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Padmaavat failed us

- In History & Culture

- 05:14 AM, Jan 29, 2018

- Rajat Mitra

The other day, my wife and I had gone to the nearby mall to buy some essential items. As we sat down to eat, we noticed that in the hall near us, the show of ‘Padmavat’ had ended. The audience had started to trickle out and soon became a crowd, jostling, pushing and elbowing, cracking jokes.

There was a feeling of excitement on the faces of most people. Many of them looked as if they had been injected with a dose of adrenalin.

“Don’t they all seem to be on a high?” I asked myself.

As some of them now sat around us discussing the film, I couldn’t help but overhear the remarks. I have outlined some of the most frequently heard ones.

“Solid entertainment for three hours.”

“Koi aisa scene hi nahi tha. Faltu ki controversy banadi gai.”

“Kya acting thi Khilji ki. Ranveer Singh toh chha gaya tha. Deepika bhi.”

“Ratan Singh to gazab ka lag rah tha. Aur do teen dance hone chahiye the.”

“Bhansali ne kya sets lagaye hai. Ghoomar dance solid tha. Jauhar bahut cinematic dikhaya hai. Only Bhansali can do it.”

All the comments were on the personal appearances of the actors, on the huge sets and scenes and lastly on the dialogues. The adulation around Ranveer Singh, the one who played villain as Khilji, seemed similar to Gabbar Singh, the dacoit of the movie Sholay whose dialogues went on to become a hit and whose character became larger than life.

I asked the man sitting with his family next to me how did they find the movie. “Poora paisa vasool. Jabardast excitement thi hall mein. Entertainment wali picture hai. Ek bhi controversy wali cheez nahi thi,” he told me.

The place had filled up with the people who had come out of watching the film. There was no one who looked affected or shaken. Everyone seemed to be on high praising either Deepika’s beauty or Ranbir Singh’s mannerisms. If the cross section of people I was seeing at the city mall was any indicative of audience satisfaction, then I must say the movie had truly been an entertainer.

As I surmised from the comments, entertainment and not projecting the grief, the trauma of a whole society was the central message of the movie. Scene after scene, the focus was on garish and loud sets and songs and the audience had felt captivated by it all.

As I listened to the voices that didn’t stop raving, my mind went back to another moment twenty five years ago. In Europe, I had come out with my friends after watching Schindler’s list. We all walked past silently in the cold night glad to be out and breathing fresh air. Similar to us people had walked past silently, a solemn expression on their face.

Some of the responses I remember were:

“Very painful.”

“Became aware of Europe’s history. Will never let it happen again.”

“Understand how terrible it was for the Jews and his bravery in saving them.”

“How could people be so cruel?”

Many people looked downcast and walked. It seemed they avoided all eye contact. No one seemed as if they are on a high after seeing the movie.

Two different times. Two different movies. Two different people. Yet one thing stands out as a stark reality. The two moments that I witnessed at a gap of twenty years have an uncanny similarity. One was a movie on a theme where hundreds of Jews were murdered in gas chambers while the other was where hundreds of women committed suicide to prevent being taken as slaves. Both were shown through art forms of cinematic medium and portray a traumatic event. Yet they both seemed to have ended up transmitting two entirely different messages of a wound that is historical that has not healed.

As Claude Lanzman in his “Obscenity of understanding” says, “The real issue for true art is not to just entertain but to transmit its role as an agent of truth to bridge the gap between what is knowable and what is unknowable in human understanding. What is at stake here is art itself and the way it changes the little knowledge that existed before its own creation and the knowledge it brings about human condition and truth.”

Many years ago I was at a conference in a US university. The speaker was Cornel West, a highly eminent scholar and he was speaking on race relations in USA. In the middle of the lecture, he had asked us what was the most visible symbol of American art and someone had mentioned the movie ‘Gone with the wind’. Turning to us he had pointed out how that movie whitewashed slavery and racial discriminations for an entire generation and made it impossible to view the trauma of Blacks that led to the civil war. The cinematic effects, the relationship of Scarlet and Rhett had eclipsed the horror that was slavery for millions.

Nearer home, I often wonder why we as a society, as people, disown our trauma? Why do we write, project it in a language that fails to be sensitive and disrespectful to the survivors? Why do we forget that they uphold our deepest human values? Will someone write or project it for us if we ourselves don’t do it in depth and show our denial and don’t value the introspection? If we trivialize our stories of grief and suffering by showing them through garish songs and dance, are we not seeing to it our own stories are lost? Then does it not get lost in time disconnecting us from our roots and to future generations who may need those stories to define their identity? As a friend of mine, a historian, told me while discussing this issue that what few people care to understand is that for a Rajput, it is just traumatic to think of Rani Padmini and the movie is forcing him to do just that, both as an individual and collectively as part of a race. To me this is understandable.

When an artist uses art to depict and bring out trauma of a people, unknowingly the artist not only engages and illuminates social reality of the present but also builds a provocative relationship with his own people forcing them to recreate the original trauma that may never have healed. It is a fact that artists like Spielberg have spoken about passionately for those who work with issues of war, trauma and genocide so that they don’t open the raw wounds of a society.

Where the difference lies is that some of our directors need to know that human trauma is often sublime and can only be understood through subtle and deeper emotions, not grotesque expressions whether by a survivor or perpetrator. They need to understand for themselves that representing trauma in art requires us to understand certain sensitive aspects that do not belong to Bollywood’s zeal to see itself as an unrivalled medium of mass entertainment.

As trauma researcher Caruth has pointed out, in each enactment and representation of trauma whether in film or literature, the voice of trauma comes out from the original wound itself and tries to tell the world about the injustice done by the perpetrator. When one doesn’t see that message reaching out to the audience after the creation of the artwork, one knows that the attempt by the creator has failed.

The history of Indian society is mired and woven with traumatic incidents that have stayed as a fragmented memory in our collective through stories, songs and narratives, passed on by generation to generation. There is now an attempt by writers, poets and filmmakers to portray it through their art without many of them caring to understand the experience of the very people who went through it or even the issues that tried to destroy the existence of a race. When the very people were confronted with insurmountable odds and faced it with silence and fortitude, it has to be shown with dignity and sensitivity and not through swan like movements. The invasions, the iconoclasm and conversion, the slavery and its humiliation have left a wound that has yet to heal and one has to find a language to show it. Therefore, it is perhaps needed, more than ever that art and artists today through literature and cinema play a role to give a healing touch to people.

I believe that today we need artists and intellectuals who understand this complex relationship between art and trauma. That we must see trauma and its representation as something sublime that cannot be trivialized and portrayed as a form of entertainment. At present, with artists who don’t bother to understand the language of trauma, it may seem like a farfetched dream. We need intellectuals who don’t subvert the legitimate aspirations of a people whose ancestors left them with a story that is tragic and poignant as their identity. Saying this, one can’t hide behind the cloak of ‘freedom of expression’ to express what passes as their own inner fantasy and subverts the true nature of traumatic representation of reality. I fear that if we fail in that aspiration we may unknowingly create another wound for the future generations that comes from the tragic realism of falsely representing trauma through an art that is neither true nor legitimate.

Comments