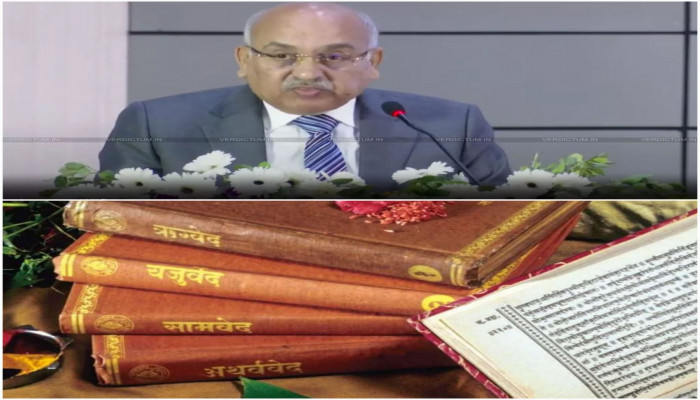

Vedas should be part of law school curriculum: Supreme Court Judge Pankaj Mithal

- In Reports

- 05:15 PM, Apr 15, 2025

- Myind Staff

Supreme Court Judge Pankaj Mithal said that law colleges and universities should start including ancient Indian legal thought from texts like the Vedas, Ramayana and Mahabharata in their curriculum. He stressed that students need to learn that ideas of justice and fairness are not just Western concepts but have deep roots in India’s traditional legal philosophy.

“It is time that our law schools formally incorporate the ancient Indian legal and philosophical traditions into the curriculum. The Vedas, the Smritis, the Arthashastra, the Manusmriti, the Dhammas, and the epics of the Mahabharata and Ramayana are not merely cultural artefacts. They contain deep reflections of justice, equity, governance, punishment, reconciliation and moral duty. Their duty is indispensable if we are to understand the roots of Indian legal reasoning,” he said while speaking at a legal conference held at the National Law Institute University in Bhopal on April 12, which was organised to celebrate 75 years of the Supreme Court.

The judge mentioned that steps are being taken to make the country’s judicial system more in tune with Indian culture. One such step is the translation of Supreme Court judgments into regional languages for broader accessibility. As part of this initiative, during former Chief Justice DY Chandrachud’s tenure, a new statue of the Lady of Justice was introduced, dressed in a sari, holding a book instead of a sword, and without the traditional blindfold.

The book referred to is the Constitution; however, Justice Mithal suggested having four separate books instead, “Along with the Constitution, there should be the Gita, Vedas and Puranas. That’s the context in which our legal system should work. Then I believe we will be able to provide justice to each citizen of our country.” He also suggested that law colleges and universities introduce a new subject titled “Dharma and Indian Legal Thought” or “Foundations of Indian Legal Jurisprudence.” This course, he said, shouldn't just involve reading texts but should explore how traditional Indian concepts of justice relate to and influence modern constitutional principles. “Such a subject would not only provide students with cultural and intellectual grounding but also help shape a uniquely Indian jurisprudential imagination.”

Again, he explained, “Imagine a generation of lawyers and judges who understand Article 14 not just as a borrowed principle of equality but also as an embodiment of Samath (equality), who view environmental law not just through statutes but through the reverence for Prakritik (nature) in the Vedas, who understand alternate dispute resolution (ADR) as a continuation of Panchayat traditions contained in Shastras and Manusmriti, and who grasp constitutional morality as a modern articulation of ancient Rajdharma.” The judge further emphasised that this project isn't about nostalgia by saying, “It is a project of rooted innovation. This curriculum reform would serve a deeper constitutional goal – the preservation of India’s pluralistic legal identity. It would reinforce the idea that Indian Constitutionalism is not merely an import but a living constitution of a civilizational legacy.”

Reflecting on the Supreme Court’s 75-year journey, he noted that even as the world grapples with “rising inequality, rapid technological change and developing polarisation,” the Court has stood as a stabilising institution by upholding the rule of law.” However, he emphasised that “ the story of Indian justice does not begin in 1950. It is rooted in something more ancient, yet remarkably enduring.”

He pointed out that the Supreme Court’s motto, Yato Dharmaso Tatho Jaya (where there is Dharma, there is victory), comes from the Mahabharata. According to him, “Justice, in our civilisational understanding, is an embodiment of dharma - a principle that encompasses ethical conduct, social responsibility and the rightful exercise of power.” In his view, the Court’s responsibility “is to ensure that constitutional morality triumphs over executive expediency, that justice is not sacrificed to political convenience and that the rule of law is not rendered to a rule of power.”

Emphasising the Supreme Court’s rulings on environmental protection, the judge noted that the Atharvaveda urges people not to harm the sky, earth, air, water, or forests. Speaking on equality, the judge cited the Rig Veda, which teaches that no one should be seen as superior or inferior, as all are brothers journeying along the same path. The judge explained that Dharma existed long before the concept of law, and while Western legal systems often separate law from morality, ancient Indian jurisprudence saw Dharma as a guiding force that combined righteousness, justice, duty, and harmony. He added, “The Supreme Court’s work often mirrors this unity of legal rule and moral vigil.”

Comments