The last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

- In History & Culture

- 11:23 AM, Apr 24, 2022

- Shaunak Agarkhedkar

The last major expedition of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration begins *after* Roald Amundsen and team reached the South Pole on 14 December 1911.

Five years earlier, the Nimrod Expedition had failed to reach the South Pole.

But they had marched to 88° 23' S, just 180.6km from the South Pole and the furthest south anyone had travelled until then.

The low-profile expedition — relying on private loans and individual contributions — was led by Ernest Shackleton who, after returning to Britain, began making plans for another expedition to the Antarctic.

His sights firmly set on the seventh continent, Shackleton modified his plans to "a transcontinental journey from sea to sea, crossing the pole" soon after news of Amundsen's feat reached him. By 1914, he had raised an estimated £80,000 and recruited personnel. The Endurance set sail for Buenos Aires on 8 August 1914 with 28 humans and a complement of sled dogs on board.

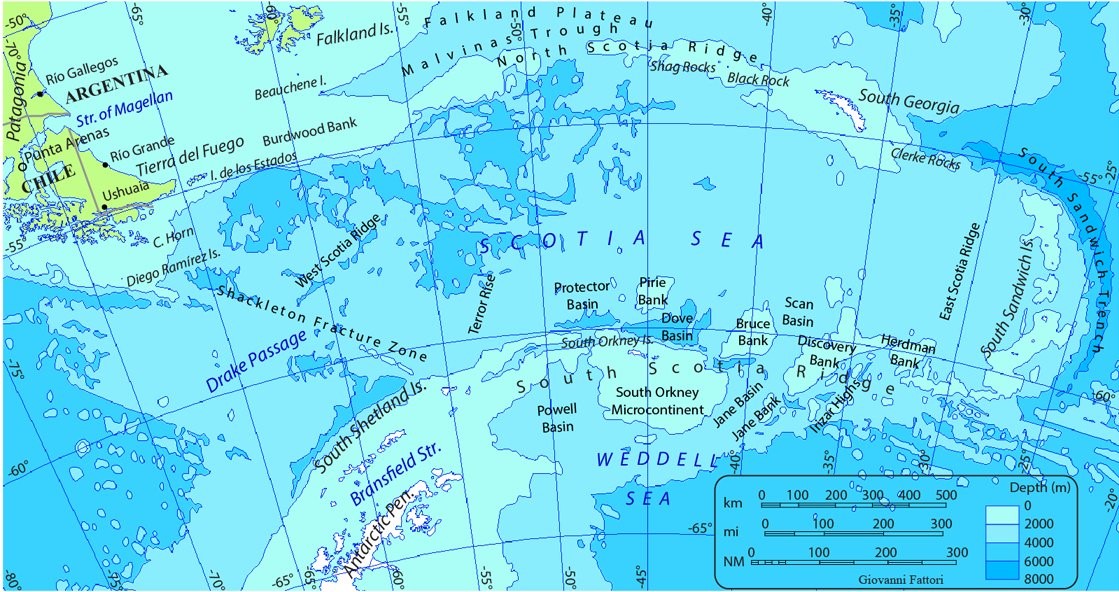

After halts at Bueno Aires and South Georgia, Endurance departed for the Antarctic on 5 December 1914. Just two days later, it encountered pack ice at 57° 26′S.

Pack ice is sea ice that isn't attached to the shoreline or to land. It expands in winter, and retreats in summer. Endurance had encountered it further north than expected, and was forced to manoeuvre around and through it. On 14 December, Endurance encountered pack ice thick enough to halt it for 24 hours. When the pack opened up, they continued sailing south, only to be halted once again three days later. Progress was slow and frustrating. "I had been prepared for evil conditions in the Weddell Sea, but had hoped that the pack would be loose," Shackleton wrote in his diary. "What we were encountering was fairly dense pack of a very obstinate character".

On 22 December, the pack opened up, allowing the ship to continue sailing deeper into the Weddell Sea, a part of the Southern Ocean known for strong surface winds that force the drift of ice northwards.

But it was anything but smooth sailing, and Endurance's progress was at the mercy of pack ice. Land became visible on 17 January 1915 when they reached 76° 27′S, but the weather turned bad and they had to seek shelter beside an iceberg. The next day, the ship found itself trapped once again in pack ice. It was now drifting with the pack ice. For days, crew tried their best to free the ship of ice and break a passage for it, but with very limited success.

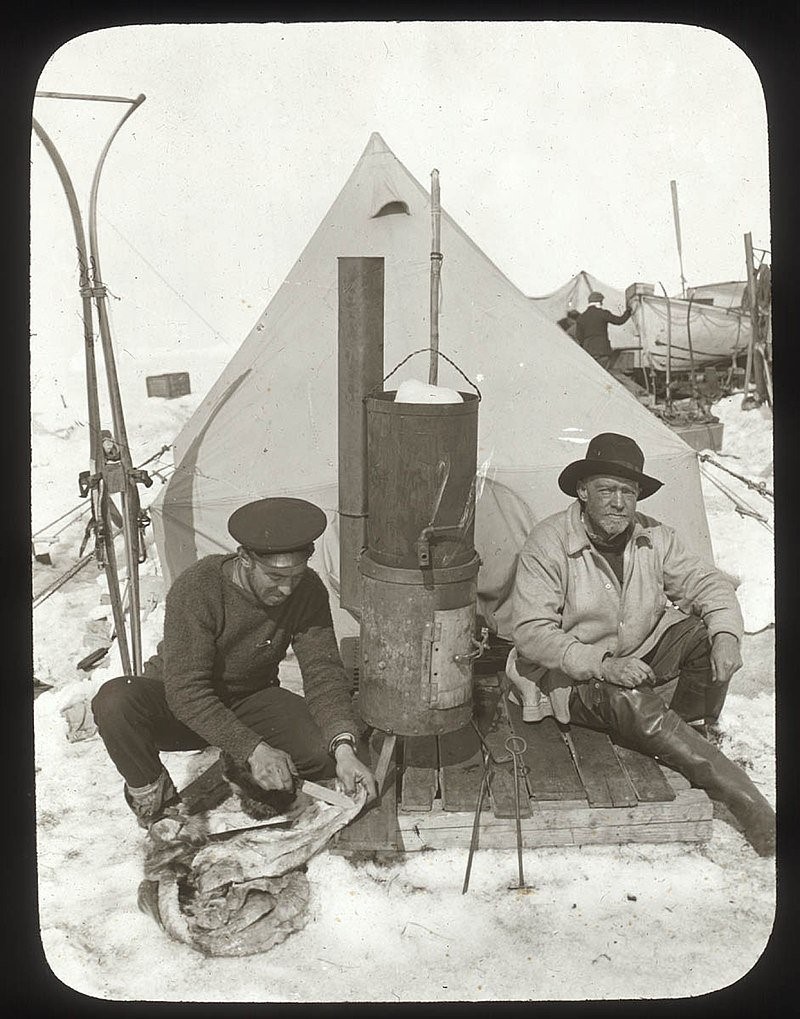

The ship remained stuck, drifting with the pack ice. On 21 February, it reached as far south as 76° 58′S. This was the furthest south it would travel, as the pack then began drifting northwards. Shackleton and crew now accepted that they would remain trapped through winter. The sled dogs were then removed from the ship and housed in igloos on the ice, and the crew began training and exercising them on ice floes.

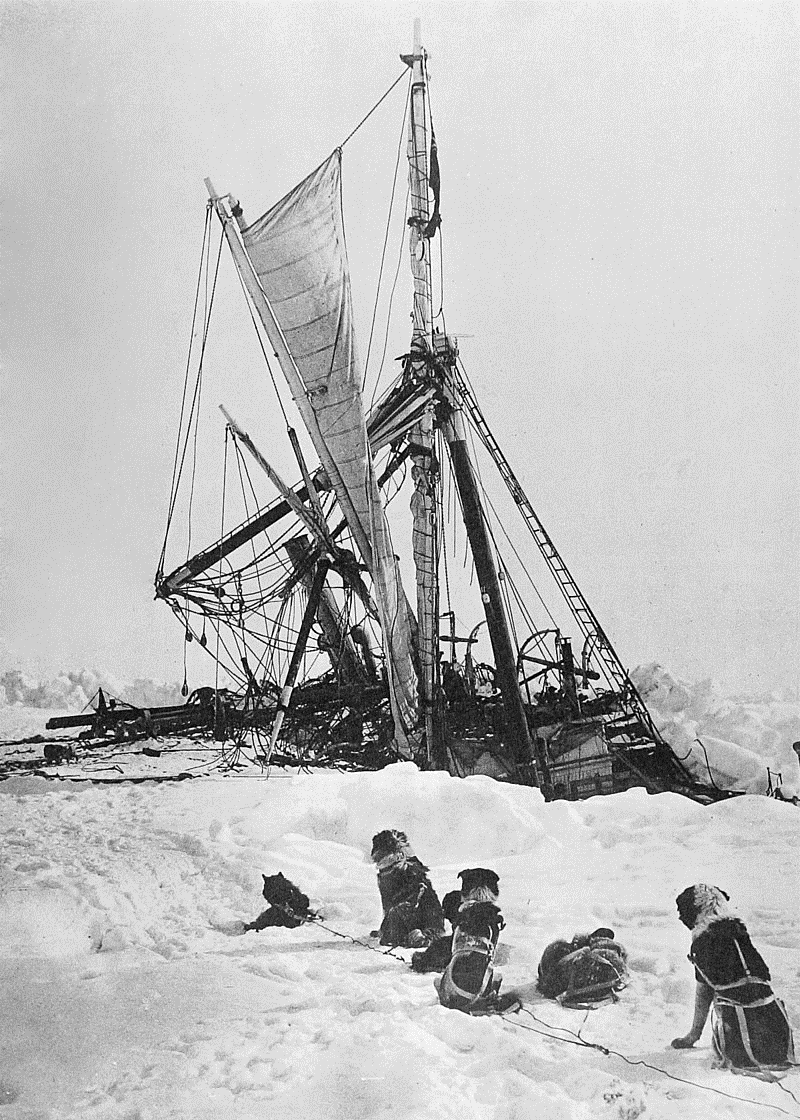

As winter set in, the pack ice's behaviour became ominous. As the wind drove more and more ice towards them, the ice floes began "piling and rafting against the masses of ice".This was 'pressure'. On 1 August, a heavy gale from the south-west resulted in ice floes around them slamming into each other. Large masses of ice got forced underneath the keel of the ship, causing it to list dangerously. "The effects of the pressure around us was awe-inspiring. Mighty blocks of ice ... rose slowly till they jumped like cherry-stones gripped between thumb and finger..." But the pressure did not continue, and the next few weeks were mostly uneventful. The pack ice continued drifting north, and their hopes of spotting land were dashed.

'Pressure' returned on 30 September, with the ship undergoing "the worst squeeze we had experienced". The crew were thrown about inside the ship as ice floes slammed into her sides and moved her about. She remained surrounded by ice, and unable to move. Over the next weeks, as 'pressure' increased, she would survive unscathed by slipping over the ice, rising from the surface of the water and from immediate danger. But on 24 October, the plucky ship's luck ran out. An ice floe trapped her starboard side, preventing her from rising as she had done on earlier occasions.

The pressure increased. The hull began bending, splintered. Freezing cold water began pouring in. Some crew members calmly unloaded supplies and two lifeboats onto the ice, while others desperately worked the pumps in icy waters to save the ship.As the pressure increased even further, the timbers that made up her skeleton began snapping like twigs. Even then, the crew worked the pumps. But it was a losing battle. Three days later, Shackleton ordered the crew to abandon ship. They would now live on the ice. The outside temperature was −26 °C.

Shackleton's objectives now shifted from the transcontinental journey to survival. He planned to journey west over the ice to Paulet Island, a tiny speck of land to the north of the Waddell Sea barely 400m in diameter. But it hosted a hut containing substantial food supplies. They loaded supplies and two lifeboats on sledges, and set off. Almost immediately, they ran into problems. The ice was scored with pressure ridges that were tens of feet high. To overcome them, the crew would have to cut a pass in them that was wide enough for the lifeboats.

Three days later, having only travelled two miles, Shackleton abandoned the plan. They set up camp on a solid-looking ice floe. This was 'Ocean Camp'. The crew returned to the stricken ship to salvage more supplies and the third lifeboat, the largest.

The pack ice wasn't done with Endurance, however. Each day the ice would drive further into her sides, skewering her, until she sank on 21 November.

The ice continued drifting, carrying the crew northwards at a leisurely pace towards Paulet Island. But then the direction changed, taking them further east than they would have liked. It now looked as if they would miss Paulet Island.

So, Shackleton and crew began another march westwards, carrying a part of the supplies and two lifeboats. But temperatures had risen, and the ice was mushy, making movement difficult. Men would sink to their knees in soft snow. Each step chilled them to the bone and sapped energy. This time they travelled 7.5 miles in two days before deciding to halt. They set up tents once again and settled down to life on the ice in 'Patience Camp'.

Teams were set back to 'Ocean Camp' to retrieve more supplies and the third lifeboat.Food shortages became acute as days turned into weeks. They hunted seals and began surviving on seal meat, conserving packaged rations. But the dogs also needed to be fed, and their appetites were significant.

In January 1916, with their supplies of seal meat also dwindling, Shackleton ordered most of the dogs to be shot. Only two dog teams remained. They too would be shot in April, and their meat would be consumed by the crew.

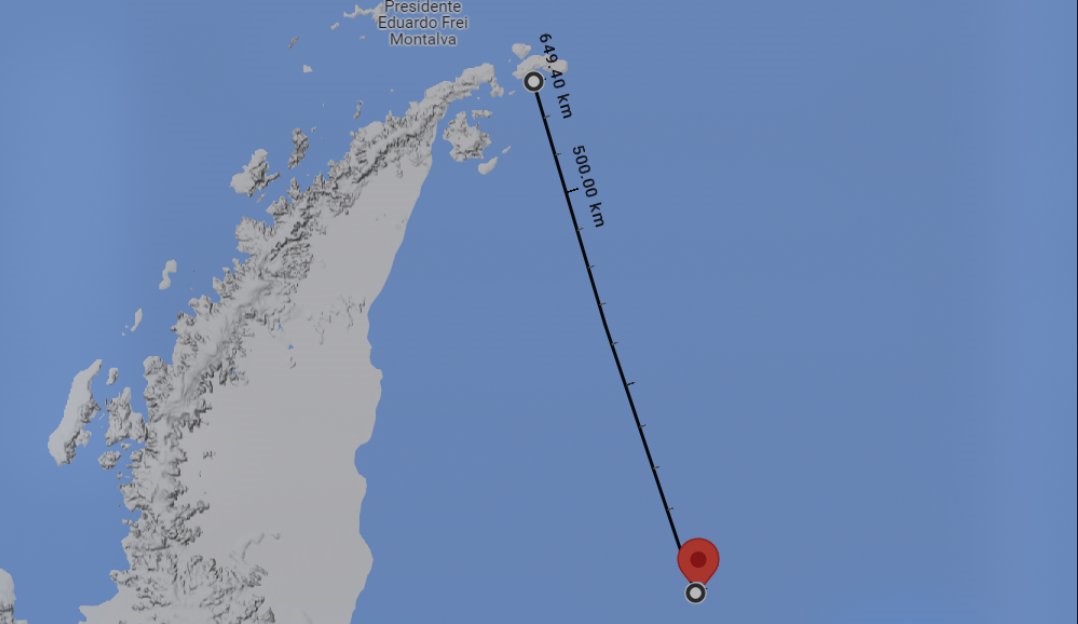

On 17 March, the pack drifted to Paulet Island's latitude, but 60 miles east. They were in a precarious position now, with the ice taking them straight towards the South Atlantic Ocean where, once the ice melted, they would meet a watery death.

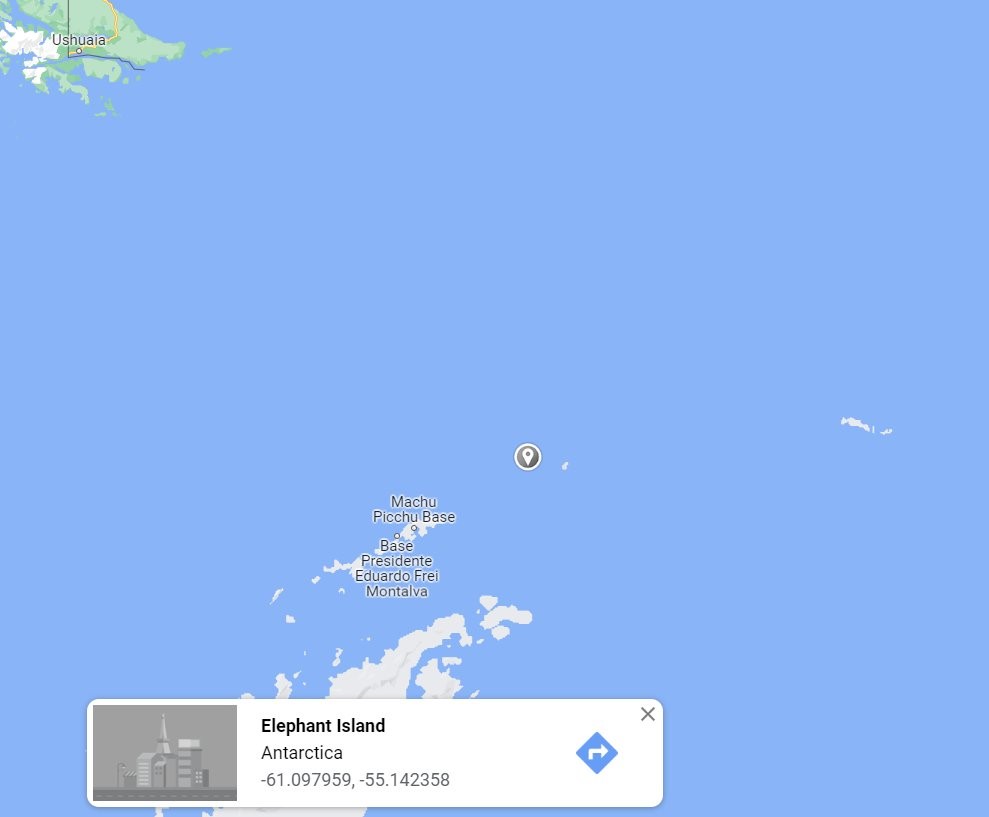

The ice carried them north of Paulet Island. Their hopes for survival now depended on two tiny, uninhabited islands about 160 miles to the north: Elephant Island, and Clarence Island. There would be no supplies waiting there, but at least they'd be on solid ground.

On the evening of 8 April, the ice floe they were drifting on split down the middle. They saved their supplies and boats in the dark, and a crew member who had fallen into the fissure was pulled out by Shackleton moments before the two parts slammed back into each other. The ice was beginning to crack all over, giving them what they had dreamt of for months: a water passage to launch their lifeboats.

An hour after midnight, they launched the boats and began rowing like hell to get out of the labyrinth of drifting floes. The voyage was fraught with danger, as passages opened and closed before them.

When they found it impossible to proceed, the crew would drag the boats up the nearest floe and wait for better conditions. The temperature fell as low as −29 °C. After a harrowing journey through the ice, followed by a stormy voyage in the freezing sea, they were within sight of the 3,500 foot peaks of Elephant Island on 14 April. But the wind kept them from approaching closer than 10 miles.

Shackleton was in command of the largest of the three lifeboats. He ordered all three to be tied together, hoping that sailing together they would make better progress. And when the wind died down, they rowed with everything they had. But the island remained just as far. As night fell, the wind changed direction and picked up speed to 50 miles an hour.

In the dark, struggling to make himself heard, Frank Worsley — Shackleton's second in command and brilliant navigator — suggested his boat the 'Dudley Docker' might have better luck on its own.

With Shackleton's permission and instructions to stay in sight, the Docker cast off. The crew struggled against icy winds and freezing spray, and the boats against ocean currents and the wind. Around midnight, Shackleton lost sight of her. He tried to signal the Docker using matchsticks. Worsley saw it and tried to signal back. But just then the Docker was caught in a fierce rip tide, and Worsley and crew busied themselves trying to remain afloat. At one moment, the Docker would be slammed by the crest of an unseen wave.

Just as the crew realised what had happened, it would drop into the deep, dark trough. It took everything Worsley had to keep the boat facing the wind, and by 3am, eyes hurting from staring into the wind for so long, he couldn't stay awake anymore. They had been sailing for five and a half days. Another member of the crew relieved him, and Worsley — who had frozen in position — had to be carried so that he could rest.

Greenstreet, who now manned the tiller, did not know their exact location. He was terrified of the possibility that they might sail through the 14 mile gap between Elephant and Clarence Islands, which led to the Drake Passage. The Drake Passage lies between Cape Horn and the Southern Ocean. It is one of the stormiest places on earth, with strong currents and waves that can be as high as 40 feet.

Greenstreet and Macklin struggled through the night, navigating on a south-west course by a tiny pocket compass, and praying that they hadn't already been swept into the Drake Passage. As dawn arrived, they were greeted by the sight of Elephant Island looming dead ahead. They had survived the night. The island was no more than a couple of hundred yards away, and all seemed safe.

Just then, wind swept down from the cliffs before them and hit the water at 100 miles per hour. It drove a wave as high as the Docker towards it. Greenstreet had the men drop sail, and struggled to keep the boat pointing at the wave. He saw another wave following it, this one was six feet high.

In the pandemonium of the crew trying to survive the onslaught of wind and water, Worsley awoke with a start. Instinctively grasping what was happening, he ordered them to hoist sail and steer away from the island. Greenstreet pulled the tiller with all his strength. The boat had just turned and the sail caught the wind when the first wave was upon them. Water poured into the boat, almost knocking Greenstreet off it. A moment later, the second one arrived.

Half filled with water, the Docker began riding lower in the water. Another wave would kill it. Worsley took over the tiller and guided the boat to safety while the crew began bailing water furiously. They used mugs, cups, even bare hands to throw water over the side.

As the boat emptied, Worsley guided it to safety near the island. Dawn saw the third lifeboat, the 'Wills', still tethered to Shackleton's boat, the 'Caird'. They sailed past the north-east tip of the island and began looking for a place to land. But all they could see were vertical cliffs and glaciers. It took a lot of searching before Shackleton spotted a tiny beach hidden behind rocks.

As the two boats rowed towards it, the Docker sailed towards them from the other side, each group having thought the other lost to the sea in the night. The crew eventually made it to the beach. It was a hundred feet wide and fifty feet deep, but it was solid land at last. Each member of the crew had survived the voyage in lifeboats. But just then, exhausted beyond belief, Lewis Rickinson suffered a heart attack.

He survived. The men spent the next day eating and sleeping. Once they had recovered some of their strength, Shackleton gave them the bad news. They would have to move. The cliffs around the beach bore marks of a high tide that would inundate the entire beach and wash them out to sea.

The Wills was sent with a crew of six to find a suitable place. It took them all day and evening to find a patch of land 150 yards long and 30 yards deep. It had a penguin rookery. The next day, all three boats set sail for the new location. The wind was raging along the way. As they came upon a large rock a quarter of a mile offshore, the Caird and Wills turned towards the island to pass it. But Worsley took the Docker seaward of the rock.

Immediately, the Docker was caught by the full force of the wind. As the crew struggled against wind and current, Worsley shouted to Greenstreet to take the tiller.

Taking one of the three oars himself, Worsley set a furious pace. Together, the three oarsmen began dragging the boat back towards the island inch by hard earned inch. The current then tried to hurl them at the rock. Thrice. They managed to avoid getting battered to bits, and began closing on the shore. Just then, another gust of wind flew down the cliffs towards them. Worsley grabbed the tiller from Greenstreet and navigated like his life depended on it, which it did.

The Docker finally made it past the reef to the patch of land, but just barely.

The crew hunted a couple of seals for food, and used the Docker and the Wills to build shelter. But Shackleton would not let them use the Caird. His journey had just begun.

On 20 April, Shackleton told the crew that he would take a party of five and set sail in the Caird for South Georgia. It was eight hundred miles away. And the Drake Passage and the Scotia Sea lay in between.

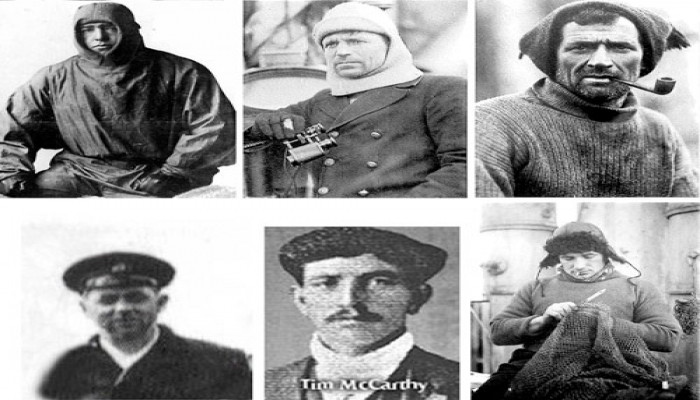

The voyage would take them nearly a thousand miles through the stormiest waters on the planet. Their target was just 25 miles wide. If they missed, they would be adrift in the South Atlantic. He chose the brilliant Frank Worsley as his navigator. McNeish, Crean, McCarthy, and Vincent made up the remainder of the Caird's crew.

After loading the Caird with two 68-litre casks of water and food sufficient for six weeks, they set sail on 24 April 1916.

Ice fields were beginning to form to their north-east along the direction of South Georgia, so they set a course due north. By the next morning they had left the ice behind. But they were sailing in 50mph winds and waves up to 30 feet high. Each wave that broke over the boat left them drenched and freezing, and struggling to bail water. But the Caird soldiered on.

After two days, sightings of the sun showed that they had sailed 147 miles north of Elephant Island. Worsley set a direct course for South Georgia. On 29 April, fresh observations by Worsley showed that they had sailed 274 miles. After that, clouds and fog made further observations impossible for a long time. The seas were rough. With the Caird taking on water, it was kept afloat by continuous bailing.

During the voyage, the temperature dropped and ice began forming on the surface of the boat through the night. At dawn, the boat was dangerously low in the water. Shackleton crawled over and, using the back of an axe, began smashing the ice and throwing it overboard. When he got tired, other crewmembers took turns. Gradually, most of the ice was thrown overboard and the situation became a bit less precarious.

The sea then threw a storm at them, threatening to rip the sail off the boat's mast. The crew rigged a sea anchor out of a large piece of canvas, and spent 48 hours hanging on for dear life before the storm abated.

On 5 May, they encountered huge waves that flung the boat all over the place. The crew worked without rest to bail water in a desperate struggle to keep the boat from capsizing. Observations on 6 May showed them to be 132 miles from South Georgia, but by 7 May Worsley felt that he couldn't tell their position accurately. Shackleton changed course slightly to avoid being swept past the island.

"Things were bad for us in those days", wrote Shackleton. "The bright moments were those when we each received our one mug of hot milk during the long, bitter watches of the night".

Later that day, they spotted seaweed floating in the water. The next morning, they saw cormorants. South Georgia was first spotted just after noon on 8 May. But they weren't out of the woods yet.

The Caird had run out of drinking water on 6 May. By the time the mountains of South Georgia deigned to give them an audience, their throats were parched, lips were bleeding, and they had gone far beyond the limits of exhaustion. By mid afternoon, they were just 3 miles from the coast and could make out vegetation. Luck finally appeared to be turning their way.

Just then, they heard the deep roar of waves crashing on the island. A few minutes later, they saw them. The size of the waves made it clear that the boat would not survive. Land was within reach, and yet they couldn't sail to it. Worsley and Shackleton pored over a chart to try and find a suitable landing spot. They estimated that King Haakon Bay was 10 miles to the east, while Wilson Bay was just north, on the other side of the island.

The winds bearing down on them from the northwest would make sailing to King Haakon Bay dramatically dangerous, and they wouldn't reach it by nightfall. But sailing to Wilson Bay would require them to go around the island.

At 3.10pm, Shackleton decided that they would head back to sea and wait the night out. At 6pm, it became dark. By 11pm, a storm was raging around them, and the Caird was tossed every which way by an angry sea throughout the night. Dawn was misty and bleak. The wind was fierce, there was a distinct swell in the sea, and the breakers they had heard and seen yesterday were even louder. When the mist allowed them a glimpse, the breakers seemed 40 feet high. They couldn't see the island, and by noon the wind had strengthened to a terrifying 90 miles an hour.

Worsley kept the bow pointing into the wind, struggling to keep the boat afloat while everyone else peered into the gloomy mist for a sight of the island. At 2pm, the mist cleared and they found themselves a mile from the vertical faces of giant glaciers. More worryingly, they were dangerously close to where the breakers formed and rushed to the island.

With each swell, the sea tugged at the boat and tried to dispatch it to its doom on the island. They hoist the sail and tried to get away, but the wind was blowing against them and the boat did not budge. Shackleton then grabbed the tiller and pointed the boat south-east. The wind slammed into her side and almost capsized her. The crew feverishly shifted ballast — rocks loaded onto the boat — until it righted itself. The boat began moving parallel to the shore, but then a big wave struck, dumping water into it. The wave also caused her planks to open a bit, and water began squirting into the boat through her hull.

Engulfed once more by the mist, the crew worked like maniacs to bail water. An hour elapsed. When the mist parted, it appeared the boat hadn't moved at all. Shackleton was certain it was the end. But they were making progress. The outline of the coast wasn't distinct enough to notice it, but the boat, despite everything thrown at it, was moving.

Around 4pm, as the storm blew the mist, it revealed a large hulking mass. Annenkov Island, a 2,000 foot mountain five miles off the coast, lay directly in their path. They couldn't turn away from the sea: that way lay reefs that would wreck the boat in seconds. They couldn't turn away from the island: the storm blowing against them was too strong.

So they continued, bow pointed at the sea, drifting parallel to the coast and at the mountain. By 7.30pm, they were almost upon the mountain, and they had to crane their necks to see its snowy peak. But just as Worsley, who was at the helm, sat anticipating the end, he noticed the sky ahead. The Caird was clearing the mountain. Some unexpected tide had kept them from crashing against its sheer cliffs. As if realising that the boat had survived its toughest ordeal, the storm abated a few minutes later. The crew continued bailing until midnight, when the water was low enough to rest.

At 7am the next morning, South Georgia came into view. It was 10 miles away. They set course straight for it, but the wind died down, making progress excruciatingly slow. By noon they were back at Cape Demidov, exactly where they had noticed the breakers the previous day. But this time they set course for King Haakon Bay. After making good progress, the wind swung around and began blowing them backwards.

Lowering sails, they began rowing their hearts out, fighting against the wind. Then the tide turned, and began carrying them out. By three, they had spotted a quiet landing spot. But rowing wasn't going to get them there, not before nightfall. And nobody on that boat fancied another night in the sea off the island's coast. They ran up every sail to try and make a dash for a gap in the reef, but failed to make headway.

Shackleton sailed her south for a bit, then tried again. It was getting dark. Desperate times. Luck finally smiled, and the boat made it through the reef by the skin of its teeth. Dropping sails immediately, they took to oars again. After ten minutes of rowing, they finally slipped past another reef. The Caird's keel ground her against rock. And Shackleton jumped ashore at 5pm on 10 May 1916, 522 days after they had last sailed from South Georgia.

But it wasn’t the end of his journey. Not yet. Their strength was gone, and they couldn't haul the Caird up the shore. So, they tied her to a boulder and left her at the edge of water. Around 2am, the sea caught her. The rope broke, she began drifting into the sea. Tom Crean was on watch. He ran into the water and held on to the rope for dear life. His shouts woke the rest, but by the time they reached him, Crean had been dragged deep, and had almost drowned.

During this, the Caird lost her rudder. Shackleton's hopes of sailing her around the island to the whaling station after a few days rest were dashed. The next morning, Shackleton decided that instead of sailing around the island, a voyage of 130 miles, three of them would cross it on foot. The straight-line distance was 29 miles. But nobody had crossed the island on foot, and for good reason.

Not only did its peaks almost rise to 10,000 feet, the interior was a maze of ridges and glaciers, peaks and crevasses. After two days rest, they loaded the Caird again and sailed a few miles in pleasant weather to a gently sloping beach populated by hundreds of sea elephants.

There, McNeish removed two-inch screws from the boat and fixed them in three pairs of boots. At 3.10am on 19 May, Shackleton, Worsley, and Crean set off for the interior of the island. The slope levelled off around 2,500 feet.

At this point their map was useless, because on it the interior of the island was completely blank. At 5am, as fog rolled in, they roped themselves together using 50-feet of hemp rope salvaged from the Caird.

Following the gentle slope downward, it was only an hour later that they realised they were descending a glacier. At 7am, when the fog cleared and the sun rose, they saw that they were actually headed along the glacier for Poseidon Bay and the open sea beyond it.

Retracing their steps took hours. Absent warm clothing or sleeping bags, they were one storm away from hypothermia & death. They then climbed a mountain range, a steep ascent that required them to cut steps into the snow with a carpenter's adze, and summitted around 11.15am. On one side lay a steep drop. On the other, steep glaciers descending to the sea. In their way lay a gently rising slope of snow.

But first they'd have to descend to it. Which meant retracing their steps once again, and skirting the base of the mountain. They climbed that slope by 3 in the afternoon, and saw a descent that was steep and frightening. But the fog was rolling in, and it looked like it might rain. Hypothermia loomed on their minds. They cut steps on their way down using the adze, and then climbed the next peak by 4.30pm.

It was getting darker, so they pushed forward, descending once again with the aid of the adze. But Shackleton realised that they were moving too slow to make it on time. The storm would catch them up high, and they'd die of exposure.

Noticing a gentle, snow-covered slope leading down their path, he suggested they slide down it to lose altitude rapidly. Worsley and Crean weren't keen, but when Shackleton demanded to know if they had any alternative in mind that didn't end in certain death, they grudgingly agreed.

The three of them held each other tight, and then Shackleton pulled them off the ridge and onto the slope. After a terrifying slide during which the wind roared in their ears, as did each other, they came to a halt in a snowbank, having descended 2,000 feet in a few minutes and survived. The three of them continued their eastward march up and down slopes, until they caught sight of Stromness Bay.

After a short descent, they came across a crevasse. Which meant something was wrong. There were no glaciers near Stromness Bay. They had misread the landmarks. Instead of Stromness Bay, they had approached Fortuna Bay, and now had to retrace their steps in the moonlight. Beyond exhaustion, they took shelter behind a rock and rested. Shackleton found himself nodding off, and jerked awake.

Experience had taught him that he was about to slip into hypothermia. After a few minutes, he woke the others and told them it was time to continue. At 6.30am, while eating the last of the food they were carrying, they thought they heard a steam whistle. If it was from the whaling station at Stromness Bay, it would sound again at 7. They counted down. It sounded again precisely at 7.

Possessed with energy they didn't know they had, they pushed on, ascending and descending ridges until they climbed one and were welcomed by the sight of the whaling station down below. Descending towards it, they began following a stream that became broader and broader before ending in a waterfall. It was nearly 3pm, and they didn't have the time to find another route. So they tied the rope to a boulder and descended it.

A little after 4pm, Mathias Andersen was about to end his shift when he saw three wild men approach the whaling station. They asked to be taken to the manager. When Toralf Sorlle opened the door of his cabin, he stared in disbelief at the three men standing before him.

"Who the hell are you?" he finally asked. "My name is Shackleton," the man in the middle said. Some say that Sorlle turned away and wept.

After a bath and a shave, Shackleton took a whaler back to the bay where he had left the remaining crew on South Georgia. That evening the whalers gave them a reception, and veterans of the Southern Ocean, old men who had sailed there for forty years, solemnly shook hands with the people who had sailed a 22-foot boat through the Drake Passage to South Georgia.

This is the Caird, a tiny boat. After that, he tried multiple times, and with many different vessels, to rescue his crew on Elephant Island. But it was surrounded by thick ice, and the vessels weren't up to it. He finally pleaded with the Chilean government to lend him the sea-going tugboat Yelcho, and sailed with Worsley and the rest of the crew on 25 August.

And on 30 August, the Yelcho reached Elephant Island.

Every one of Shackleton's crew who had been left behind on it survived. Each one of the 22 was rescued. If you've read this far and found this story interesting, I cannot urge you enough to read Alfred Lansing's lovely book 'Endurance'. My summary does not compare to Lansing's brilliant narration.

All the images are provided by the author.

Comments