Problem of Freeloaders

- In Society

- 01:47 PM, Apr 23, 2017

- Dharmendra Chauhan

What do you think is the primary reason behind rampant tax evasion, indifference towards public properties and disregard for the rules in our society? Is it because the people are too selfish and care only for themselves, or because they have herd mentality and just follow the crowd? Economists think human as a rational creature who is purely driven by self-interest; in a social situation, he maximizes his own payoff and avoids investing in public goods. On the other hand, sociologists view human as a creature who follows prevailing social norms without regard to self-interest; he internalizes social values to such a degree that there is little conflict between self-interest and social values.

In the real world, however, people exhibit both the qualities: in some circumstances, they follow social norms while in others their self-interest. Unfortunately, neither view explains how individuals adjudicate between the two. How do self-interest and social norms, when in conflicting situation, determine individual's behavior? Here laboratory experiments provide a powerful tool for answering such questions. The public goods game is such a laboratory experiment in economics. This experiment reflects the prevalent reality where everyone contributing to common good is beneficial to all yet costly for an individual. For an example, everyone in a society paying the due taxes is beneficial to all since that money will be spend on security, law & order and public facilities. And yet it is a personal loss to the individual who decides to pay taxes.

The public goods game is played in a group. The game begins with an equal amount in each member's account. The aim of the game—like many other games—is to increase the bank balance. The game has the "public goods" account—the account where each member is asked to contribute. The amount collected in public goods account is increased by a small random factor to reflect the profit gained after an investment. This whole amount is then distributed equally among the members. The format of the game simulates the model of governance. First people are asked pay taxes. Then the tax is invested in the community such that the overall return is more than the investment. Everyone benefits equally, though, the tax contribution was unequal.

The experimental evidence (Ledyard 1995) gave an interesting insight in the group behavior. In the beginning, most of the players acted cooperatively and contributed to the public goods account. After a few rounds of the game, however, the number of contributing players declined. As the game progressed, the number of contributing players kept declining. What was happening? In the group there were some freeloaders who figured out that even if they did not contribute, they would receive equal share of the profit at the end of each round. They were the self-regarding (self-interest first) type individuals who did not contribute to maximize their payoff. Most of the other members contributed to the public goods account initially. However, over the time they noticed that some of the members earn their share without making contribution. It obviously was unfair but they had no way to punish the freeloaders. Having no other option, they gradually stopped contributing. They were strongly-reciprocal type persons. Reciprocal type individuals cooperate initially because they hope others will cooperate too. Nonetheless, when they notice many freeloaders exploiting the system, they do not want to continue cooperating at the cost of their self-interest. Thus, both the free riders and the strong reciprocators contribute little or nothing to the public good towards the end, albeit for different reasons. The self-regarding subjects contribute nothing because this maximizes their economic payoff. The strong reciprocators contribute nothing because they are only willing to cooperate if most of the others also cooperate.

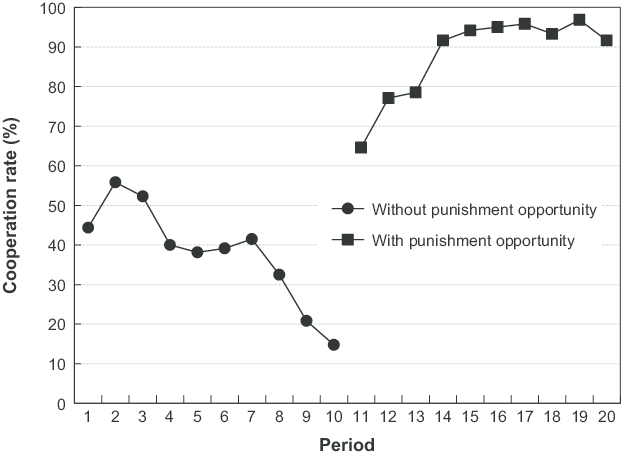

Then, a twist was added to the game. For small fee, members were provided an option to punish the freeloaders. With the availability of the opportunity to punish, the behaviour changed dramatically. Strong reciprocators have a desire to punish free riders because they perceive free riding to be unfair to the rest. When the game rules allowed punishment to freeloaders, the strongly reciprocal subjects were willing to do so even at the cost of paying little fee. In the presence of the punishment, self-regarding subjects found an incentive to contribute in the public goods account. They faced steeper loss in the form of punishment if they did not contribute. Moreover, the reciprocators also contributed happily since they need not fear unfair behavior now. Ultimately, behavior of almost all subjects converged to full cooperation with a level of fairness established in the system.

Cooperation in the absence and the presence of private punishment opportunities

Note that for the self-regarding type members, exercising punishment opportunity does not make sense since that option costs a fee. Paying a fee causes them a net economic loss. Only reciprocators who have internalized the value of fairness in social cooperation are willing to bear the cost of punishing the freeloaders. At the same time, in absence of the opportunity to punish freeloaders, their self-interest will prevent them from cooperating further. Reciprocators think rationally and act in their own self-interest when they cannot change the system, as declared by economists; but also they follow the internalized social norms and bear personal cost to guard a fair system, as claimed by sociologists.

A large body of research has documented important motivational forces behind strong reciprocity. Two of the most prominent forces have been termed “reciprocal fairness” (Rabin 1993, Falk and Fischbacher 2006) and “inequity aversion” (Fehr and Schmidt 1999). A reciprocally fair subject is motivated by the desire to respond to kind acts with kindness and to hostile acts with hostility. An inequity averse subject is motivated by the desire to avoid inequity and to implement equitable outcomes. However, inequity averse and reciprocally fair subjects are no saints who resist unfair outcomes and punish unfair behavior under all circumstances.

Since the early days of human cooperation, keen awareness for fairness has been part of our psyche. Smallest unfair treatment—real or sometime even perceived one—rarely fails to cause discontent. Not only small children but also our primate kin—chimpanzees have been observed to react angrily if treated unfairly compared to peers. In a game called ultimatum game, played by two players as a part of economic experiment, one player is offered an amount to be shared with the other player. The first players is free to divide the money as he deems fit but both can keep money only if the second player accepts the divide proposed by the first. Here, rational second player should be happy with even 90:10 divide since he gets the money "for free". In shared social groups, however, offer of less than 30% is often rejected. The second player prefers both to get nothing instead of the first player getting an "unfair" share.

When we cooperate with our kin—with whom we share our genes—not much is expected in return. On the other hand, our relations with kith are based on loose reciprocity. We cooperate with each other so far the acts are mutually beneficial. Similarly, we expect everyone to contribute their fair share when the effort is for a social cause. Freeloader can be defined as a selfish opportunist who takes advantage of others' generosity without giving anything in return. In society, they take more than their share or contribute less than their due. Theft, cheating and bullying for selfish reasons are three different means to the same end. While a thief requires opportunity and a cheat employs deception, bully has no fear to be caught.

Anthropologist Christopher Boehm studied 50 ancestral societies which were culturally close to the foraging societies evolved in Africa some 45000 years back. He found that "failure to share" was one of the most commonly punished infractions along with murder and theft. Evading hard work and bullying were also high on the list. Punishment, depending on the seriousness of the crime, ranged from public ridicule and ostracism to expulsion or assassination. Such social sanctions had wide support in the group. Blood relations of the culprit did not participate in carrying out the punishment but neither supported him. Strict measures against deviant behavior were crucial for any group's survival in harsh environment. Boehm suggests that in small groups to maintain egalitarian political order it was obligatory to sometime use capital punishment when a menacingly aggressive personality appear in their midst. Hominids that cooperated with one another—and punished those who didn't—must have outfought, outhunted, and outbred everyone else. Punishing antisocial behaviors and rewarding prosocial behaviors also played an important role in forming the moral conscience during social evolution.

However, it is important that the social sanction has backing of the moral majority of the group. It is irrelevant if entire group has reached the consensus or a few people—often deviant's kin—are staying neutral so far the group is behind the decision. Well-unified moral majority is critical for the well-being of a social group since some deviants are too powerful to be taken on by one individual or even few.

Comparison of subsistence-level hunter-gatherer group and modern society is interesting. When living in a smaller group almost everything is open to scrutiny but one can virtually live whole life anonymous in the large society. In modern society we do not share our food literally but pay taxes and serve common interest. Today's scams and frauds—targeting private as well as public properties—are modern equivalent of theft and cheating in tribal societies. Organized criminals are new-age bullies. The contrast, however, is that selfish or deviant behaviors are difficult to get away within a small group but they go uncaught or unpunished in modern society.

In the large modern societies, scheme of members punishing other members for being freeloader is impractical and chaotic. When human lived in small groups, everyone watched everyone else so individuals acted fairly. When larger groups appeared, people had social norms to guide them. In today's heterogeneous society, however, third party punishment—rule of the law is essential. The presence of vigilante groups is a sign of broken law and order system. Tax evasion by large population is a signal from reciprocators that freeloaders are going unpunished. Nonetheless, cracks in the social order do not prove that all people are self-regarding. The way small minority of self-regarding individuals can produce a breakdown of the cooperation, also a small minority of inequality averse people can bring back full cooperation if punishment can be effectively targeted at the free riders.

One of the new challenges faced by successful cooperative system is the second-order social dilemmas problem. A perfectly cooperative society, which needs no punishment, ends up creating a generation of perfect cooperators. Such perfect cooperators are second-order freeloaders because neither they are able to detect freeloaders nor they have desire to punish them. Consequently, their payoffs are higher than those of cooperative punishers. By degenerating the function of punishment, these second-order freeloaders turn the cooperative system fragile.

References:

- Ernst Fehr and Herbert Gintis, "Human Motivation and Social Cooperation" http://www.umass.edu/preferen/gintis/Human%20Nature%20and%20Social%20Cooperation.pdf

- Sebastian Junger, "Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging"

- Ara Norenzayan, "Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict"

- http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378437115007189

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_goods_game

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ultimatum_game

Comments