Rajasthan must not lose its momentum in water management

- In Current Affairs

- 11:34 PM, Mar 23, 2022

- Sahana Singh

The Indian state of Rajasthan has always been known for its exquisite history and culture. But it is also known for its management of limited water resources with 60% of its land classified as desert. A visit to any of the villages in the deserts of Rajasthan will give insights into the reducing, reusing, and recycling measures for managing water resources that have been a part of the culture long before the 3Rs were coined.

In December 2021, however, I got the chance to visit an entirely different part of Rajasthan; the non-desert portion in which there is more rainfall than one would imagine in a state that is on the whole, water-deficient. And yet, this part of Rajasthan has been losing its groundwater at a rapid pace due to a lack of proper planning, as well as a lack of community participation in harvesting rainwater which is simply draining away as runoff. As we know, when rainwater just flows away unchecked without being collected, even a place like Mawsynram in eastern India, which receives the highest rainfall in the world, can face water shortages.

In 2016, the Chief Minister of Rajasthan, Vasundhara Raje ji belonging to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) launched a massive program to tackle the water shortages in the state. Called ‘Mukhyamantri Jal Swavlamban Abhiyan’ (MJSA) the program set a near-impossible target of making all villages across Rajasthan self-sustainable in terms of water availability for drinking and irrigation. In order to achieve this, she took the help of Sriram Vedire, a dynamic person who had moved back to India after spending 15 years in the US. Sriram ji’s work in the water sector had already been noticed by the Ministry of Water Resources, River Development, and Ganga Rejuvenation and he had been appointed Advisor to the Ministry in 2014.

The Chief Minister (CM) of Rajasthan gave him full charge of implementing the program she had envisioned, a job that Shri Vedire took very seriously. As he writes in his book “A Distinctive Water Management Story — The Rajasthan Way”, the CM wanted “a permanent and long-lasting solution to the water crisis of the state instead of an ad hoc solution to temporarily fix something”. Vedire ji made the blueprint ready for her by the time she won elections and took office in December 2013. From what I could research online, it seemed to me that the program had been a tremendous success and even a usually critical media had heaped accolades on the impacts.

Knowing that I would soon be visiting Rajasthan, I took the opportunity to meet Sriram Vedire ji at his office in the Ministry in New Delhi to get an overall perspective of the work done in the state. The party in power has changed in Rajasthan and Shri Ashok Gehlot of the Indian National Congress party took office as Chief Minister in December 2018. I wondered if the ball that had been set rolling under Vasundhara ji’s stewardship was still moving forward. Sriram ji indicated to me that the very name of the program had now been changed to Rajiv Gandhi Jal Sanchay Yojana. What became apparent to me was that during his stint, Vedire ji had set up mechanisms for different departments concerned with water to collaborate and quickly implement decisions. One can imagine how important this is when there are so many crosscutting departments that are involved with water such as Water Resources Department, Agriculture Department, Horticulture Department, Panchayat Raj Department, Rural Development Department, Public Health Engineering Department, Watershed and Soil Conservation Department, and more! Vedire ji had incorporated both a top-down as well as bottom-up approach in planning. Even non-governmental organizations and external aid organizations had all been factored in along with the government departments in a very systematic manner. All river basins in Rajasthan had been studied in depth to know surplus and deficit basins. A state water grid had been designed which was digitalized, touchscreen-driven, and could give information right down to the Gram Panchayat level. A GIS platform was used and geo-tagging, as well as electronic monitoring, were done for the first time in the state. Every structure and activity was geo-tagged. Even the money that came in via donations was geotagged to the structure it was spent on so that there was full accountability.

I could not wait to visit Rajasthan and check out at least a few developments that Sriram ji had mentioned. Our first stop was at Jodhpur where we spent one night. On the next day, as soon as my husband and I completed an unforgettable trip to our Kuldevi temple at Nadol in southern Rajasthan, we traveled further south through the narrow, hilly roads in Udaipur District. We had already taken an appointment to meet people from the Watershed and Soil Conservation Department of Rajasthan Government in a place that fell under the jurisdiction of Saayra Panchayat Samiti in Udaipur District. The landscape became distinctly greener as we moved closer to Udaipur and innumerable pools of water nestling in the midst of rocks became visible. Unable to find the exact meeting point on our GPS, we decided to wait near a temple until the engineers located us. It was a beautiful Devi temple and I was glad to find the time for a quick darshan and to soak in the cool, salubrious climate. There was no one inside the temple except the priest who was himself sweeping it clean.

The engineers led by Shri Vijendra Agarwal located us soon and we began to follow their car. The variety of rainwater harvesting structures that can be built, the process of designing and constructing them, the huge task of maintaining them — all these became apparent as we visited one site after another.

Vijendra ji showed us an anicut in Saayra and explained how it was storing rainwater. It took me back to my civil engineering days when I had studied them as check dams. They were constructed across small streams to impound water and to recharge the groundwater as well as to create some storage that could be used for irrigation and various purposes. What I have come to know now is that the word ‘Anicut” used by the British colonizers was actually a distorted version of the Tamil and Kannada word Aanekattu. Of course. There was a great deal of civil engineering knowledge that the British picked up from Indian engineers especially in southern India. You will find more leads about this in my book. Even today, there are a staggering number of engineering colleges in southern India which attract students from all over the country.

Next, Vijendra ji took us to a breathtakingly beautiful place which could well have been a location for a Bollywood song. There were strange-looking trenches at periodic intervals which the engineers only referred to in acronyms like CCT, ST, and MPT. These were Continuous Contour Trenches, Staggered Trenches, Mini Percolations Tanks amongst others.

The main thought behind all these rainwater harvesting and groundwater recharging structures was to stop rainwater from gushing away and instead, to slowly percolate into the soil until it reached the aquifer. Had there been enough forest cover, this percolation would have happened naturally. Hence, afforestation is also one of the measures being undertaken at various places in Rajasthan. The roots of plants and trees bind the soil to the ground which also helps to hold rainwater. Some 13.8 million saplings have been planted in over 12,000 villages across the state. The water table has risen considerably in all the places where the water recharging structures are being maintained. Thanks to the extra water, many farmers were growing an extra crop or two, which was increasing their family incomes.

The Ridge-to-Valley approach was a term that came up frequently. Starting from the first-order streams in the ridges to the second, third, and further order streams in the valley, appropriate structures and activities had been planned that combined both hi-tech tools and traditional water conservation technologies. This was an extension of the concept of Integrated Water Resources Management which is being promoted internationally for the past several decades. The sun was setting and the magic of twilight we experienced in Saayra will stay with us for a long time.

We stayed the night in a small no-frills hotel in the outskirts of the famed city of Udaipur. It was decided that we would not visit any of the famous palaces and forts that Udaipur is known for. We would make a separate trip to see them and explore in detail. There was only a half-day available before we needed to start for Jodhpur so we only wished to see a few of the modern as well as historical rainwater harvesting structures being maintained by the Rajasthan government. Shri Atul Jain, the Superintending Engineer of Watershed and Soil Conservation Department of Rajasthan Government had asked us to meet for morning chai at a Dhaba. It was a delight to chat with him on various matters related to water management.

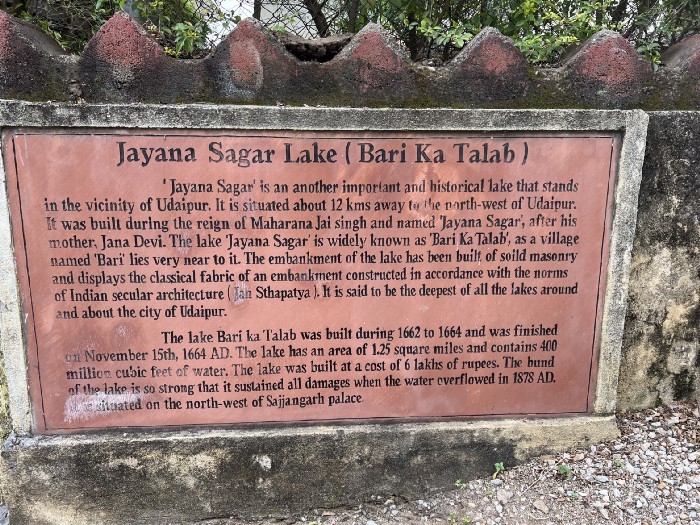

Next, we were taken by Shri Jitendra Chordia, Assistant Engineer to see ‘Bari ka Talab’, a historical lake built in the 17th century by Maharana Raj Singh I in the memory of his mother Jana Devi. A vast expanse of water stretched out before us giving a sense of assurance that we were not running out of this life-giving resource just yet. I marvelled yet again at how even just a few centuries ago, the level of aesthetics was so much higher than it is today. Beautiful chhatris (canopies) offered space for picnic spots and to admire the waterscape.

Unfortunately, the information about the place inscribed on a wall was incorrect. It said the structure was built by Maharana Jai Singh which was wrong. Sadly, despite requests to correct it by members of the Udaipur chapter of INTACH, the wrong signage continues to be on display. The wheels of Indian bureaucracy continue to be stuck in the mud of lethargy. I wondered why the term “secular architecture” was used to translate Jan Sthapatya. The whole distinction between secular and religious was a colonial construct and hardly applicable to Hindu frameworks in which there was never a fight between religion and science.

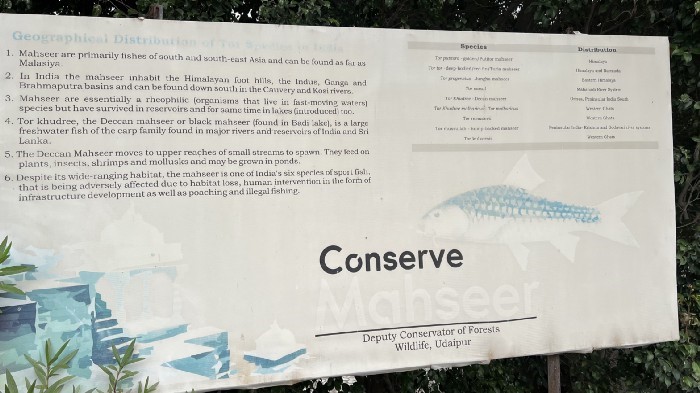

There were scores of fish swimming in the waters below. I learned that these were rare, endangered fish known as Mahseer.

The reservoir has been impounded by a gravity masonry dam. On the other side of the embankment, there were beautiful gorges that were cordoned off by a high railing.

Our next destination was another beautiful lake built in the 17th century called Fatah Sagar which is the second most important source of drinking water for the city of Udaipur. Pointing to a hill nearby with a temple (dedicated to Neemach Mata) on its peak, Jitendra ji recalled that as a boy, an important highlight of his school vacations was that he would first cycle from his home to the lake, run uphill all the way until the temple and then come running down to have a swim in the lake. “Friends and relatives would also join me,” he recollected. I asked if his children today were doing the same. He said the children today were far busier and were not as athletic as yesteryears however his daughter did occasionally cycle all around the lake.

We were soon joined by a young lady engineer Jyoti Tirgar who showed us some more anicuts in a place called Naal in the vicinity of Gogunda. We beheld scenes of amazing beauty and tranquility. It was like a water paradise. I wondered if the stored water would last through the hot summer months that were not far away.

Looking at the anicuts from the civil engineering perspective, one might think these are pretty standard in terms of design. But I noticed that Jitendra ji had made some slight innovations like stairs to help the village women who came to collect water for their households. Piped water had still not come to their homes. I also saw animals drinking water placidly.

Many times I would stop the engineers to ask them who started a certain initiative or brought a change in the working system and I would hear the name of Sriram ji. It was clear that this man had put in an enormous effort. Had the BJP government continued to govern the state, perhaps a lot more would have been achieved in terms of executing the master plan. After talking to people in many places, I got the sense that the program had lost its steam after the government had changed. The continuity was broken.

Our last stop was at a historic Shiva temple in which the Rajtilak (coronation) of the famous and beloved king of Rajasthan, Maharana Pratap had been performed next to a small water tank in the 12th century. Water is a very important part of the coronation rituals of Hindu kings. It was an emotional moment for my husband and me to go inside a temple where the great king himself meditated. However, I was disappointed at the poor maintenance of the temple tank from which priests of the time would have drawn pots of water to perform an Abhisheka for the Maharana. I could have spent hours at the temple, but it was time for a quick lunch so that we could travel back to Jodhpur for the rest of the itinerary.

As we were traveling back, I mulled over the larger impacts of the MJSA program that I had learned about. It was not just another watershed program but one which had been very well led and executed. It had the potential to be a template for every state in India.

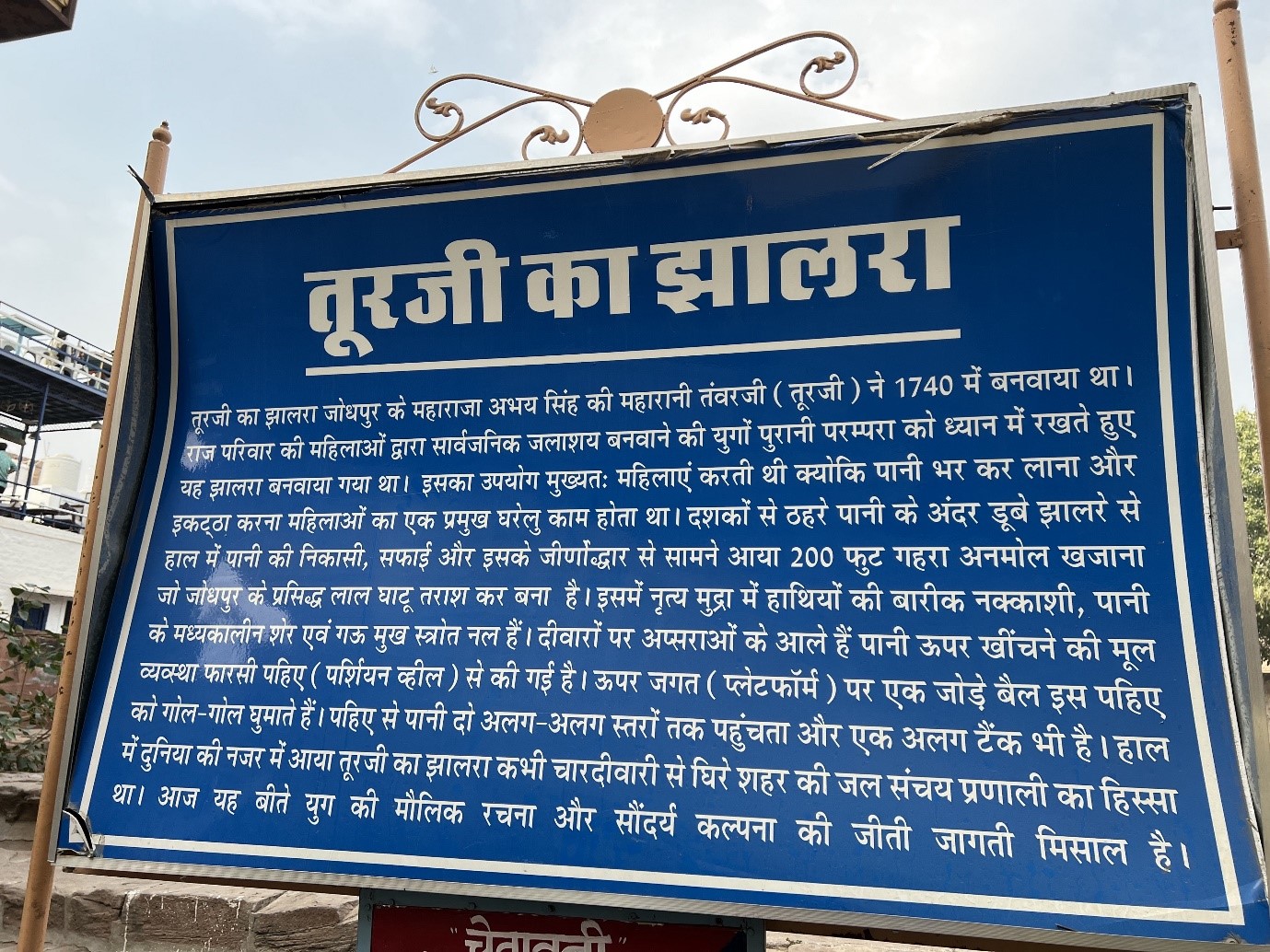

Back in Jodhpur city, I visited a number of historic stepwells that were once used for drinking water. But over the years, with the advent of piped water reaching people’s homes, these places are languishing in extreme neglect and filth. It is astonishing that these wells are not being maintained at least for the sake of attracting tourists.

It is my earnest hope that Rajasthan builds on the achievements of MJSA, expands it to cover every part of the state, and also re-thinks its water and wastewater management in cities. Once tap water and toilets come to their homes, people should not forget their linkages with the rivers, wells and lakes from where they once physically carried freshwater.

In fact, the current water minister of India Shri Gajendra Singh Shekhawat ji who is himself from Jodhpur in Rajasthan had once recalled the words of his grandmother in a speech: “Ever since water began flowing from taps in our homes, we have stopped respecting it,” he had quoted. “As long as we had to all collect water from rivers and wells, we took the utmost care to not overuse or pollute,” he reflected. Indeed, what is the use of harvesting rainwater and raising water tables in villages if it ultimately leads to overuse and pollution from sewage and industrial wastes?

All the images are provided by the author.

Comments