The Proto-Indo-European (PIE) Language Theory is a Linguistic Fact

- In History & Culture

- 08:03 AM, Jul 09, 2018

- Shrikant Talageri

There is no question of not being able to pin down any "foundations" for the PIE "theory", because it is not a theory at all but a linguistic fact. Instead of accepting facts, it would be a fruitless waste of time and energy to reject facts based on nothing but wishful thinking or an "I don't like this idea so I'm going to refuse to believe it" kind of logic. There is nothing more clear in the field of linguistics than the concept of the IE family of languages. I don't know exactly what is in the idea of IE or PIE that people object to:

A. Is it the basic idea that there is an IE language family distinct from other language families (e.g. Dravidian)?

B. Is it the idea that the original ancestral language was something other than the Vedic language?

C. Is it the fact that PIE is artificially reconstructed and therefore considered pure speculation?

A.

1. To begin with, compare the closest relationship words for

English: father, mother, brother, sister, son, daughter

with Sanskrit: pitar, mātar, bhrātar, svasar, sūnu, duhitar

and Persian: pidar, mādar, birādar, khvahar, pesar, (hūnu in Avestan), dukhtar.

Tamil: tandai, tāy, aṇṇan/tambi, akkāḷ/tangi, peyan, peṇ.

2. Compare Sanskrit "dvā, tri, catur, panca" with Russian "dva, tri, cetuire, pyac";

or Sanskrit "saptan, aṣṭan, navan, daśan" with Latin "septem, octo, novem, decem".

Compare the Persian numerals "yak, du, si, chahar, panj, shish, haft, hasht, nuh, dah"

with Hindi "ek, do, tīn, chār, pānc, che, sāt, āṭh, nau, das",

And then compare Tamil "onṛu, iranḍu, mūnṛu, nāngu, aindu, āṛu, ēzhu, eṭṭu, onbadu, pattu"

or Telugu "okaṭi, renḍu, mūḍu, nālugu, ayidu, āru, ēḍu, enimidi, tommidi, padi".

Compare for example Sanskrit tri, Avestan thri, English three, Latin treis, Greek treis, Russian tri, German drei, Lithuanian trys, etc. Compare all these words with Tamil mūnṛu, Malayalam mūnnu, Telugu mūḍu, Kannada mūru, Tulu mūji.

The above were just a few examples: the same is the case with body parts, names of animals, and many other common nouns, adjectives and even adverbs. Words like relation words and numerals can be borrowed from one language into another (e.g. the English words "mummy, daddy, uncle, aunty", and English numerals, are freely used in totally unrelated languages). But certain words simply cannot be borrowed, for example personal pronouns:

3. Compare the nominative plurals in Sanskrit vay-, yūy-, te, English we, you, they, and Avestan vae, yūz, dī,

or the accusative forms of the same plural pronouns, Sanskrit nas, vas, Avestan noh, voh, Russian nas, vas, and the Latin nominative forms nos, vos,

or the Sanskrit dative forms -me and -te with Avestan me and te, English me and thee, Greek me and se (te in Doric Greek), Latin me and te, etc.

The Tamil equivalents of "we, you, they" are: nāmgaḷ, nīmgaḷ , avargaḷ. And of "me, thee" are yennai, unnai.

Or Sanskrit tu- (Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, etc. tū), Avestan tū (Persian, Pashto, Kurdish tu), Latin tū (Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Romanian, Catalan tu), Irish tu (Scots-Gaelic thu, Welsh ti), Old English thū (later English thou, Icelandic thu, German, Norwegian, Danish, Swedish du), Old Church Slavic ty (Russian, Belorussian, Czech, Slovak, Ukrainian ty, Bulgarian, Serbian, Croatian, Slovenian, Macedonian, Bosnian ti), Armenian du, Albanian ti, Doric Greek tu, Lithuanian and Latvian tu, Tocharian tu.

Compare this flood of Indo-European words with the Dravidian equivalents: Tamil, Malayalam, Toda, Kota, Brahui nī, Kurukh nīn, Kannada nīnu, Kolami, Naiki nīv, Telugu nīvu.

4. Or take the basic forms of the verb, in particular of the most basic verb of all, "to be": the present tense singular conjugational forms of this verb, in English: (I) am, (thou) art, (he/she/it) is. The forms in a main representative language from each of the twelve different branches are:

Sanskrit: asmi, asi, asti.

Avestan: ahmī, ahī, astī.

Homeric Greek: eimi, essi, esti.

Latin: sum, es, est.

Gothic: em, ert, est.

Hittite: ēšmi, ēšši, ēšzi.

Old Irish: am, at, is.

Russian: esmy, esi, esty.

Lithuanian: esmi, esi, esti.

Albanian: jam, je, ishtë.

Armenian: em, es, ê.

Tocharian: -am, -at, -aṣ.

See the comparative forms in the Dravidian languages of South India:

Tamil: irukkiŗēn, irukkiŗāy, irukkiŗān/irukkiŗāḷ/irukkiŗadu.

Kannada: iddēne, iddi, iddāne/iddāḷe/ide.

Telugu: unnānu, unnāvu, unnāḍu/unnadi/unnadi.

One could go on and on giving lists of words, verbal roots, prefixes and suffixes used in the formation of words, etc.

Moreover, it is not a question of an ancient Sanskrit civilizing language triumphantly moving all over the world contributing words to different unrelated languages. Some words simply cannot be "borrowed". I defy anyone to produce a single language in the world which has borrowed personal pronouns or basic verbal forms from an unrelated language, however much it may have borrowed other words. Check again:

Sanskrit: asmi, asi, asti.

Avestan: ahmī, ahī, astī.

Homeric Greek: eimi, essi, esti.

Hittite: ēšmi, ēšši, ēšzi.

Russian: esmy, esi, esty.

Lithuanian: esmi, esi, esti.

Tamil: irukkiŗēn, irukkiŗāy, irukkiŗān/irukkiŗāḷ/irukkiŗadu.

Kannada: iddēne, iddi, iddāne/iddāḷe/ide.

Telugu: unnānu, unnāvu, unnāḍu/unnadi/unnadi.

Marathi: āhe, āhes, āhe.

Konkani: āssa, āssa, āssa.

Hindi: hũ, hai, hai.

Gujarati: chũ, che, che.

See how even the modern North Indian ("Aryan" language) words are not exactly like the Sanskrit words or like each other, though the connection can be seen or analyzed; but the words in the ancient Indo-European languages given above are almost replicas of each other, like the dialectal forms of a single language. And this is not only with ancient Greek Avestan and Hittite, but even modern Russian and Lithuanian. But all these languages have evolved separately from each other for thousands of years in different geographical areas with very little historical contacts (and certainly no known historical contacts where the interaction was so total and all-powerful that even such basic words could have been borrowed from one to the other, when there is not a single known example anywhere in the whole world where even closely situated languages with one language totally influencing the other one has resulted in the borrowing of personal pronouns or basic verbal forms).

Obviously the "Indo-European" languages are closely related to each other. But the speakers of the languages are clearly not racially or genetically related to each other (while the speakers of different language families in India are racially and genetically related to each other). So this means that these languages have spread from some one particular area to all the other areas in prehistoric times, and (by elite dominance or whatever means) language replacement took place where the people in the other areas, over the centuries, slowly adopted these languages: there can be no alternative explanation. The only question is: from which area? I have shown that it was from North India.

B. Even within Sanskrit, there is a very great difference between Vedic Sanskrit and Classical Sanskrit. It is along story, but I will give my favorite example:

1. The common Rigvedic word for "night" is nakt, found throughout the Rigveda. It is common to almost all the other branches: Greek nox (Modern Greek nychta), Latin noctis (French nuit, Spanish noche), Hittite nekuz, Tocharian nekciye, German nacht, Irish anocht, Russian noc', Lithuanian naktis, Albanian natë, etc. This word represents the earliest "Proto-Indo-European" era when all the 12 Indo-European brancheswere in and around northwestern India.

2. A less common word for "night" throughout the Rigveda is kṣap. It is found in the Avesta (where the word related to nakt- is completely missing except in a phrase upa-naxturusu, "bordering on the night") as xšap: modern Persian shab (as used in Urdu, and in the phrase shab-nam "night-moisture= dew"). This word represents the "Indo-Iranian" (mature Harappan) era when all the other branches except Iranian had moved out of the Indian horizon.

3. The common Sanskrit word, which appears for the first time only a few times in the latest parts of the Rigveda, is rātri, which completely replaces the earlier words in post-Rigvedic Sanskrit and is the common or normal word in all modern Indo-Aryan languages as well as in all other languages which have borrowed the word from Sanskrit, but is totally missing in all the IE languages outside India (which had already departed before the birth of this word).

All these three stages are geographically located within India, and in fact the three Oldest Books (Maṇḍala-s) of the Rigveda (6, 3, 7, in that order) are geographically restricted to the areas in Haryana and further east (i.e. in the region to the east of the Sarasvati), and it is only during the course of composition of the Rigveda that the geography of the text expands northwestwards.

The Vedic language was constantly evolving. Therefore the further back we go into the past, before the composition of the first Rigvedic hymn, the more different the ancestral language will obviously be. If the linguists logically call this language "Proto-Indo-European", how can we object? We cannot insist it be called "Proto-Vedic" because it was also "Proto-Latin", "Proto-Greek", etc., being the ancestor of all these languages. The only fact is that it was located within India.

C. The PIE reconstructed by the linguists is a reconstructed approximation. It may contain several errors, but until someone among us can reconstruct a better version on linguistic principles (without consciously trying to make it look like Vedic Sanskrit), there is no sense in fighting against it as a whole (though every reconstructed point need not be blindly accepted). We need not grab every criticism of traditional IE linguistics by a professional linguist - who will obviously be wrong if he/she objects to the concept of the IE language family or the idea of an ancestral PIE - as something favorable to our interests.

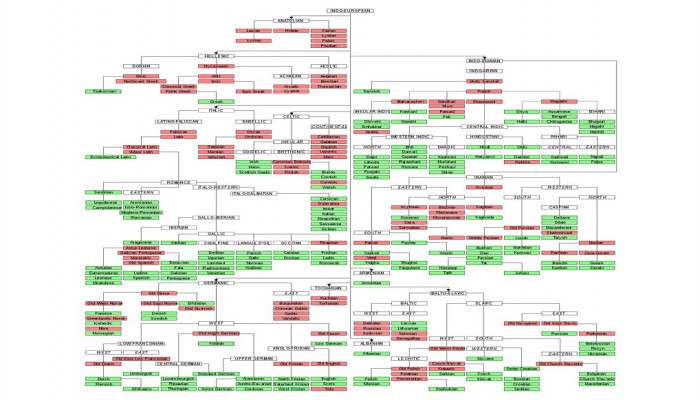

Image Credits: By Multiple authors, first version by Mandrak (Original work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons

Comments