Mitra Mela in Krantidoot Series

- In Book Reviews

- 12:05 PM, Aug 14, 2022

- Saket Suryesh

An intellectual says a simple thing in the hard way. An artist says a hard thing in a simple way. - Charles Bukowski

I met Manish Shrivastava a few years back. What struck me most was the utterly endearing sincerity in his being. That sincerity and simplicity with which he would offer me Rudraksh maala comes out in his writing. When we met first in a Noida Coffee Shop, I was a little circumspect. Such genuineness in today’s world is so rare that one tends to believe it to be some sort of an act being put up for some purpose. But as we sat talking with hope and sadness about the way history of India in general, and our freedom struggle, in particular, has been written, I could see that this honesty was not an act. I had around that time translated the Autobiography of Ram Prasad Bismil- The Revolutionary and was still overwhelmed by the greatness of the person of Bismil. We sat and spoke among us for hours on how a skewed history of India’s great freedom struggle has been held hostage to a particular narrative, written with an aim to further the political objectives of the present and what could be done to rectify it. We both agreed that it is too serious a thing to be left to the Government alone.

The story of India’s freedom struggle as told till now moves in spurts and lacks continuity. If one were to read it from the popular sources, one would believe that post the first war of Independence, which has been projected by the British as a murderous mutiny by a murderous mob, there was a brief lull, during which AO Hume, erstwhile British bureaucrat formed Congress and then Gandhi arrived from South Africa and metamorphosed a sleepy movement of elites and brought it to the masses. While it is true that Congress for almost half a decade was a loyalist British-sponsored convention of Indian elites, which Gandhi did manage to broad base as a popular movement, this presumption that until then there was no activity towards freedom is hugely misplaced.

From Sanyasi movement to the armed resistance in Maharashtra to the revolutionary movement in Bengal and Aryasamaj in Western India to the revolutionaries of Central provinces under the Hindustan Republican Army- the zeal to free the motherland continued unabated. India was not a Cinderella in pink-frock waiting for her knight in shining armor to arrive from South Africa to liberate it. The movement however was not an elite movement. It was made of men like Tilak, Savarkar, Shyamji Verma, Bismil, Azad, Ashfaq and Bhagat Singh.

When one reads about these great leaders and revolutionaries, one thing one is absolutely taken aback by their almost universally modest upbringing of theirs, their unflinching love for the motherland, and above all, their supremely splendid intellectual prowess. This particular aspect of their personalities makes me wonder if the reason that they were hidden from us was merely political or was it because there was some sense of intellectual inadequacy of our later leaders who were mostly academically poor and obtained education merely owing to their affluent backgrounds? In a zeal to build an aristocratic history of India, we took away from our present the inspiring heroes from the past, who rose through deprivation and poverty and became academics and intellectuals.

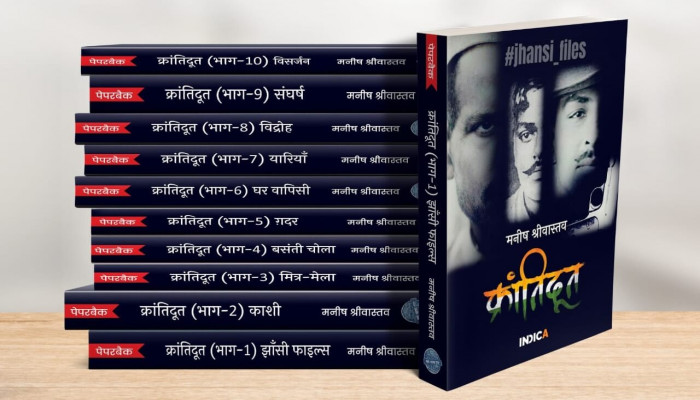

This book ‘MitraMela’- a gathering of friends- taken from the first revolutionary group legendary freedom fighter, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, formed, is third in the series of Ten books the author has planned to write, in this praiseworthy attempt to resurrect those lost heroes. One big casualty of caricaturization of history is that while they make the heroes too big in stature, they reduce everyone else so small in size that they are like miniature toys in the background not worthy of any attention. While this is unjust to the great heroes, it also is unjust to those who we are trying to make appear as giants of history.

Apart from the commendable motive of Manish behind writing this series, what is exceptionally notable here is that his writing allows all those personalities to come out of hiding and breathe in the fresh, free air of India for the first time. In his earlier book in the series, on Chandra Shekhar Azad, we have Masterji, living and breathing as a much respected revolutionary leader.

In this book, while it tends to explore the history of Savarkar or rather the making of Veer Savarkar, it narrates the story of Bhai Parmanand and Shyamji Verma too with great affection. It fills human colours into the names of Bhai Parmanand and Shyamji Verma, both great academics, Professor Bhai Parmanand who headed the History department at Lahore University and Professor Shyamji Verma who came from a poor family and based on his academic brilliance became a professor at Oxford.

Much like the previous books in this series, the narration is in the story-telling pattern. As we had in the second book of the Krantidoot series, Kashi, where Azad as a young recruit in the Hindustan Republican Arm, as an off-shoot of Anushilan Samiti is told the history of a revolutionary movement and key characters are introduced, here the backdrop is of National college also known as Tilak School of Politics in Lahore (Tilak was from Pune and this College is in Lahore, then Western India, now Pakistan, and we are told that before Gandhi and Congress, there was no national movement for freedom which ran across the regions) where Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and other students are being introduced to Savarkar, the revolutionarily movement in England, by their teacher, Bhai Parmanand, himself a noted leader of Gadar movement.

Somewhere, the reader is transformed into one of those students of National College, Lahore and almost imagines himself or herself sitting on the classroom benches, elbows on the desk and face held between the palms, charmed with the story of Savarkar who could with the sheer power of his words transform the disdainfully passive into a daring patriot. The story touches upon the hard research that went into the first proper record of India’s first war of Independence coordinated across various regions of India, put together by Savarkar and published as India’s First War of Independence. The book was promptly banned by the British looking at the emotions it stirred across India. Ironically Savarkar’s book was banned in England and Nehru’s books were published and sold in England, with Krishna Menon as the latter’s Literary agent in England.

The story touches on the fear among the British in 1907-1908 as the Fifty years Anniversary of the Revolution of 1857 came up and activities in the India House. A number of articles celebrating the first national uprising were published by the Indian Sociologist brought out by India House. On the 9th of May, 1907, Lala Lajpat Rai and Sardar Ajit Singh were arrested and deported to Burma by the British Government fearful of a repeat of the rebellion. The record of David Garnett, a young Irish revolutionary from those times who visited India House and met Savarkar in 1909 mentions the environment in the India house where he mentions Savarkar reading a chapter from his book and the moved audience, after the reading going to another room and sit poignantly listening on the Gramophone Vande Mataram.

Coming back to this book, we have Bhagat Singh devotedly listening to the inspiring story of India House. He and along with him, we the readers, learn about the first movement to boycott the British Clothes in Pune organised by Savarkar on 2nd October 1905, under the guidance of Tilak and supported by the Brahmins of Pune at Mahadev Temple of Sardar Natu (Gandhi is still in South Africa and yet to support the Zulu War of the British). We learn about the founding of Mitra Mela, a revolutionary group Mitra Mela, a front for the revolutionary organisation Rashtrabhakta Samuha under the code name- Ram Hari, by Savarkar, still a school child.

The narrative-builders of independent India who often pose as historians do not speak about this phase of Bhagat Singh’s life. This does not go well with their motive of setting Bhagat Singh in the mould of a staunchly communist and mildly Hindu-hating revolutionary. Bhagat Singh was sent to the DAV because students in Khalsa school of Lahore were made to sing prayers praising the British Empire. Bhagat Singh joined DAV in 1917. The College which forms the backdrop of this book is affiliated with the Punjab Qaumi Vidyapeeth founded by Lala Lajpat Rai and Bhai Parmanand.

Acharya Jugal Kishore who also appears in the novel carrying the story forward was the Founder-Principal of the College. While we have no way of knowing if the story was indeed narrated to Bhagat Singh as a student as it is detailed in this book, what we do know is that Bhai Parmanand who tells the story of Savarkar who wrote the book on the 1857 revolution was also sentenced to death 1915 in the first Lahore Conspiracy case for writing History of India. After his death sentence was commuted, he was sent to Andaman, like Savarkar was sent in 1911. Bhai Parmanand was released after Five years in Andamans, having served hard Labour in the prison. While he was away, his property was forfeited by the British and his wife lived in penury supporting two of his young daughters with a monthly salary of Seventeen Rupees a month as a vernacular teacher in Arya Samaj Primary School. Both his daughters died, one in childhood, the other later in her early youth as he writes in ‘The story of My Life’ due to the hardships she suffered as a child.

Bismil’s mother also faced similar penury after he was martyred by the British. Somehow Congress leaders managed to escape this misfortune which everyone considered the enemy of the Empire had to face.

As I have mentioned, while we cannot verify the story itself, which I would call a literary tool, to tell the truth, I can say with some authority that the incidents which form the narrative in this fiction are nearer to the truth than the fiction which is taught in our country as History. It is accepted by almost all historians that this particular period left an indelible mark on Bhagat Singh’s later life as a revolutionary. We do not often talk about it because it brings forth uncomfortable aspects of his life like his admiration for Savarkar.

As the politics of India had evolved post-Emergency and with the leadership of the current Congress alienated from Indian emotions and ethos, there have been huge attempts to push Savarkar away from public memory and attention and to use one exceptional son of the motherland, Bhagat Singh to short-sell another great patriot, his hero, Savarkar, is an ingenious tool deployed for the purpose. We can say with some certainty something of this kind must have happened when we read what Bhagat Singh wrote on Savarkar on the 15th of November, 1924- “The Universal lover is that person who we shamelessly refer to as a violent revolutionary, and a hardcore anarchist- the same Veer Savarkar, who would stop walking over the grasses lest the soft blades of grass might get crushed under his feet”.

Bhagat Singh’s disenchantment with Congress leadership also comes to the fore when in a series he wrote on the revolutionaries, paying tributes to Madan Lal Dhingra he writes in Keerti in March 1928, “Indians organised big meetings, made big speeches. Many big resolutions were passed. All condemning Madanlal Dhingra. But at that time, it was only Veer Savarkar who openly supported Madanlal Dhingra”. Gandhi had condemned Madanlal Dhingra, in 1909 while in South Africa then and had written- “India can gain nothing from the rule of the murderers, no matter whether they are black or white.”

This is not a book of one-upmanship between one freedom fighter against another. It is simply an attempt to bring forth inconvenient truths. We need more such books to be written and read across the board. We must fight against the zeal of current politicians to create villains out of those who suffered for their desire to serve the motherland. The contents of the book are backed by a long list of references. The only way to fight lies is through facts and this book by Manish Shrivastava scores high on facts. We owe it to those of our leaders who have been pushed to the shadows’ of forgetfulness in order to honour politically important ones. The sincerity, honesty and simplicity of the writer stand out in this book. This is a must-read. And reading this will be a true tribute to our patriots in this Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav.

Image source: Indica Today

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. MyIndMakers is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information on this article. All information is provided on an as-is basis. The information, facts or opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of MyindMakers and it does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Comments