The Eternal Resistance of Somanath

- In History & Culture

- 11:23 AM, Feb 10, 2024

- Jeevan Rao

सौराष्ट्रदेशे विशदेऽतिरम्ये ज्योतिर्मयं चन्द्रकलावतंसम् |

भक्तिप्रदानाय कृपावतीर्णं तं सोमनाथं शरणं प्रपद्ये || १ ||

I seek refuge of the Somanatha,

Who is in the holy and pretty Sourashtra,

Who is dazzling with light,

Who wears the crescent of the moon,

Who has come there to give,

The gift of devotion and mercy.

-Adi Shankaracharya.

On 22nd January 2024, the entire nation celebrated the historic occasion of the pranpratishtha of Ram Lalla at the Ram Janmabhumi Mandir, Ayodhya. The majority of Indians felt that a historic wrong done to the Hindus was being reversed, marking the end of a long wait of 500 years. Did you know that the actions of the “Iron Man of India”, Sri Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, were the inspiration behind the Ram Janmabhumi movement? Within just 3 months of the Independence, Sardar Patel had taken an unprecedented decision to rebuild the Somanath Jyotirlinga Mandir thereby healing a civilizational scar borne by millions of Indians across generations. It was the collective weight of 900 years of atrocities that had compelled Sardar to undertake such a herculean task. The story of Somanath is a tale of devotion, sacrifice, intolerance, bloodlust, and above all, the undying spirit of the followers of Sanatana Dharma.

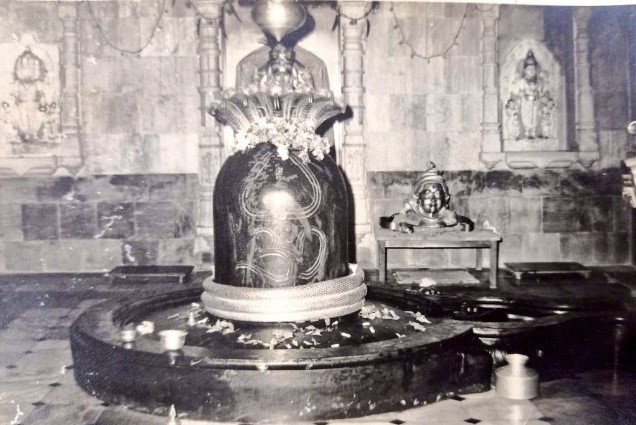

The Jyotirlinga at the Somanath is believed to be the first among the twelve Jyotirlingas located along the length and breadth of the Indian subcontinent. The story behind the Jyotirlinga is that when the lustre of Soma (Moon) had waned due to a curse from his father-in-law Daksha, he prayed to Bhagawan Shiva on a seashore. Shiva pleased with the devotion of Soma, cured the curse and Soma regained his earlier lustre (Prabha). Thus, that land came to be known as Prabhasa and Shiva as Somanatha (the lord of Soma).

Apart from being the dwelling place of Somanatha, the land of Prabhasa also has a connection to Bhagawan Krishna. According to the Mahabharata, Sri Krishna departed from this world by leaving his mortal coils near the shores of Prabhasa. Even to this day, people bow with reverence to the places associated with the incident such as Ban Ganga—from where the hunter shot the arrow, Bhalka teerth—where Sri Krishna was struck by the arrow and Dehotsarga teerth—where he was believed to be cremated. Due to such multiple associations with the Gods, the land of Prabhasa was seen as a sacred religious site by the Hindus since time immemorial.

A small stone mandir of Somanath existed in Prabhasa around the 1st–2nd century CE. However, it is possible that a mandir built using wood existed at this site even before the construction of this stone mandir. This period was identified because the painted pottery ware ascribable to the early centuries of the common era was found along with a broken shikhara during the excavation. This mandir probably went out of patronage during the rule of the Guptas who were more inclined towards Vaishnavism.

Between the 6th and 7th centuries CE, the Vallabhi rulers constructed a moderate second mandir using Kanjur stones. This mandir incorporated the carved stones of the first mandir into its lowermost foundations. During an excavation of the mandir premises, a stone slab inscribed with the Brahmi script from the Vallabhi period was discovered, which aided in assigning the structure to this period.

A bigger third mandir was built with thin-grained red sandstone over the plinth of the second mandir while reusing the materials of its predecessor, mainly for the foundation. This was a strong imposing structure built during/by the Chalukyas of Solanki or Nagabhata II of the Pratiharas in the 8th–9th century CE, possibly as a jeernoddhara of the existing shrine. This mandir was in active use till the dawn of the 11th century and had garnered the attention of people from all over the country.

The reputation of this shrine caught the attention of the Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni who descended upon it with great iconoclastic zeal and an insatiable lust for the treasure in 1026 CE. The people of Somanath hastened in regiments to the mandir and surrounded the Somanatha and fought with tears and cries for help, till more than fifty thousand were slain and the fort was conquered. Then Sultan Mahmud entered the mandir and when his eyes fell on the Linga; he broke it with the mace which he had in his hands. He took away a piece of the Linga to Ghazni, and with it paved the steps of Jami Masjid.[i] The blow dealt by Mahmud to the Somanath Jyotirlinga reverberates in the Hindu subconscious even today. The mandir was looted, desecrated, and finally put on fire following the orders of the Sultan. This was the first instance of an invader violently disrupting the worship of the Linga. An event that’s going to repeat itself like clockwork from hereon. The success party of Mahmud could not carry on for long, as the Paramara Emperor Bhoja along with his confederates rushed towards the mandir site with a huge army intending to avenge the Somanath Linga. Sultan made a hasty retreat to Multan through a spirit-crushing route along the Rajasthan desert under the constant harassment of the Jatts of Sindh, losing a lot of his resources all through the way.

Emperor Bhoja and Bhima I of the Solanki dynasty did not let the sadistic perverseness of Mahmud Ghazni stand in the way of worshipping the lord of the land, Somanatha. They consecrated a bigger Linga than the one Mahmud desecrated. A new pradakshina marga was created, sabha mandapa was extended and new steps were laid concealing the steps broken by Mahmud’s marauders. Bhoja along with Bhima rebuilt the shrine in such swiftness that within a few decades, Somanatha was viraajman in his abode with regular pooja taking place. This is known by the inscription of King Shashtha which records his visit to Prabhasa and performing a Suvarna Tula ceremony in 1042 CE.[ii]

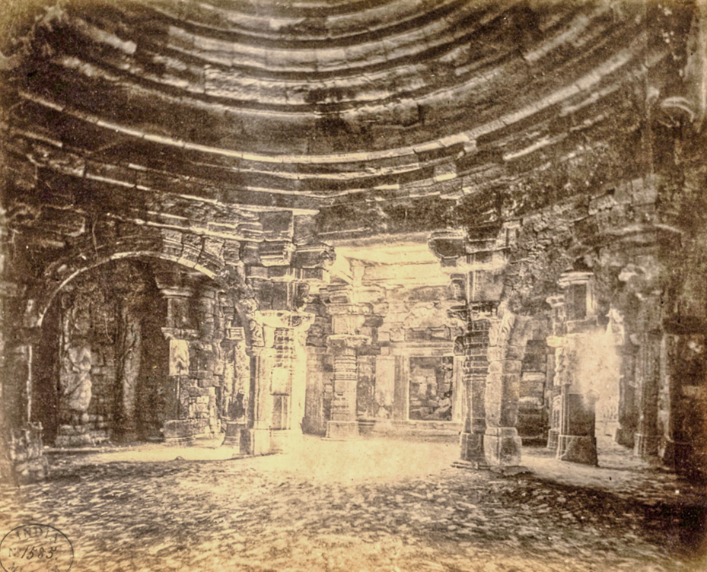

After close to 150 years of active worship, the mandir built by Bhoja was expanded and extended by Solanki King Kumarapala in 1169 CE under the instructions of guru Bhava Brihaspati. Built on the plinth of the fourth mandir, the sabha mandapa, garbagriha, and the pradakshina marga were expanded. A new gudha mandapa and entrances were added. Black basalt stone was used in the reflooring of the mandapa and the garbagriha. The Linga installed by Bhoja/Bhima I continued to be worshipped. White limestone found in the local mines was used for building the outer walls of the mandapas. By the time the renovation was done, the Somanath Mandir had a shikhara that was at least 9 storeys high. It was the desecrated ruins of this mandir that echoed the tales of a ghastly past to the arriving visitors in the 20th century.

How did the majestic mandir built by Kumarapala become a battered remnant of the haunting past over time?

For over a century following the establishment of the new mandir, the Solanki dynasty ably protected and governed the land of Prabhasa. Under their protection, Prabhasa flourished, gaining prominence as both a religious hub and a port city. Both the rulers and religious leaders of the land devoted themselves to the preservation and expansion of the mandir. This era marked a height of glory in the mandir’s history, that would not be witnessed again for many years to come.

Ruthless Alauddin Khalji ascended the throne of the Delhi Sultanate in 1296 CE, killing his predecessor/uncle Jalaludin Khalji. Even before he became the Sultan, Alauddin had laid waste to the Malwa countryside (1292 CE) and had conquered the impregnable Devagiri fort in the Deccan (1294 CE). After dealing with the Mongols in the first few years of his reign, he decided to annex the Saurashtra in 1299 CE. Contemporary texts like Prabhanda-Chintamani and Tirthakalpataru refer to Alauddin being invited to invade Gujarat by a minister of the Vaghela ruler Karna named Madhava, a Nagar Brahman. Dharmaranya, another contemporary text describes “how the wicked, graceless, and sinful minister Madhava, the blot on his family and the foe of his country, destroyed the rule of the Kshatriyas and established the rule of the mlecchas”[iii]

Kanhadade-prabandha provides a detailed description of this Khalji invasion. Alaf Khan and Nusrat Khan, both the generals of Khalji, captured the Vaghela Kingdom’s capital Patan, and converted the mandirs in the region to masjids. They continued to raid, loot, and pillage along the sea coast destroying many towns including Surat, and arrived at Prabhasa. The Rajputs mobilized their strength to protect the shrine of Somanatha and valiantly fought the enemy. But the fortress fell, and in front of the mandir, which they had vainly sought to protect, the heroic warriors, after ceremonial bathing and anointment, fell fighting, and surrendered themselves to Somanatha. Finally, Alaf Khan broke open the shrine, shattered the Somanatha Linga to pieces, and carried away the fragments in a cart to Delhi while saying “We shall make chunam (weighing stone?) out of it”.[iv]

Even though Alauddin’s generals damaged the mandir and broke the Linga of Somanatha, they failed to break the spirit and devotion of the Hindus as the mandir was again repaired by Mahipala, the Chudasama King of Junagadh. A new Linga was installed by his son Khengara, thereby restarting the worship sometime between 1325 and 1351 CE. But the glorious days of the shrine were already a thing of the past. Prabhasa was now under the rule of Islamic Delhi.

Khaljis were replaced by the Tughlaqs in Delhi and there are reports of an attack on Somanath by one of their governors in 1393 CE. A decade later, Mohammad Shah who was the then governor of Gujarat declared independence and became Gujarat’s first Sultan. His great-grandson Mahmud Begda became the Sultan in 1459 CE. He invaded the Junagadh in 1467 CE and made its ruler Ra Mandalik his subordinate. Two years later, Ra Mandalik declared his independence. In response, the Sultan attacked Junagadh and captured Ra Mandalik after a siege of two years, in 1471 CE. Even though Ra Mandalik embraced Islam, to further humiliate him, Mahmud Begda ordered the removal of the Linga from the Somanath Mandir and convert the edifice into a masjid. The dome and the minarets were probably added to the mandir structure during this conversion.

Yet again, Somanath proved to be the symbol of the resilience of the Hindus as within a few years of its conversion into a masjid, it was repurposed back as the Somanath Mandir. This effort was identified with the help of reddish-yellow stones/bricks that were used to replace the parts that were destroyed during the attacks. One such stone block had an incomplete inscription dated to Vikram Samvat 1647 (1590 CE).[v] During this phase of reconstruction, a new Linga was installed along with a new Brahmashila, and the level of garbagriha was raised. Unfortunately, the importance of Prabhasa Patan as a port declined after Begda’s attack and Surat rose to become a great entrepot.

Soon Saurashtra came under the rule of Mughal Emperor Akbar and Prabhasa saw a relatively peaceful period after centuries. But the peace did not last long. The great-grandson of Akbar, the religious fanatic Aurangzeb ascended the throne after imprisoning his father Shahjahan in 1658 CE. After consolidating his rule in Delhi, he proclaimed his infamous Farman of 1669 CE which destroyed the Kashi Vishwanath, Mathura Keshav Rai, and Somanath Mandir among many others.

“His Majesty, eager to establish Islam, issued orders to the governors of all the provinces to demolish the schools and mandirs of the infidels and with the utmost urgency put down the teaching and the public practice of the religion of these misbelievers”.[vi]

Even after that, Aurangzeb did not stop. In the words of historian Jadunath Sarkar, “Neither age nor experience of life softened Aurangzeb’s bigotry”.[vii] Because even as a defeated old man, living way past his prime with the Marathas, Sikhs, and Rajputs breathing down his neck, he orders,

“The mandir of Somanath was demolished early in my reign and idol worship there was put down. It is not known what the state of things there is at present. If the idolators have again taken to the worship of images at the place, then destroy the mandir in such a way that no trace of the building may be left, and also expel them (the worshippers) from the place”.[viii]

It thus appears that the Hindus had once again restarted the worship of Somanatha in the shrine after the attack in 1669 CE. But with this final call to desecration by Aurangzeb in the early 1700s, the pradakshina marga was destroyed, the structure was once again converted into a masjid by restructuring the Hindu pillars into arches, and a new white stone flooring was done to hide the Hindu elements of architecture in the structure.[ix]

From this point onwards, this mandir of Somanatha was no longer in use, and outside the fort of Dev Pattan (i.e. Prabhasa) by the side of the river Saraswati, a small mandir with a Linga was built, where pilgrims bound for Dwarka used to halt and pay homage.[x]

As Fate would have it, soon after the Somanath Mandir was destroyed for the final time, the rule of the Mughals in Saurashtra was put to the sword by the Maratha warriors led by Dhanaji Jhadav. K M Munshi aptly says “As soon as Aurangzeb silenced the mandir bells of Somanatha, the victorious shouts of ‘Har Har Mahadeva’ rent the skies of Saurashtra”.[xi] By the time of the 1760s, Saurashtra was completely in the hands of the Marathas. In 1783 CE, Queen Ahalya Bai, a prominent member of the Indore Holker family, discovered the ruins of Somanath in such a dilapidated state that restoration was deemed impossible. Consequently, she decided to construct a new shrine close to the original site.

The situation was so dire that the new Jyotirlinga was consecrated in an underground chamber to safeguard it from any potential future attacks. Meanwhile, a decoy Linga was placed in the larger garbagriha on the ground level.

The mandir established by Ahalya Bai Holkar has received active worship now for almost 250 years even though it has seen its fair share of troubles. The Nawabs of Junagadh repeatedly tried to make the life of Somanath pilgrims difficult by introducing various taxes, political pressure, and communal aggressiveness to the extent that attempts on the part of the Hindus from inside or outside the State to take an interest in the mandir were met with communal riots. It seemed that the mandir was destined to fall into a state of pitiful despair.

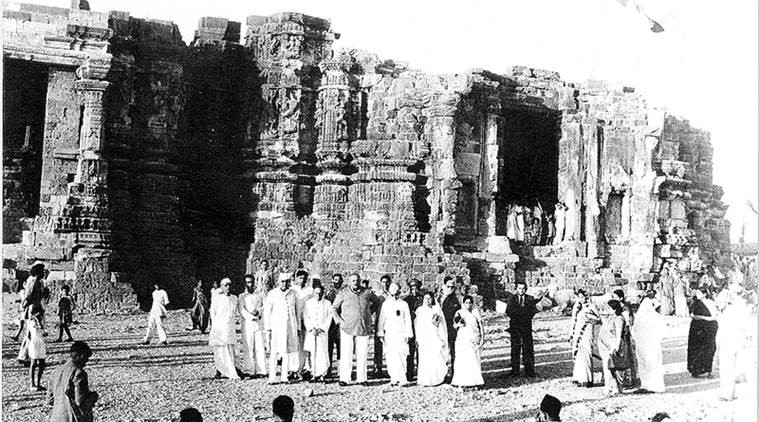

Fortunately, India gained independence from the British on 15th August 1947, and the state of Junagadh soon acceded to India. On 13th November 1947, on the day of Deepavali, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel visited Prabhasa and the Somanath Mandir. By then the old shrine which was converted to a masjid had an open mandapa, as the blocks of the mandir roof were removed to be used for the protection of the nearby Veraval port around 1838 CE. To add insult to injury, the erstwhile mandapa was used as a stable by the security guards.

On the same day, at a huge public meeting held at the Ahalya Bai Mandir, Sardar announced:

“On this auspicious day of the New Year, we have decided that Somanatha should be reconstructed. You, the people of Saurashtra, should do your best. This is a holy task in which all should participate”.[xii]

On the suggestion of Gandhiji, it was decided to not take any monetary aid from the Government of India for the resurrection of Somanath. By the end of 1949, twenty-five lakhs were collected and the construction of the new Somanath Mandir was underway with the demolition of the battered and pillaged ruins of the shrine built by Kumarapala which were damaged beyond the possibility of repair. The plan for the new mandir was drawn according to the same architecture as that of the previous Somanath Mandir.

The civilizational wounds dealt to the Hindu psyche by the hands of Mahmud Ghazni, Alauddin Khalji, Mahmud Begda, and Aurangzeb were healed by the power of time when Dr. Rajendra Prasad, President of India consecrated the Jyotirlinga on 11th May 1951. Sri Somanath Mandir raised its head with pride on 13th May 1965 with the booming of 21 guns announcing the rising of the flag on its shikhara at a height of 155 feet to mark the completion of its Kalasha Pratishtha.

The mandir of Somanath was destroyed by the invaders at least five times, the Jyotirlinga was cut to pieces and defiled in unimaginable ways on more than three occasions over the course of 700 years. Yet, even when their spirits were battered, even when the odds were overwhelmingly against them, the Hindus rebuilt the shrine and restarted the worship of Somanatha like clockwork. As the land of Ghazni which had once bathed in the riches looted from Somanath slid into a state of civil war and destruction in the 1970s, the land of Somanatha saw an unprecedented rise in its popularity and development showcasing the durability and strength of Hindu resilience.

The sacred land of Prabhasa, a place sanctified by the departure of Sri Krishna from his mortal form, where the revered Somanatha Mandir stands tall is a punyabhumi that continues to shine as a beacon of Hindu renaissance. The echoes of the past resonate in the present, as it was here that the landmark Ram Rath Yatra of the 1990s took its first step. This Yatra, organized by Bharat Ratna Lal Krishna Advani, aimed to reclaim the Ram Janmabhumi in Ayodhya. Advani saw the reconstruction of the Jyotirlinga Mandir on the rubble of loot and plunder as the first chapter in a journey to ‘preserve the old symbols of unity, communal amity, and cultural oneness’. He viewed the liberation of Ram Janmabhumi as the second chapter in this civilizational journey.[xiii]

Sources:

- Somanatha—The Shrine Eternal by K M Munshi

- History of Aurangzib Vol 3 by Jadunath Sarkar

- Massir-i-Alamgir translated by Jadunath Sarkar

- Mirat-i-Ahmadi by Gaekwad’s Oriental Series

Images: DALL-E (1st–4th temples), Wiki Commons (Archive

[i] Mirat-i-Ahmadi (Gaekwad’s Oriental Series 43), p. 119

[ii] Important Inscriptions from Baroda State, p. 71

[iii] Somanatha—The Shrine Eternal, p. 51

[iv] Ibid., p. 52-53

[v] Ibid., p. 90

[vi] Massir-i-Alamgir, p. 52

[vii] History of Aurangzib Vol 3, p. 268

[viii] Mirat-i-Ahmadi (Gaekwad’s Oriental Series 146), p. 313

[ix] Somanatha—The Shrine Eternal, p. 89, 121

[x] Mirat-i-Ahmadi (Gaekwad’s Oriental Series 43), p. 120

[xi] Somanatha—The Shrine Eternal, p. 57

[xii] Ibid., p. 67

Comments