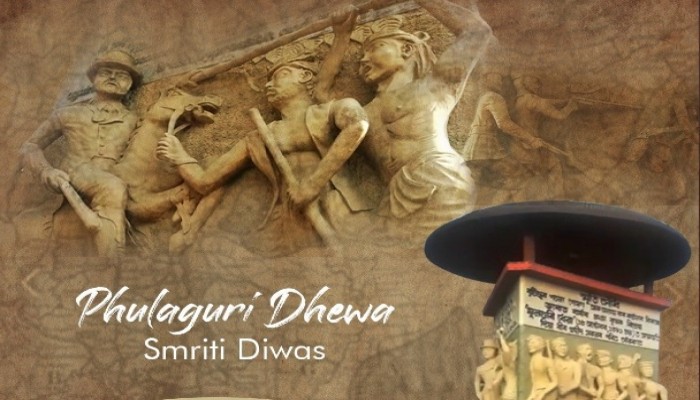

Phulaguri Dhowa: Another Forgotten Chapter of Indian History (Part-1)

- In History & Culture

- 10:34 AM, Oct 19, 2020

- Ankita Dutta

“History cannot give us a program for the future, but it can give us a fuller understanding of ourselves, and of our common humanity, so that we can better face the future” – Robert Penn Warren

Not many might be aware of the fact that much before M.K. Gandhi had mobilised the masses at Champaran and Kheda in the 19th century, the peasants of a remote and nondescript revenue village called Phulaguri in the western part of central Assam’s Nagaon district, dealt the first-ever blow to the British in the Northeast on October 18-19, 1861. It was the culmination of several deep-rooted grievances of the people against the oppressive land revenue laws and policies of the British. For those who might not be familiar with basic Assamese nomenclature, the origins of the word ‘Phulaguri’ may be traced to Phul which means flower in Assamese, and the suffix Guri implies the surrounding area/locality. The word ‘Phulaguri’ therefore denotes a place where flowers are to be found in abundance. Located at a distance of about 15-17 km away from present-day Nagaon town, the NH-37 passes through the heart of Phulaguri. The annual flood waters of the rivers Kolong, Kopili, and Haria inundate the plains of Phulaguri every monsoon.

There is also a popular belief associated with the name ‘Phulaguri’. It is said that the people of Phulaguri had invited the Koch king Naranarayana and his brother Cilarai (both were the supreme patrons of Srimanta Sankardeva’s teachings within the broader umbrella of Sanatan Dharma) to their place just after they handed over a crushing defeat to the Jayantia king Bijoymanik. They organised a grand durbar in honour of the two. The durbar was decorated with wild flowers of different colours and variety. Cilarai was overwhelmed with joy upon seeing such a wonderful bounty of fresh, colourful flowers, and thus named the place ‘Phulaguri’. Although it is quite difficult to trace the historical origins of the name of this place, but it is almost accepted with certainty that ‘Phulaguri’ is named after phul or flower. Some local people of the village, after having cleared the wild flowers and jungles, established a haat (market) on the banks of the Kolong river, which is still known as Phulagurihaat (Phulaguri market).

The Ban on Opium – Beginning of an Impending Rebellion

Popularly known as ‘Phulaguri Dhowa’, the revolt was the outcome of a ban imposed on poppy cultivation in the area from May 1, 1860 and a proposed taxation on tamul-paan (areca nut and betel leaf), which are the two most important and essential items in any religious and traditional rituals of the Assamese people. There are several references to the chewing of betel-nut and its cultural and religious importance in the Kalika Purana and the Smriti Sastra. As written by Indreswar Goswami in his article titled Asamor Pratham Krishak Bidroh, some British writers have also referred to the Phulaguri uprising as the ‘Opium-eaters’ Revolt’ or Kania’r Bidroh – Kania comes from the word Kaani (the Assamese word for opium), implying the Assamese opium eater/smoker and Bidroh means revolt. Since opium was one of the most important sources of income of the peasants and farmers of Phulaguri, such a measure of the British government threatened to shatter the entire economy of the region.

Colonel Francis Jenkins, agent to the Governor-General of the North-East Frontiers, was the main mastermind behind implementing both the ban on poppy cultivation and the introduction of sufficient quantity of government opium for sale in the province. In reply to an official dispatch of the Bengal Government dated 20th January 1860, Jenkins, while expressing his opinion in favour of effecting the immediate ban on poppy cultivation with effect from May 1, 1860 said – “There will be no difficulty in supplying any part of Assam with the government drug through ordinary vendors and in fact, the necessary measures to this effect have already been established.”

Here, it is important to mention that the British Government did not ban the cultivation of opium out of concern for the health and well-being of the people of the state. For some time now, the government had been suffering losses in its opium trade, an item which it used to buy from the northern plains of India. Since Assam was identified to be a huge producer and market for opium, any production of opium here would have further reduced its cost resulting in huge losses to the British coffers. Hence, the government began the sale of opium that was brought from north India at an abnormally high price in Assam, and imposed the subsequent ban on poppy cultivation in the state.

Opium had a sacred and symbolic meaning in the day-to-day lives of the people of Assam, and the ban imposed on it hurt their religious and cultural sensibilities. Opium used to be a very important part of the people’s traditional and religious belief systems, besides its applicability in curing health complications such as dysentery, malaria, joint pain, etc. People who were regular consumers of the drug believed that in Satya Yug, since poppy trees grew in abundance in the Parijat garden of Lord Indra, the latter gave the juice, i.e. opium, obtained from the bark of these trees, as a priceless gift to the people on the earth. Moreover, the British officials had also started levying stamp duty, excise duty, etc. and exorbitant rates of taxation on several basic items of regular use like bamboo, water (jalkar), firewood, khusary or grazing tax, tax on cutting grass and trees in jungles or gorkhati, tax on fishing in the rivers and beels, washing of gold, fodder for animals, etc.

Tea Plantations & Colonisation of Agriculture in Assam

All these factors, along with an ever-increasing inflow of immigrants who were brought in by the British to work in the newly-established tea plantations of Assam, practically impoverished the peasantry beyond description. The common Assamese labouring class had refused to become the servants of the Boga Saahab (‘White’ officials) and work in the tea estates for minimal wages. They were so firm in their belief that even after parting with their ancestral lands upon the orders of the British in order to make way for tea gardens, they never agreed to expend their labour on these large British-owned estates. As a result, cheap labour was brought in from present-day Jharkhand and the Chhotanagpur plateau region to work in the tea estates of Assam. A fake narrative of Kaani-khua Axomia (‘Opium-eating Lazy Assamese’) was subsequently created by the British in order to suit their political and economic interests, much to the detriment of the fighting-spirit of the Assamese community.

Very soon, it became clear that the British administration was hell-bent on driving out the indigenous peasants and cultivators from their traditional homeland for their refusal to serve the British, and introduce tea plantations in the area. The prospect of tea cultivation in Assam inspired Jenkins to suggest in 1833 a colonisation scheme as an experimental measure for settling the rich capitalists and businessmen from England in the both the wastelands and grazing fields of Assam. Against the nominal rates of taxation or the absence of it on plantation lands, revenue on other cultivable lands increased at an enormous rate. In Central and Lower Assam, a tax called gaadhan amounting to Rs. 2 per head was also imposed for which a farmer was entitled to three puras of arable land. In any agrarian economy even today, land is not merely a source of cultivation or for building houses; it is a symbol of a person’s social status. Imposition of any unfair rates of taxes on land was thus taken as a challenge by the peasants to their rights and social status.

Increasing Revenue & Taxation Rates – An Unwelcome Change

Som tree plantations in forests in which the Muga-silk yielding silkworms were reared, also came under the taxation system of the British. It was compounded by the complete lackadaisical attitude of the government towards the development of the agriculture sector through the construction of embankments, bunds and other means of communication, etc. which adversely impacted the rural economy. In 1822, locust-attacks had led to an almost wholesale destruction of the crop harvests in Phulaguri, resulting in an acute food scarcity. A second blight occurred in 1840 and another in 1858. This was aggravated by the appearance of several other unknown pests and insects which ate away all the crops. A high rate of mortality of cattle during this period caused a further deterioration of the economic and agricultural conditions of the peasantry in the region.

Unfortunately, the measures undertaken by the government to stem the tide of destruction were far from satisfactory. There was neither a system of crop insurance in place nor cheap facilities for credit which could provide relief and compensation to the poor peasants from the damage caused by floods, insects, droughts, etc. Large-scale destruction of forest wealth for timber and railway bunkers added to the woes of the villagers. A rumour soon spread like wildfire in Nowgong district that the government was contemplating to impose taxes on people’s houses and baris (homestead gardens) too. This was to be paid alongside the land revenue that the peasants were already being made to pay under the Ryotwari system. In fact, a major portion of their income was already being spent on paying the government dues. Although the official circles dismissed these rumours as “unfounded”, but it was enough to annoy the local people of the area who mostly belonged to the Tiwa tribe, and a small section also included people from the Kachari tribe. They were aided by the Kaibartta community of the area who dealt with the business of procuring and selling of fish.

From opium to bamboo and water to the woods in the jungle, not a single item of regular use was spared from the oppressive taxation measures of the colonial state. Official records show that after the First War of Indian Independence in 1857, the British government had increased the revenue demand by 3-4 times of the original amount. Between 1826-1853, the land revenue rates were enhanced arbitrarily on several occasions. The harmful effects of the excessive revenue demand were further complicated by the rigid manner and anomalous nature of its collection. Also, the systems of classification of different categories of land were neither scientific nor based upon the actual productivity of the soil. The cadastral surveys that were conducted from time to time were also found to be defective. Repeated pleas of the peasants through numerous petitions to the government fell on deaf ears.

During the period of rule of the erstwhile Ahom dynasty in Assam, Assamese aristocrats who held posts like Phukan, Barua, Rajkhowa, etc. were vested with the responsibility of tax collection. But, with the coming into power of the British, these responsibilities were transferred to outsiders like Bengalis from Srihatta in Bengal or Marwaris and Jains from northern and western India. The native Assamese people were not accustomed to such changes. They became restless. The Ahoms had respected the right of the farmer over his land and property as supreme and never violated with it. But, under the rule of an alien political and cultural force, the farming community now felt abandoned in their own native lands.

The weakening of the authority of the Ahom dynasty was compounded by a serious economic crisis in both the plains and hills of Assam. When the British finally took over the revenue administration after the Treaty of Yandaboo (1826), the sector which was most affected as a result of the economically draining policies of the colonial state was agriculture. It was the chief source of income for most of the common people of Assam and the burden of increased taxation largely fell on the peasantry. The principal motive behind the numerous land revenue settlements introduced by the British was the maximisation of income from the land. The peasants were made to surrender to the state a large proportion of their agricultural output, resulting in a severe strain on the peasant economy of Assam. In due course of time, it not only resulted in a thorough transformation of the entire agricultural scenario of the region but also reduced many a farmer to mere cultivators, who vented out their anger and frustration through resistance movements such as the one at Phulaguri.

Phulaguri inaugurated a new era of peasant awakening in the country and was followed by a series of peasant revolts in Rangia, Lachima, and Patharughat during the period 1893-94.

Some immediate causes that had led to the outbreak of the Phulaguri Dhowa in 1861 were the imposition of the cultivation of Akbari opium and increased rent rates. Akbari opium was sold on a monopoly basis by the government and was more expensive than the one which had been cultivated in the area since a long time. Nowgong had the maximum acre of land area under poppy cultivation. Since it was the largest opium-producing district in Assam, it inevitably became the most widely affected as a result of these high-handed policies of the British. The agricultural and commercial importance of Nowgong during the colonial period was also enhanced by the fact that it had good water communication routes to Guwahati throughout the year. As written by Purnakanta Nath, the colonial government realised Rs. 1,55,651 in 1852-53 from land revenue and other taxes from Nowgong district alone. “In all possibilities, the government had resorted to harsh methods in realising such a high amount of revenue, which further fuelled the already pent-up anger and grievances of the peasants against the system” (Nath, 2004).

Village Assemblies (Raijmels) – A New Mode of Protest

The peasants became scared at the prospect of cultivation of Akbari opium for which they would have to pay dearly, eventually compelling them to work in the British-owned tea gardens of Assam as daily-wage workers. At that time, village assemblies called Raijmel were popular and prominent institutions in Assam, which provided the people with a platform to express their opinions on important socio-economic and political matters affecting their day-to-day lives. They would discuss matters of common interest, particularly social and economic issues such as the imposition of new taxes or the enhancement of land revenue, etc. and a final decision was taken keeping in mind the overall well-being of the people. The Raijmels were mostly popular in the districts of Kamrup, Darrang, and Nowgong. With the gradual passage of time, these Raijmels had evolved into real assemblies of the people, which provided representation to not only members of a particular village where the Raijmel took place, but also people from other villages too.

The Raijmels were generally held under the leadership of prominent religious dignitaries such as the heads of Sattras and Namghars (Hindu religious institutions of Assam) called Goxains, respectable landholders, village headmen or other influential villagers. They grew in strength with each passing day, raising issues which questioned the invincibility and the legitimacy of the colonial state to rule over its subjects. In the Phulaguri Dhowa too, these Raijmels played a crucial role in mobilising the common masses against a genuine cause, thereby imbibing in them the spirit to fight back with pride and without bowing their heads in front of the foreigner. The British Government became increasingly alarmed at the growing influence and popularity of the Raijmel in different places of Assam and considered it as a source of danger to its power and authority. In many instances, the Raijmel was also banned.

According to a few contemporary British administrators, events such as Phulaguri were the evil result of the sinister designs of these Raijmels!

The Tiwas of Phulaguri had started utilising the institution of the Raijmel as another mode of protest against the undemocratic imposition of the new taxes. In other words, Phulaguri Dhowa was the first instance of determined resistance by poor peasants through the institution of the Raijmel. Even today, the Raijmels are popular institutions in the rural areas of Assam for social and religious purposes and as well as for the vocalising common economic and political grievances. Although such novel measures of protest could not put an end to the enhancement of revenue on opium, or the supply of government opium, but it did much damage in challenging the authority of the British Government. A simmering discontent gave way to a full-blown rebellion. As rightly remarked by Amalendu Guha, “encouraged and influenced by the Jayantia revolt, the peasants of Nowgong also started agitation against the authority” (Guha, 2006).

References:

- Dr. Himangsu Sarmah. (2017). Toponymy of Nagaon District. Partridge Publishing, India.

- Indreswar Goswami. Asamor Pratham Krishak Bidroha: Phulaguri Dhewa in Jatin Medhi (ed.) Phulaguri Dhewar Rengoni. Published by the 143rd Reception Committee, Anniversary of Phulaguri Dhewa, Phulaguri, Nagaon, 2004, pp. 10-13.

- K.N. Dutt. The Post-Mutiny Raij-Mels Of Assam – An Aspect of The Freedom Movement. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Vol.18 (1955), pp. 216-232. Accessed from https://www.jstor.org/stable/44137389?seq=1 on 16.10.2020

- Purnakanta Nath. Phulaguri Dhewa in Jatin Medhi (ed.) Phulaguri Dhewar Rengoni. Published by the 143rd Reception Committee, Anniversary of Phulaguri Dhewa, Phulaguri, Nagaon, 2004, pp. 14-15.

- https://indiafoundation.in/articles-and-commentaries/periphery-in-indias-independence-movement-a-re-look-from-northeast-india/

(To be continued….)

Image Credits: 'All About Assam' https://allaboutassam.in/2019/07/kanaklata-barua/

Comments