Phulaguri Dhowa: Another Forgotten Chapter of Indian History (Part-2)

- In History & Culture

- 10:26 AM, Oct 20, 2020

- Ankita Dutta

The Events Leading to the Uprising

On the morning of 17 September 1861, some 1500 farmers of Phulaguri and the neighbouring areas marched to the Sadar Court at Nowgong and waged a mass demonstration against the proposed new taxes. The then Deputy Commissioner of Nowgong Lt. Herbert Sconce who always refused to hear the complaints of the peasants and dealt with them in a provocative and humiliating manner by imposing hefty fines. Some of the peasants reportedly tried to have forced their way into his official chamber where he was transacting his business. But instead of allaying their fears and suspicions, Sconce ordered the trespassers to be detained in the thana for their “riotous and disorderly conduct”.

A local peasant leader named Jati Kalita played an important part in this revolt, eventually becoming one of its most prominent faces. Under his leadership, the rest of the peasants and farmers congregated under the shade of three huge ahat trees on the banks of the river Kolong for seeking retaliation from the government. According to the Datialia Buranji (Buranji meaning Assamese chronicles), the Panchoraja (five kings, viz. Sararaja, Kahigharia, Topakuchia, Baropujia, and Mikir Raja) and Satoraja (seven kings, whose areas of jurisdiction were Tetelia, Mayong, Baghara, Ghagua, Sukhnagog, Tarani, Kalbari, and Damal) also joined in the revolt against the government.

The mindless atrocities committed by the Chaudhuries and Tehsildars upon the hapless peasants were also, in part, responsible for the Phulaguri outbreak of 1861. The announcement by the Tehsildars that the properties of the defaulter peasants would be seized in the eventuality of non-payment of revenue, created a situation of scare and anguish in the minds of the peasants against the government. Tenants suffered a lot under the ruthless exactions of rich landowners, who enjoyed full protection of the colonial state machinery. In the meantime, the government had strengthened its police force to create a sense of fear among the restless peasants.

Almost a month had passed by since the protest demonstration of 17th September. But the magistrate remained unrelenting on his stand and showed no signs of withdrawing the new taxation structure. Accordingly, a Raijmel was scheduled to be held from October 15, 1861 for five days at a stretch to discuss about the matter in detail and also chalk out a future course of action on the non-payment of taxes. This was done to enable the participation of peasants and farmers from some of the distant and remotest villages of Nowgong and the surrounding regions. Peasants of Raha, Jagi, Kahighar mouza, Barapujia, Chapari, Kampur, Jamunamukh, etc. attended the meetings on different days as per their convenience. The leaders of the meeting had decided upon including both Sunday and Wednesday within their five days’ deliberations because both these days were the days of weekly markets for the people of Raha and Phulaguri. Hence, huge mass gatherings were expected.

It was around this same time that the government, on the advice of one British official James Wilson, had introduced another new form of tax called the license tax, which forced people to pay taxes on their residences too. This further sharpened the belief of the villagers, particularly of the majority Tiwa tribals of Phulaguri, about the forthcoming taxes which were to be soon imposed by the British government after conducting the required feasibility studies. Upon the receipt of intelligence inputs that a large number of peasants were preparing to meet at Phulaguri on October 15, Sconce immediately sent a police team led by a daroga to the spot ordering them to disperse the “unlawful” assembly and arrest the ring leaders.

When on the 15th, the police party arrived at the place of meeting and ordered the leaders of the assembly to disperse, the latter defied the orders, retorting that they had organised the meeting to discuss matters of their common interest. Pitted against a crowd of more than 1,000 people, some armed with clubs (lathis) and bamboo sticks, the police retired and reported to the Deputy Commissioner about the proceedings of the Raijmel. Another police officer who was dispatched on the following day also failed to disperse the assembly of the peaceful protesters. It was on the 17th of October, 1861 that the daroga arrested some of the leaders of the Raijmel, but the emotionally-charged mob successfully overpowered him and helped in releasing their arrested leaders. The Deputy Commissioner was told that unless stringent measures were taken to drive away the crowd from Phulaguri, it was impossible to do anything concrete at the risk of one’s life.

The Uprising

Considering the seriousness of the situation, on October 18, 1861 Lt. Singer, the then Assistant Commissioner of Police of Nowgong district, directed by Herbert Sconce himself, reached the spot on horseback accompanied by a large number of troops. Singer ordered the police forces to forcibly disarm the rebels, numbering over three thousand, while he foolishly attempted to seize the sticks and lathis in the possession of the crowd. A scuffle ensued soon after and the cries of “dhor dhor, maar maar” (seize, seize, kill, kill) filled the air. In a fit of rage, the protesters stabbed Lt. Singer to death besides killing Golap Singh, the daroga in-charge of Raha police station. Their bodies were later dumped into the nearby Kolong river. Several other police officials who were injured in the course of the revolt died soon after. The rest fled the spot in panic. But this particular incident suddenly triggered a brutal and merciless retaliation from the colonial state and it finally took over control.

On hearing about the fate of Lt. Singer and the police officials, Herbert Sconce became insecure. It was rumoured that the furious peasants would soon arrive from Phulaguri to the Nowgong district headquarters, burn down the building and loot the treasury. To take stock of the situation, he immediately dispatched a party of police officials under Haladhar Barua, the then daroga of Nowgong, to Phulaguri and sent a communiqué to the Deputy Commissioner of Darrang district, calling for urgent reinforcements. The police party arrived at Phulaguri in the early hours of October 19, 1861. A skirmish followed in which the daos, spears, bows and sticks of the peasants could but offer only feeble resistance to the indiscriminate police firing. Several of them died on the spot and many were left wounded. Even pregnant women and children were not spared from such inhuman atrocities.

The flames of smoke (Dhowa) which arose from the surroundings as a result of the firing came to be associated with the popular imagery of this event in the folk memory of the people of Assam; hence, the name Phulaguri Dhowa.

In the evening of the same day, Henry Hopkinson, the Commissioner of Assam, arrived at Tezpur while on his way to Dibrugarh in Upper Assam. He reached Nowgong on the 23rd of October, 1861 along with a team of the Assam Light Infantry, and made timely arrangements for the dispatch of troops from Tezpur to Phulaguri to bring the situation under control. He made personal visits to Phulaguri, Nellie, Kachuhat, and Raha and ordered the arrest of 41 persons, including the sons of the “old Lalung Rajas”, alleged to have been implicated in the murder of Lt. Singer. As per a government estimate, a total of 141 persons, including eight Tiwa leaders, were arrested and kept in the make-shift jails of Raha and Nowgong under the most inhumane conditions. They were later tried at Nowgong and Calcutta. Many of them were awarded life imprisonment and a few prominent leaders such as Lakhan Deka, Banamali Kaibartta, Bahu Kaibartta, Songbor Lalung, Hebera Lalung, and Ronbor Deka were sentenced to death on the charge of killing a ‘White Officer’.

An estimated total of 54 farmers lost their lives at Phulaguri; while some were gunned down, some were burnt alive. Many were grievously injured, a few others were hanged while a few of them were deported to the Andaman Islands also called Koliapani in Assamese, and 60 farmers were imprisoned for 1-10 years. The dead bodies of some of the rebel peasants were secretly cremated by their near and dear ones on the banks of a beel near Phulaguri, for they were sacred that if, in any case, the government identified the dead-bodies of the deceased, it would spell doom for them. The casualties were huge, but the colonial machinery concealed the real numbers from the public. Although a judicial enquiry was held after the incident which found Sconce to be at fault in not granting an audience to the people and sending an inexperienced officer to deal with a defiant crowd, he was let off with only a temporary suspension from his post.

It needs to be mentioned here that the farmers and peasants of Bengal had revolted in the previous year,1860. But their ire was against the exploitative indigo planters and not specifically against the British administration as such. In this sense, the historic Phulaguri Dhowa can be said to be the first organised peasant movement of colonial India that left the British administration shaken for the first time in the Northeast. It was also the first-ever non-cooperation movement of the Indian freedom struggle and the maiden agrarian revolt of Assam, which challenged the defensive capability of the British administration in the Brahmaputra Valley.

The resentment of the poor peasants and farmers of Phulaguri who stood in open defiance of their rulers, had eventually led to the stoppage of the payment of taxes to the British administration. Their spirit of sacrifice and remarkable organisational ability was something which the British too, could no longer ignore. Within a period of a few years, it realised the necessity of introducing certain changes and revisions in the taxation structure, including a reduction in the land revenue rates. Although the rebellion was ruthlessly contained, but it stood out as a unique form of militant resistance that had not happened anywhere in India before Phulaguri. The Tiwas and Kacharis of Nowgong being the hardest hit by the prohibitory measures of the government stood at the vanguard of the movement.

Also known as Lalungs in the Assamese Buranjis, the Tiwas are a major ethnic community of Assam, chiefly concentrated in the districts of Nagaon, Morigaon, N.C. Hills & Karbi Anglong, Jorhat, Sibsagar, Dhemaji, and Kamrup (Rural), besides the Khasi and the Jayantia districts of neighbouring Meghalaya. The Tiwas have been enlisted as a scheduled tribe (Plains) within the state of Assam, but a section of them resides in the hill areas too. They displayed exemplary heroism in their resistance against the British at different stages of the Indian freedom struggle. The Tiwas of Raha, Bebejia, Barapujia, Kampur, Hojai, and Jamunamukh in Nagaon had participated in large numbers during the Quit India Movement of 1942.

The Kacharis belong to the Dimasa-Bodo-Kachari group and are believed to be the descendants of Ghatotkacha, the son of Bhima. They ruled from their capital at Hidimbapur, i.e. present-day Dimapur. In Assam, the Kacharis are primarily concentrated in the districts of Dibrugarh, Tinsukia, Dhemaji, Sibsagar, Lakhimpur, Jorhat, and Golaghat.

An Analysis

Unfortunately, the NCERT history textbooks on ‘Modern India’ have completely brushed under the carpet these revolutionary episodes of Indian history from Northeast India. The Northeast has contributed in its own unique way to help India attain freedom from the clutches of the British. But an elite club of “eminent historians” always kept the country divided by either hiding or manipulating much of the real history and culture of the Northeast. This same group of “intellectuals” use the banner of ‘racial discrimination’ to stoke the flames of hatred and anger among the people of the Northeast against mainland India. Evoking such passions of the people especially in a region as sensitive as the Northeast is quite easy. But it is the academic dishonesty of the Left-dominated ecosystem that has arrogantly denied acknowledging the true history and peculiar diversity of the region the way it is.

Real integration of the Northeast with the rest of the country cannot be achieved unless its history remains neglected and side-lined from the academic discourse.

Even at the time of the outbreak, various academic writings by the so-called “intellectuals” of Assam completely ignored the chain of events that finally led to the uprising. For instance, Arunodoi – the first Assamese newspaper that was published at the behest of the Christian missionaries – caricatured and made fun of the peasants involved in the struggle. Since the Christian missionaries were hand-in-gloves with the authorities, they supported the revenue hike1. The Arunodoi even went on to mention that the rates of revenue in Assam were so low and nominal that such negligible rates could not ever be imagined in the other provinces of India! During the annual Durga Puja festivities that were held at Phulaguri in 1861, the Christian missionaries took full advantage of the wretched condition of the peasantry by distributing religious pamphlets which preached the Gospel of Jesus that claimed to save people from their poverty and other natural calamities. The peasants could not find it convincing enough and soon realised that in the garb of “charity”, the missionaries were working as agents of the colonial authorities.

There is a huge sub-text to the entire narrative which has, for so long, been ignored not only by writers and scholars from all spectrums, but also by those farmers’ and peasants’ organisations currently active in the political scenario of Assam. Phulaguri Dhuwa stands out as a remarkable, yet an unacknowledged historical event in its own right. It was not merely just another ordinary battle between an agitating crowd and an armed force of the British Government for the prohibition imposed upon opium cultivation, but also against a slew of taxes. It was the earliest of the popular peasant movements in Assam against the exploitative policies of the colonial government. Champaran, Kheda, etc. definitely deserve their own revered place in the annals of history writing. But it’s high time that an honest academic discussion of farmers’ and peasants’ movements in colonial India give equal credit to episodes such as Phulaguri too.

Phulaguri is the most significant events of India’s struggle for Independence that sowed the seeds of nationalism quite early on. It underlines the indispensable role played by farmers and peasants in the development of the nation and its economy. It should not be glossed over as a mere riot of a local nature without any major consequence whatsoever; nor should it be confined to the realm of a ‘tribal movement’ alone, as has been generally done by historians. The educated Assamese middle-class consisting of small land owners, government servants, mouzadars, traders and merchants who were no less affected by the recent taxes on income, property and dealings, not only actively cooperated but also extended their whole-hearted support to the peasants. Interestingly, even those “scholars” and “academics” who share an unending romance with ‘subaltern history’, have left this glorious chapter of peasant uprising in a backward and isolated village of a state in Northeast India completely omitted from their academic writings.

Whatever staggered writings exist on the subject till date, they have either been heavily lopsided with ideological underpinnings and/or informed by an agenda that has, in some way or the other, tried to give credence to the Communist cause in the name of ‘peasant revolt’!

Two notable plays have been written on the epochal event at Phulaguri and its consequences thereafter, by renowned dramatist Saradakanta Bordoloi and another by Kamal Singha Deka, a resident of Phulaguri. By and large, this historic episode seems to have been almost erased from the public memory. Situated at a distance of nearly 105 km east of Guwahati city, Phulaguri continues to remain backward even today. In a welcome step, the Bharatiya Kisan Sangh, an RSS-affiliated famers’ organisation, had organised the ‘Phulaguri Dhawa Smriti Divas’ on October 20, 2019 at Phulaguri, Nagaon. On the occasion, Assam CM Sarbananda Sonowal had highlighted the visionary policies and programs of the current dispensation at the Centre led by Narendra Modi which is gradually paving the way for transforming the Indian agriculture sector.

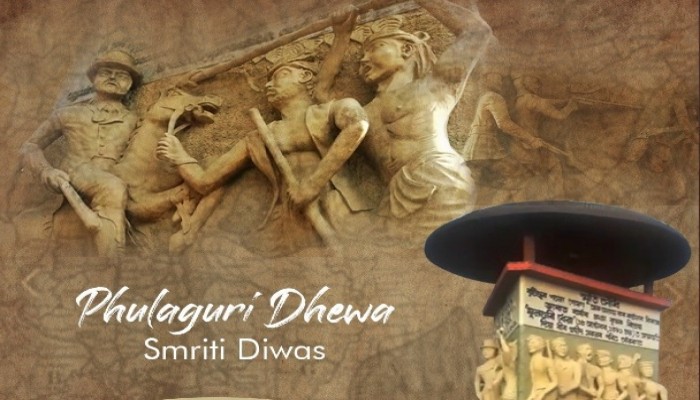

Unfortunately, in Assam, very few today remember the sacrifice of the Phulaguri martyrs. On a small note, the present generations of the families of these martyrs gather every year any day from October 15-20 on the banks of the Kolong river and organise an hour-long program and a public meeting in front of the martyrs’ monuments, which depict the peasants fighting the British soldiers through a beautiful work of art. Except these memorials that were put up in the year 2004 during the NDA-regime of former PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the people of Phulaguri have not received anything significant from the successive governments at both the Centre and the state as a mark of remembrance of this heroic incident.

Phulaguri does not merely represent just another sporadic peasant outburst; this momentous day of an unprecedented wave of public discontent became a symbol of challenge to the mighty British Raj in the then undivided Nowgong province. It also displayed the uncompromising attitude of the Assamese people against the various anti-people policies adopted by the British that had led to the destruction of their village-based, traditional ways of life and livelihood.

Phulaguri is indeed one of the most tragic yet a heroic and inspiring saga in the history of the Indian freedom struggle. To immortalise the forgotten legacy of Phulaguri in the pages of history, it needs to be promoted as a major tourist destination with all the necessary infrastructural facilities to showcase the contributions made by India’s Northeast to the freedom struggle. In 2011, the Nagaon district administration had formulated a plan to unearth the history of the Phulaguri Dhowa, almost 150 years after the occurrence of the event. It is because many aspects of the Phulaguri Dhowa still remain in the dark or unknown to the masses at large. Even a 25-member-fact-finding-committee, comprising of intellectuals, historians and college teachers of Nagaon district, was supposed to be constituted at the behest of the district administration to prepare a detailed history on the movement, including its “hidden causes” and the sentiments of the “agitated” farmers. However, not much seems to have been executed on the ground till date and the setting up of the committee too, has remained a pipe dream!

References:

- https://indiafoundation.in/articles-and-commentaries/periphery-in-indias-independence-movement-a-re-look-from-northeast-india/

- Amalendu Guha. Planter Raj to Swaraj: Freedom Struggle and Electoral Politics in Assam, 1826-1947. Tulika Books. New Delhi, 2006.

- S.D. Goswami. Raij versus the Raj: The Nowgong Outbreak of 1861 in a Historical Perspective in J.B. Bhattacharjee (ed.) Studies in the Economic History of NE India. NEHU Publications, Shillong, 1986, pp. 121-128.

- Shruti Dev Goswami. The Phulaguri Uprising: An Appraisal. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Vol.40 (1979), pp. 557-565. Accessed from https://www.jstor.org/stable/44141995?seq=1

- https://www.telegraphindia.com/north-east/panel-to-unearth-nagaon-s-first-peasant-revolt/cid/339650

- https://tiwatribe.blogspot.com/2015/06/a-study-on-autonomy-movement-of-tiwa.html?m=1

- https://www.telegraphindia.com/north-east/monument-to-momentous-revolt-phulaguri-peasant-uprising-of-1861-to-come-alive-in-concrete-memorial/cid/711219

Acknowledgements: A special note of thanks to my dear friend, sister and colleague Jayshree for enlightening me on several aspects of the issue.

Image Credits: 'All About Assam' https://allaboutassam.in/2019/07/kanaklata-barua/

Comments