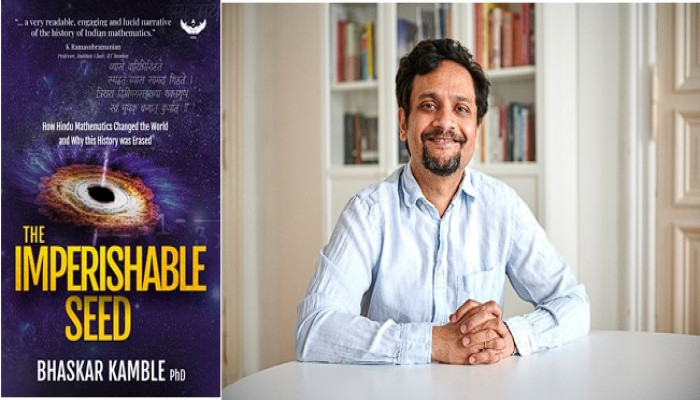

The Imperishable Seed: How Hindu Mathematics Changed the World and Why this History was Erased

- In Book Reviews

- 07:25 PM, May 15, 2024

- Richa Yadav

“One example of the state of indigenous knowledge in ancient and medieval India comes from the field of medicine; specifically, from the field known as rhinoplasty, which is a branch of plastic surgery. Today, plastic surgery is believed to be a Western innovation and a modern development in medical history. What is generally overlooked is that it was practiced in India since centuries before it became popular in the West, and it went to the West from India, after it was observed and copied by British surgeons in the early nineteenth century.”

- Bhaskar Kamble Chapter 13. Pg.300

Well, perhaps reading such descriptions led scholars like Yuval Noah Harari, an Israeli author and public intellectual to say in his book 21 Lessons for the 21st Century that countries make some insane claims, “Needless to say that British, French, German, American, Russian, Japanese and countless other groups are similarly convinced that humankind would have lived in barbarous and immoral ignorance if it wasn’t for the spectacular achievements of their nation.” (Harari. Chapter 12, Humility)

He continues, “Most people tend to believe they are the centre of the world, and their culture is the linchpin of human history. ...Hindu nativists dismiss these Chinese boasts and argue that even airplanes and nuclear bombs were invented by ancient sages in the Indian subcontinent long before Confucius or Plato, not to mention Einstein and the Wright brothers. Did you know, for example, that it was Maharishi Bhardwaj who invented rockets and aeroplanes, that Vishwamitra not only invented but also used missiles, that Acharya Kanad was the father of atomic theory, and that the Mahabharata accurately describes nuclear weapons?!” (Harari. Chapter 12, Humility)

Are these Indic claims baseless? If you are also thinking that such ‘Hindu far right’ claims might not hold much water, do check out the book by Bhaskar Kamble. He does talk about several mathematical feats achieved by Hindu civilisation long before we could imagine, certainly, with real references.

If you ask an average Indian about the country’s contribution to the field of Mathematics, the most expected answer you will receive is that ‘zero’ was discovered in Bharat. A peek into this book The Imperishable Seed will allow you to revisit the legacy of Indian mathematics and offer several proofs to believe that ancient Hindu mathematics has contributed much more than ‘zero’ to the world. By the end of the book, you will learn how various mathematical concepts including value π, the sum of arithmetic and geometric series, combinatorics, the decimal number system, and trigonometry were developed and perfected in the Hindu civilization.

He discusses a long list of topics that could trace their origin in Hindu mathematics- the Fibonacci sequence, binary numbers, algorithms, Pell’s equation, binomial theorem, Gregory Leibniz series, and Pascal’s triangle—all of these are described in the texts of the Hindu mathematicians.

At the outset, the author clarifies that by ‘Hindu mathematics’ he means the mathematics of the Sanskrit scholars following the Vedic tradition specifically referring to the tradition from the Vedas as well as the mathematics of Buddhists and Jains.

It is amazing to learn that ancient Indian grammarians Panini and poet and mathematician Pingala developed some algorithms and systems that have even influenced the modern discipline of computer science. Panini formalised the grammar, syntax, and phonology of the Sanskrit language in an exhaustive set of rules in his most important work, the Ashtadhyayi written around 2,500 years earlier than the works of John Backus, Noam Chomsky, Emil Post, and Axel on the structure of programming languages as their work bears deep similarities with Panini’s work.

If the East had so much to offer in mathematical knowledge, why would most of the world remain oblivious to the contribution of Hindu mathematics to the world? Why do mostly Western narratives dominate in the name of modern, scientific knowledge in academia?

This is because a false narrative was set by the West, explains the author, Dr. Bhaskar Kamble, a Theoretical Physicist and a Data Scientist by profession in his book published in 2023. He digs deeper into the cause of this incorrect narrative which was built and sustained to date and explains that there are two main reasons for this; the first is that the Biblical tradition exercises a powerful hold on academics and knowledge systems in the West calling it ‘universal’; the self-proclaimed ‘universal’ Western knowledge system invalidates other knowledge systems not born in the Judeo-Christian framework as secondary and inferior to their own.

In other words, Western values and standards are supposed to be ideal, and worthy of being followed as they are ‘universal’ in some sense, whereas the knowledge systems of others are considered to be backward or primitive and quite ‘local’. Such false claims of universalism are made both in religion and in secular knowledge systems, although both belong to realms that are incompatible with each other.

Another reason that Bhaskar explains behind sidelining Hindu contribution to mathematical knowledge was that the colonisers tried their best to show Hindu native culture as derogatory so that they could justify their plans to persuade ‘pagan followers’ towards Christianity. This gave the West a sense of inherent superiority over their worldview and helped them gain control of the power structure in their colonies. This empowered the colonisers to convince the world to become followers rather than rulers.

The book reveals how some major concepts of Hindu mathematics such as the number system and decimal system got translated into Arabic and reached to the Arabs and subsequently to Latin and reached Europe. As a result, the credit and ownership of discovering these concepts shifted elsewhere from Hindu civilisation.

Similarly, Hindu mathematicians’ invaluable knowledge of calculus wrongly reached Europe via the Jesuits who had come to Bharat to preach Christianity to the ‘pagans of Bharat’ and could lay their hands on the invaluable knowledge to pass on to their continent. Today, calculus is considered to be the sole achievement of Western mathematics, and it is held that Newton and Leibniz were their independent discoverers. The author explains how the foundation of concepts of calculus in India was found several centuries before it was developed in Europe. In the 14th–16th centuries the Kerala mathematicians had also developed most of the ideas of calculus such as differentiation, integration, and infinite series more than three centuries before their discovery in Europe.

Furthermore, Bhaskar explains that Indians possessed sophisticated knowledge of trigonometry which was important to the science of navigation and cartography. Several European Jesuit missionaries also traveled to ‘pagan’ lands to spread the Catholic faith and in search of the navigational knowledge to increase the safety of sea voyages; in return, they took away translated Sanskrit texts full of an advanced knowledge system and reclaimed it as their own. Therefore, for a long time and in different ways, this knowledge was transmitted to Europe through the Greeks, Arabs, and Jesuit priests.

Another significant contribution of the book lies in a beautiful explanation of how mathematics in the Indian civilisation relates to the deeper knowledge framework and the philosophy of Hindu civilisation. Dr. Bhaskar emphasises deep connections between this mathematical knowledge and the Hindu philosophical framework. According to the Hindu worldview, the whole of existence can be divided into two categories: the observed and the observer, or the ‘apara’ and ‘para’ prakriti, respectively.

The concept of apara prakriti is about the ‘observed’, the material world which consists, of the physical universe of matter, space, and energy; it also includes the physical body and all things related to mental and intellectual activities such as emotions, thoughts, and the ego.

The second category of existence is the ‘observer’ or the para prakriti; it is the knowledge of the self, and the supreme consciousness, the Brahman. The observer stands apart as an impartial witness of the observed and consists of pure consciousness. Para vidya aims to obtain knowledge of the self by casting off false associations overcoming ignorance and ‘knowing’ the self. Therefore, before we learn about this transcendental aspect of consciousness, the observer, there is much to unfold to make sure we are not merely looking at the ‘observed’ or apara aspect of consciousness.

Thus, consciousness and matter are not mutually exclusive but two aspects of reality in Indian civilisation. This inclusive approach led to profound developments in various fields of apara vidya, such as all the natural sciences, engineering disciplines, medicine, linguistics, and mathematics to gain a better understanding of the world. This is in contrast to the dualism of the Western framework, where spiritual knowledge is reduced to the dogma of religions, and scientific knowledge is considered materialistic hence making the status of consciousness something mystical.

The main contribution of the book lies in explaining how this materialistic framework of the West limits all knowledge to a materialistic worldview, unlike the Hindu knowledge system which brings philosophy and mathematics together as the dominant thought is to know the material to go beyond and experience the non-material, super consciousness.

Dr. Kamble explains the reason why he chose the name of the book as an imperishable seed. While arithmetic deals with vyakta, or known numbers, algebra deals with avyakta, or unknown quantities, and manipulates these symbols to find the unknowns or to express general results or to prove certain propositions, that are represented as symbols. Hence, there is an interplay of the known and the unknown. Algebra shows the interplay between Hindu philosophy and mathematics by revealing how the unmanifest, the avyakta, another name for Brahman could be explored in a symbolic form.

In a nutshell, be it the so-called Pythagoras theorem or trigonometry in the case of mathematics or be it astronomy, or any other science, the Hindu knowledge system began stretching its limits way before the other geographical areas explored and discovered these truths. Dr. Bhaskar mentions that the so-called Pythagoras Theorem appears in the Sulbasutras, which again are part of the Vedas. It is possible that Pythagoras had traveled to India himself and came to know of the theorem, now named after him, from India.

The entire blame for not recognising the Hindu roots of most of these mathematical concepts lies not only in the Western narratives but also in the ignorance of Hindus and our education system. Due ownership and credit of these lofty mathematical concepts went elsewhere because we have not taken the trouble to understand our heritage and civilization.

This book might encourage the readers to learn more about the origin of mathematical dimensions. We need to include this information in our curriculum and find ways to bring back this scientific curiosity to continue the work done by our ancestors.

What lessons can we learn from this approach? Can we at least muster the courage to develop these works and have confidence in our heritage? In my view, it is less about getting due credibility in the eyes of the West than giving our future generation to look up to where they belong and seek motivation to further work towards contributing to this rich cultural heritage. They should be informed about their vast knowledge system so that we could have more scholars to take this forward.

Image source: Nehru Centre

Comments