Right to Information (Amendment) 2019: What does the Amendment actually propose? And why the opposition 'outrage' is misplaced.

- In Politics

- 05:56 AM, Aug 11, 2019

- Aishwarya Hariharan

India brought major amendments to the Right to Information Act in parliament last month. On 22 July 2019, the Rajya Sabha passed the Right to Information (Amendment) Bill, 2019 by a voice vote wherein the opposition staged a walkout during the vote. The Lok Sabha passed the Right to Information Amendment Bill, 2019 through a voice vote with 218 votes in favour and 79 against. The legislation was passed after the opposition’s proposal to send the Right to Information Amendment Bill to select committee was defeated with 117-75 in the Rajya Sabha. On 1st August 2019 the President of India assented to two key amendments in the country’s Right to Information Act.

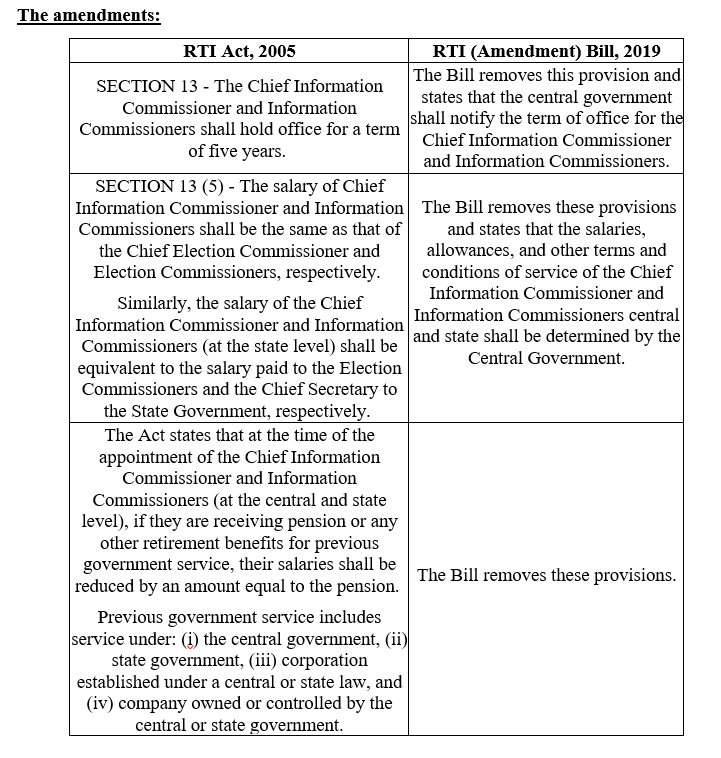

The amendment bill proposed an amendment in Right to Information Act, 2005 so as to provide that the term of office, salaries, allowances and other terms and conditions of service of the Chief Information Commissioner and Information Commissioners as well as the State Chief Information Commissioner and the State Information Commissioners, shall be such as may be prescribed by the Central Government.

The existing law was introduced with the sole objective of empowering people, containing corruption and bringing transparency and accountability in the working of the Government. This was initiated by the Ministry of Personal, Public Grievance and Pensions to ensure a portal for citizens who searched and needed quick access to any information. The law states that public authorities are required to make disclosure on various aspects of their structure and functioning. Every public authority is obligated to maintain computerized versions of all records as softcopies in such a way that it can be accessed over a network anywhere in the country and issued to the person who has requested for information.

Therefore, under this act Public authorities are required to disclose their functions, financial information and duties. According to Section 2 (h) "public authority" means any authority or body or institution of self- government established or constituted-- (a) by or under the Constitution; (b) by any other law made by Parliament; (c) by any other law made by State Legislature; (d) by notification issued or order made by the appropriate Government, and includes any-- (i) body owned, controlled or substantially financed; (ii) non-Government organisation substantially financed, directly or indirectly by funds provided by the appropriate Government.

The Central Information Commission is headed by Chief Information Commissioner and such number of Central Information Commissioners, not exceeding ten, as may be deemed necessary as per Section 12 (1) of Right to Information Act, 2005. They are appointed by the President for a fixed tenure of five years and a salary of the rank of the Chief Election Commissioner and Election Commissioners respectively.

As per Section 12 (3) which deals with the appointment of Information Commissioner has not been interfered in any way in the Amendment. The present amended law seeks to amend Section 27 of Right to Information Act 2005 in order to frame rules for the tenure and terms of conditions for Information Commissioners, which was not framed earlier in Right to Information Act 2005. As per Right to Information Act 2005, Chief Information Commissioner is equal to Chief Election Commissioner and thereby equal to Supreme Court Judge. Similarly, the State Chief Commissioner is equal to Election Commissioner and thereby equal to Supreme Court Judge. This itself is an anomaly, considering the fact that Election Commission and Supreme Court are constitutional bodies.

The other contradiction is that Chief Information Commissioner and State Information Commissioners enjoys the status of Supreme Court Judge but the verdict passed is liable to be challenged in the High Court. The opinion to bring in this change did not subjectively originate from the government alone but also held by several sections of society and judiciary. In Rajiv Garg vs Union of India MANU/SCOR/8501/2013, the Supreme Court directed that decisions be taken on uniformity of service conditions of various tribunals. Similarly, the second reform commission in 13th report of April 2009 also recommended that there is need for greater uniformity in service conditions. Besides, the Right to Information Act has not given the government any rule-making powers. The present amendment is an enabling legislation which will authorize the government to frame the rules by amending Section 27 and deliberate upon the terms of services of Central and State Information Commission through Section 13 and Section 16 of the Right to Information Act 2005 respectively.

Most importantly, Section 4 of Right to Information Act is implemented wherein suo moto information is now available on all the government websites even without having to file an Right to Information to seek information. Therefore, this Amendment does not tend to compromise independence of the 2005 Act or directly touches upon the autonomy of the Act so far as understood.

The current government has focused on the principle of ‘maximum governance, minimum government’ wherein the Government has introduced various such initiatives like abolition of interviews, self-attestation etc. These initiatives are mainly aimed at citizen-centric approach of the government. If we take a good look at this approach we will understand that most of the information is available in the public domain itself. As per Act 2005, the power of framing rules concerning Information Commissions does not fall under either the Union or the State or the Concurrent lists. It automatically falls under the residuary powers of the Central Government. Therefore, the amendment will provide the Central Government with the right to employ, decide the term, allowance and conditions of service of the Information Officers.

.png)

Comments