Re-Examining The Legacy of Charles Dickens

- In History & Culture

- 06:23 PM, May 17, 2020

- Sai Priya Chodavarapu

Charles Dickens, known for his equalizing and charitable view of British society in his widely acclaimed literary works, exhibited an overt contempt for Indians and other non-white native populations in general, a fact that is often overlooked while discussing the man’s legacy.

Dickens wrote, in a letter to Emile de la Rue on 23 October 1857, immediately following the Indian Mutiny of 1857:

“You know faces, when they are not brown; you know common experiences when they are not under turbans; Look at the dogs - low, treacherous, murderous, tigerous villians"

“I wish I were Commander in Chief over there [India]! I would address that Oriental character which must be powerfully spoken to, in something like the following placard, which should be vigorously translated into all native dialects, “I, The Inimitable, holding this office of mine, and firmly believing that I hold it by the permission of Heaven and not by the appointment of Satan, have the honor to inform you Hindoo gentry that it is my intention, with all possible avoidance of unnecessary cruelty and with all merciful swiftness of execution, to exterminate the Race from the face of the earth, which disfigured the earth with the late abominable atrocities".

Source: Kathleen Mary Tillotson and Graham Storey, The British Academy/The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens, Vol. 8: 1856–1858 or can be found at https://www.oxfordscholarlyeditions.com/view/10.1093/actrade/9780198126621.book.1/actrade-9780198126621-div1-838

Charles Dickens, in a letter to Baroness Burdett-Coutts on 4 October 1857, expressed a similar sentiment:

"I wish I were Commander in Chief of India. The first thing I would do to strike that Oriental race with amazement (not in the least regarding them as if they lived in the Strand, London, or at Camden Town), should be to proclaim to them in their language, that I considered my Holding that appointment by the leave of God, to mean that I should do my utmost to exterminate the Race upon whom the stain of the late cruelties rested; and that I begged them to do me the favor to observe that I was there for that purpose and no other, and was now proceeding, which all convenient dispatch and merciful swiftness of execution, to blot it out of mankind and raze it off the face of the earth."

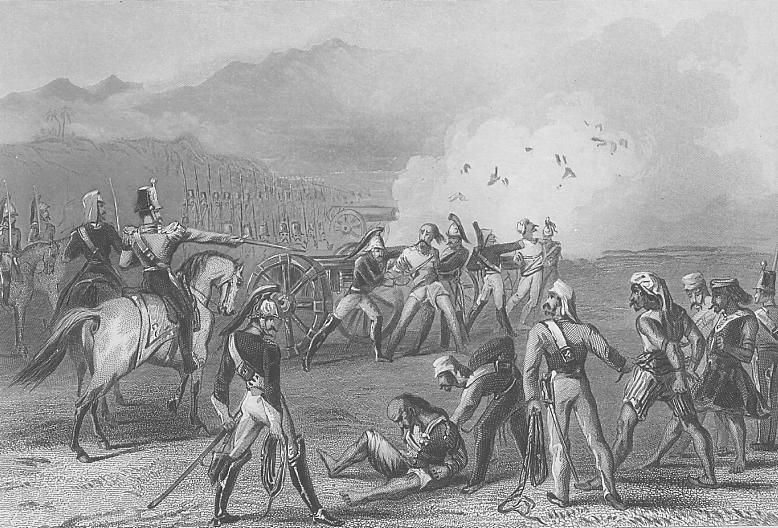

Dickens also called for the "extermination" of the Indian race and applauded the "mutilation of the wretched Hindoo” who were punished by being "blown from...English guns[s]" -- From "The Speeches of Charles Dickens", K.J. Fielding, Ed., Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1960, p. 284

– referring to the practice of execution by blowing from cannons, wherein the man is tried to the mouth of a cannon and then it is fired, a method of killing practiced by Mughals, British, and Portuguese in their colonies. During the British Raj, destroying and scattering the bodies of Hindus by explosion also served the purpose of effectively preventing the performance of a Hindu’s last rites, which would torture Hindu souls beyond the grave. In some cases, an improper execution would result in the man being amputated, and hanging in agony to the cannon, while a British soldier used a gun to finish him off.

Source: The Advocate of Peace, Boston Peace Society; January and February 1857 edition, British Retaliation in India pg 23-24

Execution of mutineers by blowing from a gun by the British, 8 September 1857.

To lend some context, these letters were written by Dickens immediately after the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, following which The Times and other British newspapers began to spread anti-India propaganda, depicting sensationalized “eyewitness accounts” of British women and girls being raped by Indian rebels. These greatly exaggerated accounts of crimes by Indian rebels triggered mass anti-Indian hysteria amongst the British public and the soldiers posted in India. Though the painting of Indians as "dark-skinned rapists" was commonplace even before the mutiny, the depiction of natives as savages that needed to be “civilized” and suppressed, along with the rumors surrounding the mutiny perpetuated this racial stereotype even further - making British troops that much more bloodthirsty.

The 93rd Highlanders Clearing of the Secunderbagh before Lucknow

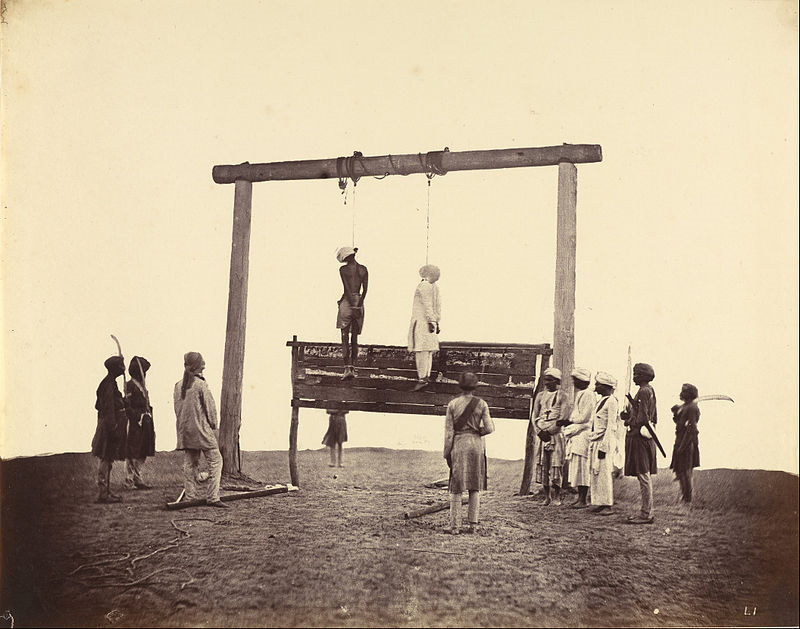

Back in India, the resultant large-scale massacres of Indians by British troops seeking revenge were devastating. Mass executions were carried out across the country, at Lucknow, Kanpur, Peshawar, Allahabad, Firozpur etc. In Oudh, around 150,000 Indians were butchered by British forces, of which 100,000 were innocent civilians. Delhi was annexed and ransacked, with rampant, unnecessary violence and vandalism. At Kanpur, mutineers were hung to death, blown from cannons, Muslim or Hindu rebels forced to eat pork or beef, and forced to lick buildings freshly stained with blood of the dead before public hangings. Practices of torture included "searing with hot irons, dipping in wells and rivers till the victim was half suffocated, sequencing the testicles, putting pepper and red chilly in the eyes or introducing them into the private parts of men and women, prevention of sleep, nipping the flesh with pinners, suspension from tree branches, imprisonment in a room used for storing lime..."

(R. Mukerjhee. Spectre of Violence: The 1857 Kanpur Massacre, New Delhi 1998. p. 175)

The hanging of two participants in the Indian Rebellion, Sepoys of the 31st Native Infantry. Albumen silver print by Felice Beato, 1857

'Never before and never after in the history of British rule in India was there violence at the level that 1857 witnessed.'

Rudrangshu Mukherjee for Business Standard

Yet, according to Dickens, these brutalities of the empire were all completely justified, since Indians were the vilest of creatures, uncivilized savages, blamed for the uprising that resulted in the death of a few hundred Brits, who were unwelcome guests in India, might I add.

Dickens’ explanation for the mutiny was an unjust reduction of the religiously and politically motivated uprising to yet another instance of “Oriental treachery”, as seen in many of his articles. For instance, one of them, published in his weekly, titled “Hindoo Law”, describes the “savage cruelty” of the “seemingly mild” Hindus, which had broken out like a “long smoldering flame”. His narrative of the revolt was consistently limited to representing the mutineers as rapists and the Englishmen as the chivalrous defenders of the imperiled female virtue.

Source: Unequal partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, and Victorian authorship by Nayder, Lillian

Although the Indian race was only fit for extermination, he did not hold back in investing in and profiting off of the Indian Railway. In 1868, he owned shares in the Great Indian Peninsula Railway Company, worth £3,000 (£310,000) and generating about 5%, about £15,500 in today’s currency. (The British government guaranteed investments in Indian railways at the time.)

Dickens was also proponent of slavery and was also anti-Italian, anti-Irish, anti-Zulu, anti-Indian and anti-Native American, anti-Innuit, and anti-Semite.

In 1849, Dickens wrote to a friend discussing a prospective article to in his literary weekly Household Words that would discuss “a history of savages, showing the singular respect by which all savages are like each other; and those in which civilized men, under circumstances of difficulty, soonest become like savages.”

In 1868, in a letter discussing the uneducated black population being given voting rights in the US, Dickens railed against "the melancholy absurdity of giving these people votes", which "at any rate at present, would glare out of every roll of their eyes, chuckle in their mouths, and bump in their heads."

Dickens’ reaction to the massacre of Jamaicans, ordered by the island’s governor, Edward John Eyre, who unleashed a brutal crackdown on the rebellion in 1865 and also showed his wrath upon the general black/colored population, was also not out of character. The grisly statistics of the outcome were “439 dead, six hundred flogged and 1,000 houses burned” - racial vengeance at its worst. When news reached London, many British luminaries at the time wished to try General Eyre for his atrocities, including included Charles Darwin, Thomas Huxley, and even “survival of the fittest” proponent Herbert Spencer; together known as the Jamaica Committee. They were, by no means anti-racism or anti-imperialist by simply objected to the use of martial law to decree murders. In contrast, other elite Victorians immediately sprang to Eyre’s defense, and formed the Eyre Defense Committee that included Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, Charles Kingsley, Alfred Lord Tennyson and Charles Dickens. Thomas Carlyle chaired the Eyre Defense Fund, to raise £10,000 for the costs of legal representation for the governor. Their collective belief in racial superiority led them trust a white governor’s judgment and doubt the trustworthiness of people of African descent. In the end, Eyre was acquitted, because it was said that his crimes involved “only negro blood”.

An illustration of the Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica

One of the reasons why Dickens’ racism is so shocking to many is the seemingly strong moral compass evident in his body of work. Much of his work explored the themes of social justice and poverty, in the context of discrimination due to the class system in newly industrializing England. He never shied away from describing the seedy underbelly of Victorian London, and the squalor and abject poverty of the lower classes. This is admirable, and one might even say path-breaking due to the fact that much of British literature at the time was remarkably elitist. But the contradiction between the Dickens’ empathy for the working class in industrial England and the Dickens that spoke, wrote of, and supported the vilest descriptions and actions on blacks, Indians and natives is stark.

Although he was born poor, he managed to complete his education, and by age 20 in 1832, he was an ambitious young man that sought fame and started a career as a writer. By 1836, he gained literary acclaim, with the publication of The Pickwick Papers. He achieved great success and recognition during his lifetime, an honor denied to many artists and writers of the time. His estate grew along with his formidable success. By 1869, Dickens’ investments totaled a whopping £20,000, equivalent to more than £2m today, and he would have received 3% p.a in income – about £600 (£62,200). Over two hundred years after his birth, the Dickens intellectual properties continue rake in a whopping £280 million per year for the UK economy.

His reputation as a Victorian social reformer stood in stark contrast to his “dark” side – which held utmost contempt for the colonized world. His blatant call for the culling of all non-white populations, with a special distaste for Indians, as they “dared to revolt”, is sadly, not sufficient to prevent Indians today from eulogizing the man.

Read the News18 coverage of Dickens’ bi-centennial celebrations, and English professors at Indian universities praising Dickens.

https://www.news18.com/news/books/india-celebrates-200-years-of-charles-dickens-444111.html

Be it due to ignorance or deliberate suppression of the dark truth, it says a lot about India’s ability to forgive and forget, as none of the things Dickens said about Indians are widely known in India, although they should be; just as the other atrocities of colonial rule are largely suppressed – scarcely written in history books, and whitewashed by our own historians.

What sets Dickens apart from other racists of the time, since one might argue that racism was “natural” and socially accepted? After all, it is unfair to apply today’s moral standards to a society that is almost two centuries old.

What sets Dickens apart from other racists of the time, since one might argue that racism was “natural” and socially accepted? After all, it is unfair to apply today’s moral standards to a society that is almost two centuries old.

Firstly, Dickens was objectively more hateful and racist than the average racist, even compared to what was typical for the time. It takes a special sort to wish for genocide of entire races, not just Indian but aborigines, blacks and other non-whites. While some of his racist tendencies can be chalked up to the rampant propaganda and white/colonial supremacism, his political opinions were even more so perilous as they were all frequently in print.

Dickens ran two weekly publications, Household Words and All the Year Round, where he frequently published racist opinions, both his own and those of other writers. Samuel Sidney, who wrote for Household words, wrote many articles about Australia and the aboriginals, and believed that if it was difficult to gun down the aborigines, poison might to the trick (Lansbury, 64). Dickens’ published works and magazines had considerable influence upon British society as the goodwill he enjoyed extended to the literary world. This is precisely why his racism is even more abhorrent – his position as a wealthy, successful writer afforded his opinion more credibility and reach across Britain, and overseas, in the United States.

From: Rule of Darkness: British literature and imperialism, 1830-1914

by Patrick Brantlinger

At this juncture, it is important to note that many of his literary contemporaries did not all share the same level disgust for native races.

A fitting example is Wilkie Collins, with whom Dickens frequently collaborated, who notably lacked the same hostility towards Indians. The two frequently disagreed when it came to political opinions, and this reflected in their work. Collins did not fault Indians for the Sepoy mutiny to the same extent as Dickens, knowing that much of the coverage of the mutiny within British news was biased, and simply untrue. In Collins's own work A Sermon for the Sepoys, he appeals to the Indian mutineers using references from an Indian sacred text, not a Christian one – citing “Oriental literature” as being abound with “excellent moral lessons” and disassociates himself from Dickens's desire to exterminate the Indian race. In their collaborative novella for the Christmas edition of Household Words, “The Perils of Certain English Prisoners”, Collins reminds readers that the mutiny was caused, in part due to the indulgence in excesses by British officers who abused their Indian subordinates. He suggests that working class Brits may have more in common with the native rebels than Dickens lets on. However, throughout the text, it becomes increasingly apparent that Dickens and Collins use Christianity as the means of perpetuating the mindset of racial superiority, thereby suggesting that the ideologies of religiosity and racism are inextricably linked. In Collins' novel The Moonstone, he says that it is the Indians that were actually on the defensive during the mutiny, not the British, contrary to the impression given by the British press.

[Source: Lillian Nayder, in her book Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, and Victorian Authorship, describes the strained relationship between Dickens and his co-author Wilkie Collins.]

For someone so committed to social justice, it is surprising that the same Christian ideals don’t extend to fellow human beings of other races, or even people of the same race, the “barbaric” Irish and Italians; but at least he didn’t call for their extermination.

Why are Dickens’ racist rants important, so long after he is dead and gone?

First, a disclaimer: If one is able to separate the man from his literature, then it is entirely left to one’s personal choice whether to read his work or not. I am not against purchase, reading, or dissemination of his work, but lionizing the man in Indian school syllabi is wholly objectionable, for many reasons:

- Dickens is a British institution – statues of him are scattered all over Britain, libraries, memorials and museums are named after the man. On the other hand, we are a former British colony, struggling to rebuild our nation after the endless brutalities inflicted upon us, and still reeling from the damage done to our economy, our spirit, and our unity. As much as I appreciate progressive thought, must India be such a meek pushover that we regard their racist writers with such high praise? I don’t object to reading other not-so-racist British authors, but when it comes to Dickens, I’m afraid India must draw a line, for her own sake. Why don’t we simply leave the reading of his work to those with personal interest or those undertaking an advanced or doctoral study? If we wish to continue teaching Dickens to school children, we must also be willing to put his work into historical perspective. De-colonizing our school syllabi is a step closer to de-colonizing our mentality and rebuilding self-esteem.

- Purchasing and reading/watching any adaptations of Dickens’ work contributes to UK economy. Is this not a form of neo-colonialism?

- There are hundreds of writers that can be given recognition that perhaps they were denied, in lieu of Dickens, be it Indian writers that wrote in English or Indian writers that wrote masterpieces in Indian languages, that school children have hardly ever heard of. Aren’t we doing a great disservice to India’s literary and artistic legacy?

- Racism isn’t restricted to Dickens, nor to Dicken’s era:

One can contest that “the times were different” in the late 1800s, and so was the perception of racist opinions. But what then, explains the presence of racists in today’s society? A whole 200+ years later, and we’ve only succeeded in lessening the degree and openness of racism but we cannot honestly say that racial discrimination and opposition to multi-cultural societies doesn’t exist, especially in England.

“Wherever her sovereignty has gone, two blades of grass have grown where one grew before. Her flag wherever it has been advanced has benefited the country over which it floats; and has carried with it civilization, the Christian religion, order, justice and prosperity. England has always treated a conquered race with justice, and what under her rule is the law for the white man is the law for his black, red and yellow brother.”

Wells, David A. “Great Britain and the United States: Their True Relations.” The North American Review, vol. 162, no. 473, 1896, pp. 385–405. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25103690.

David Wells’ fantastically misinformed opinion sums up the current attitude of the majority English towards colonization*, as the propaganda has been wildly successful. Modern brits truly believe, even in 2020, that England “civilized the heathens” and introduced them to English education and “Christian values”, which is, in their mind, a favor done to the savage Indians out of their benevolence.

Similarly, Niall Ferguson in his 2003 book Empire, says that British imperialism gave to the world its admirable and distinctive features (language, banking, representative assemblies, the idea of liberty) and that India, “the world’s largest democracy, owes more than it is fashionable to acknowledge to British rule”.

Must we play into the hands of modern-day racist attitudes of Britons that condone the atrocities committed by colonial era Britain?

While Dickens undoubtedly may have been a great writer, is it justified for a former colony to ignore his views about our country and its history, especially when this controversial figure is exalted to the status of a literary great? Whatever the answer may be, we must contemplate the gravity of his opinions and their relevance, within a framework of historical context. We owe it to posterity to present a well-rounded, truthful picture of the man, when presenting his life and works.

Footnote:

*Almost 60 per cent of Britons were proud of the British Empire and almost 50 per cent thought it had made the colonies better off, according to a YouGov poll in 2014. Brits’ refusal to acknowledge colonial atrocities is a manifestation of what the British historian and academic Paul Gilroy describes as “postcolonial melancholia”, in his book After Empire, written in 2004.

Further reading/references:

- The Imperial Context of "The Perils of Certain English Prisoners" (1857) by Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/dickens/pva/pva354.html

- Jamaica’s Morant Bay Rebellion: brutality and outrage in the British empire.

- I didn’t go into much detail about the numerous racist remarks made about non-Indian natives in both his published work and private letters, so anyone interested in investigating further may find a compilation at: “Dickens and Racism”, which includes citations. http://www.estherlederberg.com/EImages/Extracurricular/Dickens%20Universe/Racism%20in%20Dickens.html#1BACK

- The other darker Charles Dickens

- Stereotypes of Indians in 19th-20th century British literature https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stereotypes_of_South_Asians#Great_Britain_and_English-speaking_territories

- Dicken’s relationship with copyright law goes at least as far back as his first serialized novel, the Pickwick Papers, which he completed in 1837

- The Dark Side of Dickens

- Why Charles Dickens was among the best of writers and the worst of men, by Christopher Hitchens, May 2010 https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2010/05/the-dark-side-of-dickens/308031/

- Dickens’ Estate

- Unequal Partners : Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, and Victorian authorship by Nayder, Lillian https://archive.org/details/unequalpartnersc00nayd

- Not All R & R is Good: Religiosity and Racism Within Charles Dickens’s and Wilkie Collins’s The Perils of Certain English Prisoners https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1309&context=studentpub

Comments