Mercantile Collaboration in Different Regions – Gujarat

- In History & Culture

- 01:26 PM, Mar 05, 2017

- Kirtivardhan D,Shanmukh, Aparna, Saswati S, Dikgaj

Editor's Note: This is part 6 of the series on Indic Mercantile collaborations. Here is part 1, part 2 , part 3, part 4, part 5 of the series.

In the previous set of articles [33], [34], [35], [36], and [37], we focussed on the modus operandi of the merchants, their socio-religious characteristics, their mercantile nature [33], and the effects of their collusion on the people of the country at large [34]. We also focussed on the pathetic condition of the peasants and artisans, who were fleeced by both the rulers and the merchants [35]. We focussed on the ways in which the traders financed the invaders, and their involvement in enslavement and sale of Indics to distant regions [36]. We also narrated the deleterious effects their collaboration with the invaders had on the common people, who were often forcibly converted, and/or starved and died in swathes in famines [37]. However, a regional picture was elusive in those articles. Consequently, in the current set of articles, we look region by region, and provide a perspective of the collusion by the traders and how they affected the commoners. In this article, we begin with the mercantile collusion in Gujarat.

Section A: Introduction

From the earliest times Gujarat has been the coastal trade gateway to India, from Bharuch (Broach), to Cambay, to Surat. While it is true that in many ways the decline of one of the Gujarati ports has fuelled the growth of the other, the importance of merchants and trade in Gujarat cannot be overstated. Its geographical location, the numerous rivers that run through mainland Gujarat, namely Sabarmati, Mahi, Narmada, and Tapi, coupled with the richly endowed ‘goodly land’ of Saurashtra has, from the earliest ages, drawn foreigners to Gujarat. Some like the Parsis and the Navayat Musalman came to seek refuge from the devastation of Persia caused by Hulagu Khan, others came as either conquerors or as soldiers of fortune (maritime traders) and stayed back as conquerors and oppressors (British, French, and Portuguese). Some like the Greeks, and Scythians came by land; others like the Turks and Sanganian pirates, came by Sea. p.1, [1].

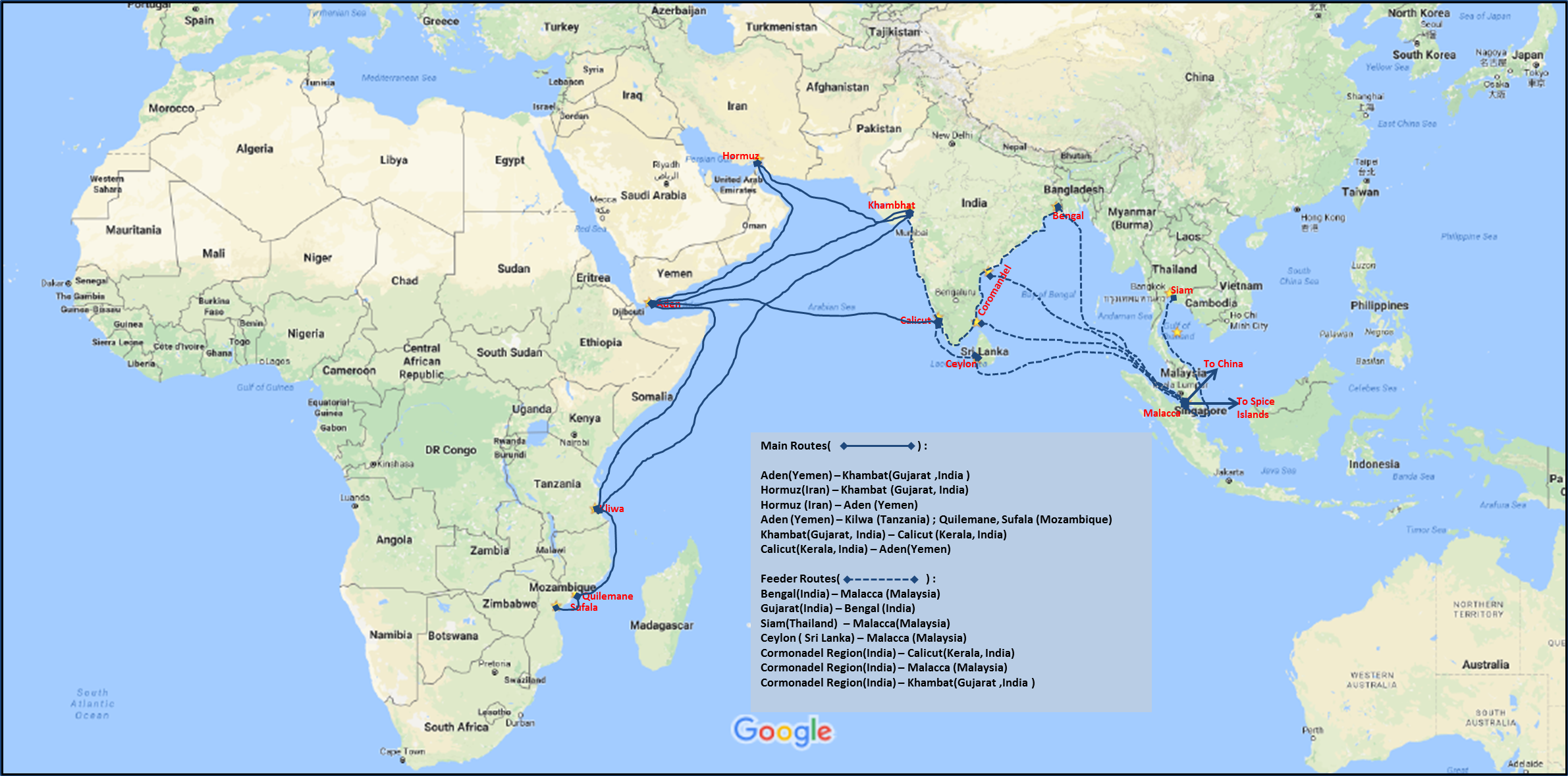

The most important `international’ trade routes in Asia around 1500 AD were: from China and Indonesia to Malacca; from Malacca to Gujarat; from Gujarat to the Red Sea; from Malabar to the Red Sea; from Gujarat to Malabar; from Aden to Hormuz; from East Africa to Gujarat; from Gujarat to Hormuz. The feeder routes linked places such as Ceylon, Bengal, Siam, and Coromandel to the trade centres like Malacca, Calicut, Cambay, Hormuz, and the Red Sea. The most important merchants on all these `international’ trade routes with only two exceptions were Gujaratis. They carried cloths, indigo, opium, and spices. p.10, [2]. As Om Prakash writes, ``Gujarat was a major trading area in the subcontinent and the Gujaratis had traditionally been a dominant group among the Indian mercantile communities. Over the course of the fifteenth century, the trading activities of this group increased to a point where it emerged probably as the largest of all the groups engaged in trade in the Indian Ocean.’’ p.216, [5]. Jean Aubin remarks, Gujarat was the ``keystone of the commercial structures of the Indian Ocean’’ .p.24, [6]. Such was the prosperity of those days that Bharuch became a Gujarati proverb -ભાંગ્યું તોય ભરૂચ roughly translated to even a plundered Bharuch, a shadow of itself, flourishes.

The Baniya (trader) ingenuity could not be limited to trading from Gujarat’s own ports; they set their eyes far and wide to conquer international trading routes. We see that Gujarati merchants settled not only on the ports of the Red Sea, like Sana, Beit al Faqui, Hodeida, and Lohaya, but also in inland towns like Tais and Zabid. Mocha (on the Red Sea coast) and Surat were very closely economically linked. The coffee trade was funded by the Gujaratis and to help the trade, the Gujaratis designed a Yemeni dollar, which was valued 21% less than the Spanish dollar. Loc.194,[28]. Wherever they went, they would establish their own residential quarters. As early as the fifteenth century, Hormuz, like Melaka and Aden, had a quarter for the Gujarati Baniyas. loc. 823, [28]. The same is seen in Thevenets writings in the late seventeenth century, who held the Gujarati merchants in high esteem, and commended them for their skills in the currency business. Thevenet states that he saw some ‘1500 Banias in Ispahan’ (the capital of Persia) who operated exclusively as Sharafs (money changers) and money lenders. He pointed out that they had their own residential settlements at Basra and Ormuz where they had also constructed their temples. When he left Basra for Surat he saw 26 Banias on board the Hopwell traveling with him. pp.27-28, [3]. Ever so often, especially in the earlier years of their settlements, they suffered at the hands of the residents, but to them, as Tom Pires writes, “any offence connected with merchandise is pardonable”, p.27, [6] – a sentiment which was conveyed to Gandhi by some Vaniyas of South Africa when he stated, “Only we can live in a land like this, because, for making money, we do not mind pocketing insults …’’ p. 116, [2], pp.83-84, [4]. It is telling that for the traders profit motive trumped even their self-respect. They valued money at the highest levels, being ready to live as second class citizens for it.

The merchant estate consisted of a number of communities, Hindu, Jain and Muslim, however, Hindus and Jains ‘outranked’ the Muslims, or as, Tom Pires put it: “There is no doubt that these people (the non-Muslims) have the cream of the trade”.p.232, [7]. In Surat, in the early 17th century, some of the richest merchants were Muslims, but the Hindus and Jains were far superior in number. p.103, [2]. Here we see two interconnected points which speak of their mercantile mentality. First, a point which has been alluded in this series time and again, is how they lived in close knit societies. Wherever they went, they lived in their own residential dwellings. We see, as in the section on Ahmedabad and Javeris that even in Gujarat, they lived in community dwellings (the Zaverivad) and formed Mahajans (what can be thought of as a union in today’s terms). Though their motivation (profit making) was highly individualistic, they succeeded as a community. Living as a community, they would act as per the wishes of the community leader (we see later on how both Virji Vora and Shantidas Jhaveri went on to become community leaders). It also ensured that they could shut out members at will, using social expulsion as a tactic. The best example of using societal norms to their benefit is caste restrictions put on foreign travel in the British era. This stance which would seem surprising, was actually hypocritical because, since the earliest times Gujaratis not only travelled across what came to be known as the Black seas, but also established their residential quarters in Arab and South East Asian countries. p.18, [3]. These restrictions seem to have been put to dissuade others from going abroad and competing with the more prosperous traders who had already gained a foothold in those countries.

There also was a mass migration of Gujaratis, as with the advent of the Sultanate, came opportunities for speculating in revenue collections, providing loans and capital to nobles and Sultans. p.128, [2]. It is unsurprising that they were spread across the length and breadth of the country; travellers and merchants like Francois Pyrard, one of the earliest French merchants to visit India talks about the opulence of Cambay, and writes how, ``The principal nation and race there are the Banyans who are in such numbers that one speaks only of the Banyans of Cambaye ; they are found in every port and market of India”. p.25, [3]. Gujarati businessmen were held in high esteem by travellers and merchants like him and Thevenet. He goes on to write how ``The language of all those countries, as also of all others belonging to the Grand Mogor, and of Bengala, and those neighbouring thereto, is the Guzarati language, which is most widespread and useful, being understood in more places than any other Indian tongue”.p.12, pp.25-26, [3]. Which is evident if we look at trade data from Bengal to South east Asia, Maldives and Sri Lanka , though, the Muslim merchants clearly outnumber the Hindu Baniyas in sheer numbers, they were only marginally ahead when it came to number of Ships operated. The trade was dominated by the Shahs of Gujarat, led by Khemchand Shah and Chintamani Shah. p.451 [14]. It is not surprising that the travellers and foreign traders spoke so highly of the traders, for they were at their best moral behaviour while dealing with foreigners, such that their `measures and weights would turn by a hair of the head’. p.141, [8].

The indoctrination, so to speak, happened early in the life of a Vaniya child. They were taught mathematics at an early age, not because of any love for the subject, but to train them, and train them early for a future in trade. Jean Baptiste Tavernier, whose six voyages to India spanned the middle decades of the seventeenth century was impressed by their training. He writes, ``They accustom their children at an early age to shun slothfulness, and instead of letting them go into the streets to lose their time at play, as we generally allow ours, teach them arithmetic, which they learn perfectly, using for it neither pen nor counters, but the memory alone, so that in a moment they will do a sum, however difficult it may be. They are always with their fathers, who instruct them in trade, and do nothing without explaining it to them at the same time.’’ pp.27-28, [6]. A trained child was looked on with great pride, as they (for all practical purposes, it would be a boy who got this training) would then be made to join the trade at an early age and thus generations of mercantilists were (are) seen till date having a long heritage (Pedhi) of trade as something to be proud of. It is an interesting point that the mathematical ability was taught not as a quest for knowledge, but as a tool of trade.

This raises a pertinent question as to who were the Baniyans of Cambay, Broach or Surat. Medieval traveller accounts do not give us a definite answer. Travellers like Ibn Battuta had a very interesting way of referring to all merchants as Baniyas and the rest as Kaffirs or infidels. Yet as we go through the business houses of the Mughal period, we see numerous cases of caste fluidity. To say that business and money making activities were exclusively practised by the members of the traditional trading castes would be incorrect. It doesn’t mean that the castes did not impose any restrictions, but they rarely came in the way of an individual’s choosing of a particular profession. We have enough evidence to show that, in the medieval period, numerous Gujaratis belonging to non-trading castes took to business to take advantage of the available opportunities. East India Company Brokers Somji Chitta and Chhottadas Thakur were Rajputs, and Venidas and Dayaram, like Arunji Nathji Travadi (Trivedi), a renowned Shroff of Surat, were Brahmins. pp.18-19, [3]. An early nineteenth-century report described the term Vanee or Vaneeya as a settled or itinerant trader applied `to any caste following this profession and is not properly speaking a distinction of caste.’ p. 475, [29].

It must be seen that the fluidity extended both ways. The best example is Gandhi’s grandfather who is often believed, rather incorrectly, to be the only Bania to have served as the Diwan in a Kathiawar state. p.224, [7]. In Saurashtra, we see evidence of several Baniyas becoming ministers (Dewans) in the different states. p.235, [7]. With different castes entering new fields, an interesting question as to the change in the nature and habits of the particular castes, is raised, which resonates in a story told by Sharpe of ``how Gandhi’s (M.K.Gandhi’s grandfather’s) carelessness had cost Porbandar nearly the whole and certainly the half of Barda hill.’’ p.224 [7]. This story goes to show the vast difference between the warrior and mercantile ethos. The warriors (Rajputs) view loss of territory as insulting, and a proof of incompetence, while to the mercantile Gandhi, British disfavour and the cost of compensation was more important than claiming every inch of available land. p.224, [7]. Perhaps, the clearest example of the above mentioned mercantile attitude to wars occurred in 1451, when Gujarat was being attacked by Malwa. The sultan asked a friend, a grain dealer, what he should do. The merchant’s advice was for the sultan, to put all his treasure and women on board a ship, `and amuse himself fishing at sea.’ The sultan of Malwa would invade Gujarat, find nothing worth taking, and finally, go home again in disgust. Sultan Mohammad was pleased with this advice and actually began to prepare ships. Then, a noble heard what was happening and threatened the grain dealer with death for offering such pusillanimous and influential advice. The dealer replied, ``Sir, you must understand that the sultan has avoided asking the advice of wise and brave men like you. And instead has asked me, a peaceful and timid grain dealer. Clearly the end product is not manly advice.’’ The noble at once agreed with the dealer’s analysis of the situation. p. 116, [2].

While Gandhi, the Baniya, was not ready to give up his innate nature, the Kshatriyas who took on trading roles were far more accepting of their new role and the ethos which came with that. The case of the Kutchi Bhatias, who were at the forefront of the slave and ivory trade, is important in this respect. They belonged traditionally to the Rajput stock, in the pre fifteenth century, and like the Kshatriyas suffixed the words like Raj, Singh, and Mal to their personal names. Like Khashtriyas, they were non-vegetarians and were fond of intoxicants. But they changed their living style after adopting Vaishnavism of the Vallabhacharya sect in the sixteenth century. More importantly they gave up the traditional farming, and warrior tradition, and took to trading so vigorously that they earned a reputation as astute and wealthy businessmen. p.19, [3]. It is seen that the Hindu merchants of Gujarat had mostly converted to the Vallavacharya sect of Vaishnavism. p.26, [2]. The Brahmins and the few Kshatriyas remained Shaivite in the 16th century p.28, [2]. Thus, we see that the Hindu system at that time was flexible enough to tolerate and accept such aberrations and also, that there was no single ideological position. p.19 [3]. What was common across these cases is that, out of all motivations, money and the accumulation of wealth was always at the forefront.

Section B: Mercantilist Gujarat? Au contraire

The opportunities which attracted a Brahmin or a Rajput to trade must be seen as certain amount of popularity of the merchant ethos. Unlike in other parts of India, especially the north, where social ostracism and the making of profit go hand in hand, such that groups which do undertake the practice of trade, develop, over time, traits which allow them to bear any hostilities from their non-mercantilist neighbours Baniyas, scholars believe, were not considered outcastes in Gujarat. p.225, [7]. On the contrary, many scholars believe that the rank order is reversed in mainland Gujarat – the Kshatriyas being replaced by the Vaishyas. pp. 228-229, [7]. This academic interpretation of society in Gujarat is rather popular with contemporary literature and media having assimilated it into their routine, showing Gujarati society as mercantile. This theory further receives a further impetus with Gandhi, who drew sustenance from a mercantile capitalistic ethos. This reading, though acceptable at first glance is problematic, if studied in detail, as contemporary historians have used Sanskrit sources of Jain businessmen turned ascetics, which were favourably disposed to the business classes (a point explained in detail in Section C). Similarly foreign travellers also held businessmen in high regard as they were also, in many cases, the first point of contact for these travellers. The implication of accepting this explanation points to societal norms being explained without taking into account the behaviour and preferences of the rank and file, ala proletariat, which, in this case, would be the artisans and the peasantry.

The above interpretation, thus, doesn’t hold true if we are to take folklore and folk poetry, especially from the Kathiawar peninsula, into consideration. In folk narrative, we see a completely different image – one of an oppressive Baniya vs a heroic Baharvatiya or an Outlaw. The peninsula has a long oral history of outlaws. The outlaws were mainly disillusioned Kshatriyas who had taken up arms against the oppressive state and the Baniyas. Their modus operand was to loot them (the state treasury and the Baniyas) of their wealth and then distribute it amongst the peasants, the tribes, and the Brahmins. Their methods are best conveyed by a few lines from the Charans (a tribe which lives near Gir and are famous for their poetic flair) who coincidentally were meant to sing praises of the outlaws, wrote:

“They were Waghirs strong and tall and they climbed the loop holed wall;

Then was heard the Baniyas’ wail but their tears had no avail,

When the King of Okha looted Kodinar,

Then a mighty feast he made for the twice born and the Dhed,

And the sweet balls they were scattered free and far,

Though the Brahmin ate and ate, yet he emptied not his plate,

When the lord of Gomti looted Kodinar"p.39,[21]

The above poetry tells us one of the many stories of the Waghirs of Oakhmandal, who would loot the Baniyas and then distribute their spoils amongst the Brahmins and the poor. Most of these outlaws worked based on the principles of natural justice. Unlike the oppressors, they wouldn’t touch women and children. They would neither loot, nor attack the peasantry or artisan classes; their wrath was restricted to those who had wronged either them or the people. Successive regimes used the ploy of villages supporting the outlaws to further abuse the villagers, who in turn would become rebels and take up arms. The concept of Baharvatiya or rebellion, though remembered with great affection in Gujarati folklore, also became fronts for the ruling classes. During and post succession battles, they took up outlawry and persecuted the villagers. By showing martial strength, they hoped to win back the throne. Such instances which occurred were met with severe punishment, usually death, as shown in another one of these poems:

“Carts you robbed of every pie,

As their way they wended;

Thus your scores of crimes ran high

And you badly ended.

Banias fat and short of breath,

Those you rightly looted.

But you robbed a Charan.

Death,To such sin was suited”.p.54,[21]

We later see that, in those times, a large part of the population was extremely poor, and could barely make their ends meet. Thus, most of the peasant class would end up in the clutches of money lenders, who were notorious for charging extortionate interest rates. This led often to a situation where, because of inability to pay anything more than the equated interests, the principal remained unpaid and the moneylenders would slowly take ownership of the land, making the peasants, who had no option but to oblige, landless labourers. In these transactions, the only documentation which existed were the account books which remained in the hands of the money lenders. The looteras or Baharvatiyas would attack the Baniyas, (who also doubled up as moneylenders and thus are used synonymously in folk literature) and burn their books of accounts, destroying any trace of such transactions. These events were celebrated because of their implication, which was, the land being returned to the hands of the peasants. [22]. That there was little love for the big merchants is shown by the behaviour of the commoners and the poor in the wake of Shivaji’s raid on Surat. Shivaji attacked the ‘larger houses’ p.200, [32] and, as soon as Shivaji left, the poor people ‘fell to plundering what was left’ p.201, [32].

Another reason for the deep distrust of the trading classes was their greed, which made them resort to unfair practices. They tried everything possible to cheat their domestic (Indic) customers, who were always at the receiving end of the traders’ unscrupulous practices. Fraudulent weights and adulteration were the norm, rather than the exception p.141, [8]. We see that the peasants were naturally unhappy with the behaviour and activities of the merchant class. What is noteworthy was the merchants’ dealings with foreign traders was very different from those with their own people. The foreigners spoke highly of the merchants honesty. The scathing folk poetry is hardly surprising given the traders behaviour.

This brings us to two different paradoxes which are an offshoot of societal behaviour in those times. First, we see the vast difference between religious literature – especially Jain religious literature, which glorified businessmen and their deeds (detailed description is given later on in this article); and folklore or as it’s called in Guajarati ‘લોકસાહિત્ય’, which shows great contempt for the trading (mercantile) classes. It is evident that this literature was one written by the collaborators of the oppressors and didn’t speak for the people. Similarly the second paradox is regional, between mainland Gujarat and Kathiawar peninsula. The peninsula, which came under the Islamic rule later (which also corresponds with the rise of the Baharvatiya tradition), and didn’t have such a politically powerful mercantile class. Here we see frequent rebellions, while in mainland Gujarat; which had a much stronger bourgeoisie, and was under the direct Islamic rule for a longer period, incidents of outlawry are more exceptions rather than the norm. We see a strong correlation between a powerful mercantile class and Islamic rule. On one hand, rebellions were often crushed, while on the other we see one of bravery, which manifested into outlawry and in many ways defeated one of the strongest collaborators of the Islamic rule-the Mercantilists.

However, it is interesting that in Gujarat, the supposed home of the mercantilism, it was the outlaws who were more in tune with the common people and not the merchants. The outlaws were celebrated by the people at large, while the merchant and his predispositions were vilified. Human nature and repulsion of greed, thus, remain a constant.

Section C: Mercantilism & Religion:

The Jains were another large community with deeply penetrated into business. The great merchants of Gujarat were Hindus, Jains and Muslims. Among them, the Jains and Hindus far outnumbered the Muslims p.25, [2]. Further, there is also evidence of there being numerous Jain millionaires. With Jain business, we face an interesting paradox, for the very tenets of their religion are based on the concepts of non-possessiveness and freedom from material wealth. Yet we see a contrast. The large businessmen, like Virji Vora and Shantidas, who not only belonged to the Jain community, but were also community leaders of a religion which stressed on `Aparigraha’ (non possessiveness) and asceticism. Both of them amassed enormous wealth, and used it as much for enhancing their personal and familial status, as for propagation and strengthening their religion. p.18, [3]. The intermingling between Jain business and Jain monks as seen in those times is common, for the Jain monks needed the businessmen as much as the businessmen needed them. They served as mutual feedback or, if we were to put it more crudely, quid pro quo. The business magnates donated money for preserving and repairing old temples, building new temples, setting up Pathshalas (places of learning), monasteries, and organizing free pilgrimages for members of the Jain fold. In return, the monks eulogized rich Jains in the religious literature. p.18, [3].

We see that most of the Jain ascetics of that day and age like Hirvijayasuri, Siddhichandra, Vijaysensuri, Vivekharsha, Shantichandra Upadhyay, and Lakshmisagarsuri, who had established strong links with the political authorities, under Akbar and Jehangir, were either merchants themselves or they came from business families, before they turned ascetics. They were not `merely men of letters but men of affairs as well’. p.98. [3]. Some of them were proficient in Persian language and the courtly etiquette. It is thus important to note that as Audrey Truschke writes, “the starkest difference between the two communities [Brahmins & Jain Intellectuals at the Mughal court] is that Jains wrote voraciously about their time at the Mughal court, producing numerous Sanskrit narratives and thousands of pages of written pages on their imperial experience. In contrast Brahmins maintained a nearly complete narrative silence on their parallel activities”. p.21, [17]. The works of these businessmen turned ascetics have long been a source for contemporary historians to glorify Mughal rule and the ‘cultural integration’ which took place. They conveniently ignore the quid pro quo between the religious leaders, who time and again, used their influence at the Mughal court to further their interests, and the rulers for whom these businessmen were financiers.

The contemporary Gujarati sources show beyond doubt there was a close collaboration Jain monks and businessmen. p.98, [3]. Businessmen’s wealth was used to preserve pathshalas, temples, old scriptures and also to build new temples and for organising pilgrimages for the poor. On the other hand, the monks travelled widely and popularized Jain religious and ethical values. They reinterpreted religious literature and created new literature. p.98, [3]. The Jain religious literature of the 16th and 17th century show that the monks who had `forsaken’ this world were full of praise for rich businessmen. They eulogized their industrious and frugal habits, simplicity and austerity. Being scholars and genealogists, they did not forget to trace the success story of the merchants’ ancestors. It was as if they were the personal biographers of the Jain businessmen. To put it succinctly, the Jain monks and businessmen served as a mutual feedback and this tended to create and develop the Jain religio-business ethic. p.98, [3]. The best examples of this ethic is that the Jains who wanted to take Diksha (to renounce the world to become monks) had to seek Virji Vora’s permission. Virji Vora first checked their knowledge of Jain religious literature and gave his assent only when he was satisfied. p146, [2]. Another glaring example which has been alluded to in this series of articles is the interference of Shantidas Jhaveri in appointing the Acharya. Shantidas Jhaveri used his wealth, his position, and his status in appointing his friend, Rajsagarsuri, as the Acharya of his sect, despite opposition from Vijayasensuri, the renowned religious leader. Shantidas manipulated matters in such a way that he succeeded in enthroning Rajsagarsuri as the Acharya in 1620. Rajsagar, on his part, remained loyal to his patron and glorified him in several ways after attaining high religious position. p.18, [3]. The Jain monks and business together were able to create a pressure group on the Mughal and then the European administration for furthering the material and spiritual cause of their community. Reiterating what we wrote in the addendum on intellectual and mercantile collusion ``the `establishment scholars’ - both those in the religious establishments and those in the train of the rulers, nobles, and the merchants – became part of the establishment because they were compromised. The compromise of the scholars was a requirement for them to be part of the establishments. The scholars in their train echoed their agenda, as they could not contradict their politico-religious masters while remaining part of the establishments. Undeniably, this is compromise of integrity and abdication of responsibility on part of the scholars, but the point here is only those who satisfied these characteristics were given space to conduct their discourse by an establishment maintained by rulers and merchants.’’ [27]

Jains have an interesting concept of fund raising which in Gujarati is known as Boli (Bid); the practice is especially visible at Paryuṣaṇ is the `Bolī’ or Religious auction. Jains bid for the privilege of performing certain rituals or of supplying the materials needed to run a temple. The public auction is a prestigious way to fulfil the Jain religious obligation to support Jain institutions. Though Jains are not required to make public donations, the public nature of the Paryuṣaṇ auctions encourages everyone to donate and helps to glorify the tradition at the same time. [18] When everything is for sale, even the last rites of a Jain monk are not spared. Recently, in July 2016, the rights to conduct the last rites of Jain Monk were auctioned for Rs.7 crore [19]. Such public spectacles serve to show how deep the erosion of moral values is. As Sandel puts it , market values entering everyday life has the effect of precluding the not so well off from what they consider to be the great service to Mahavir. It also brings in an unhealthy competition in a place of worship, where the rich try to outdo each other. There exist songs like ``Keep the bidding going, someone bid. O my Jain brothers, call out large bids! My Jain brothers, then no one can find fault with you.’’ p.285, [20]. Kelting explains that the charity auction (like art auctions, which also affect the status of the buyer) is a ``site for status negotiation and the assertion of social position.’’ p 287, [20]. Such auctions play an important role in determining the social status as well as the credit worthiness of a Businessmen. Haynes found that Gujarati Hindu and Jain merchant castes (collectively, Vaniyas) in Surat linked creditworthiness, reputation, and virtue to public donation, in particular, to religious donation - even when they made philanthropic donations in order to secure status with outsiders. These public donations proved both the donor’s virtue (by indicating a commitment to the shared moral values of the merchant communities) and the donor’s position as patron of his religious community. Merchant castes act in ways that mark them as merchants, while, at the same time, features of that identity are articulated in particular religious contexts like the Jain auction. Babb argues that Jain gem manufacturers’ articulate virtue and trustworthiness as merchants rather than as Jains, but their status as trustworthy person is linked to their performance of Jain identity. In their performance of the values attached to reputation, creditworthiness, and public religious donation, Jains can be identified with the socio-economic community and strategies of merchant culture in western India. p.290, [20]. One’s bidding at grand, public Jain auctions is crucial to the self-presentation of those who wish to be major players in the congregation. These bidders craft their identities on the model of the patron or leader of the congregation (Sanghpati). Jains have a long history of great lay donors, and grand donations in Jainism have been central to the construction of Jain notions of masculinity. In winning the auctions themselves, Jains identify with the role of religious patron. p. 291, [20]. These overtly religious events have the effect of creating a class hierarchy for both the religious leaders and the worshippers. Where a person’s religious devotion is valued solely in terms of monetary worth, they encourage the narrative that money must be earned, even if by exploitation or immoral methods, to survive in such a cut throat society.

Despite their overtly religious behaviour we see that their moral standards when dealing with Indic customers were extremely low, be it their weights, p.141 [8] or even in their treatment of the artisans (elaborated in the section below). We see that such grand religious display is just an act while in reality they were ready to trample over the poorer sections of the society.

Section D: Mercantilist Behaviour across Regimes

Trade was an integral part of society in Gujarat much before the advent of the Islamic rulers. Traders, even more so, were an important lobby since early times. Islamists who went on to rule India, much like their European counterparts, first got a foothold as traders, especially in marine trade from the coasts of Gujarat, and it is said that Jain merchants who exercised considerable authority and enjoyed immense power, may well have encouraged Siddharaja and other rulers to treat their Muslim counterparts generously.[26]. In the next two subsections, we indicate the amount of power wielded by the mercantile houses and groups in the Islamist regimes of the Gujarat Sultanates and the Mughals that followed them. The wealth and power of the great mercantile houses spanned different kings often, and constituted a strong backbone of the Islamist power in the region.

Part 1:Gujarat Sultanate

Cambay was at the heart of the Sultanate of Gujarat, divided into ten territorial administrative units called Sarkars. Outside of Cambay but within the Gujarati state in Kathiawar, lay Kutch, Malwa and Rajputana, and the south of the Tapti River. They were economically peripheral and in other respects quite distinct. Cambay and its production of Indigo and cotton is what made Gujarat famous, and it is there that the capital of Ahmedabad was located. The rulers had a deep interest in the success of the trade as it was a very important element in the economy of the Sultanate. The Muslim rulers provided them (the traders) protection and were ready to let them be as long as they continued to contribute to the coffers of the state. p.25, [6]. The sultanate of Gujarat produced a great deal of opium. p.25 [2].

Before we can talk about the Sultanate’s rule over Gujarat, we see eye opening behaviour of the Nakhudas (both Hindu and Jain), or the ship owners, which is best explained with a story. During that time, there was a marked rivalry between the Delhi Sultanate and the Caulakya Kingdom in Gujarat. Vastupala (a famous merchant and a minister of the Caulukya ruler, Viradhavala), was made aware of the Haj pilgrimage the old mother of the Delhi Sultan Muijuddin planned to undertake. She stayed at the premier port of Gujarat, which was also noted for its annual hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, as the guest of a ship-owner. Vastupala made his men rob the mother of the Delhi Sultan of her entire belongings. The theft was then reported to Vastupala by the ship-owner. Vastupala paid the Sultan's mother profuse respect and assured her that her property would be found. He then returned it to the old lady who was immensely touched by his kindness. After her successful and safe return from the Hajj, she was eager to reward Vastupala, which was what he wanted in the first place. She, then, took him to Delhi as her guest and introduced him to the Sultan and another one of her sons. Vastupala then asked for permanent friendship between the Delhi Sultan and the Gujarat king as his reward. p.59 [9]. The message conveyed is of close linkages, between the Sultan's family and a ship-owning merchant, who must have been a leading shipowner. The Gujarati epitaphs in Arabic, cited above, often eulogise Nakhudas as the mainstay of the Hajj pilgrim. There were numerous ships operated by the Arabs, Persian and Turks, but the bulk of the trade was controlled by the Gujaratis. p.444, [14]. The story in question might suggest that they also provided substantial assistance to the foremost Muslim royal family of Northern India. pp.58-59, [9].

We can see a link and communication between the merchants of that era and the Delhi Sultanate. Thus it is not surprising that the merchants continued to be a strong lobby under the Gujarat Sultanate from the late thirteenth century onwards. As K.A.Jacobson opines, ``The strong position of the merchant means that Gujarat may have been the first Indian region to develop a veritable bourgeois.’’ p.272, [10]. The merchants had their reach much beyond simple lobbying; they were also major funders of the Sultanate. In 1509, Malik Ayaz, Governor of Div, was able to raise Rs.6,50,000 from his own resources and those of the merchants of his town. p.28, [2]. Rs.6,50,000 would be an astonishing figure in those times. Just for context, that would be more than twice the land revenue realized in those years. Gujarati businessmen were also important money lenders to the nobles and sultans. As Ashraf writes, ``A whole of class of people from both communities [Multanis and Gujarati Banias] began to thrive on the business of lending money. These Sahus and mahajans, as money lenders and bankers were called, were extremely popular with all the upper classes whose extravagance and constant demand for money were proverbial.’’ p.140, [8].

Though, mostly, it was the Muslims who could get access to political offices during the Gujarat Sultanate, there have been several instances where Hindu merchants could get similar positions. In 1560s, a noble appointed a Vania as his minister, who was entrusted with supervising his trading activities. In the early 15th century, two Vanias became officials of the Sultan. p.129, [2]. The case of Malik Gopi, the Brahmin trade administrator, who dominated over Khambayat (Cambay), which was his privileged area of interest, went on to become the Governor of Surat is an important case in point. p.24. [11]. A later work based on oral traditions prevalent in the nineteenth century, Ras Mala, refers to several instances of Bania merchants employed in the service of Gujarat state. p.40. [12].

Those were times of great prosperity for the merchants .As Majudar writes, ``The numerous wealthy merchants and skilled craftsmen living in the city (Amadabad ) led a luxurious life of pleasure and vice and were accustomed to good food and clothing…Among the Hindu castes of Gujarat, the Baniyas had orchards, fruit gardens and tanks in their house.’’ pp. 655-666. [13]. Contrast that with the lifestyle of the humble peasant who according to Ashraf, ``In return for all his labour he was lucky if he could obtain a square meal every day. There are very few and very vague references to the life of the peasants, but it can be asserted with confidence that their lot was miserable and they lived constantly in a state of semi starvation. And that the possessions of a [peasant] family are limited to a couple of bedsteads and a scanty supply of cooking vessels.” p.124, [8].

Part 2: Mughal Regime

In the Mughal regime, coastal trade remained as important as during the earlier times, if not more so. Several major Baniya merchants operated from ports, both in Gujarat and Bengal. Khemchand Shah and Chintamani Shah were two major traders from the Balasore port. Traders from Surat had an extensive network of agents and correspondents all over the Persian Gulf and Red Sea region. The agents of the traders from Gujarat, who were also Baniyas, lived in those places for extended time periods. An even more important role was that of facilitators providing export goods to ship owners and other merchants. Two groups greatly depended upon the services of these merchants. First, the Mughal nobles and officials, for whom these merchants were agents, and brokers to whom the decision making was left. Second, the European enterprises and private European traders, who purchased export goods from the Baniya merchants and sold them the import goods. p.437, [14]. As Lakshmi Subramanium writes, ``The Banias, with their long trading lineage, had been adept at exploiting the situation, and very soon virtually monopolized the lucrative business of brokerage and banking. Controlling the supply trade at crucial intermediary levels from the primary production areas to the principal distribution centres inland and on the coast they accounted for a sizeable and probably the most influential section of Mughal Gujarat's commercial population.’’ p.476 [29].

In the Mughal era, we demonstrate the power and influence of the big merchant houses on the rulers, the commoners and the religious establishment. We show that the big merchants were able to stop wars or ignore them with impunity when it was against their interests, obtain several socio-economic-religious privileges from seriously discriminatory Mughal regimes, get rid of officials who were against their interests and control the religious establishments of their time. The merchants were also able to sign treaties on their own account with both the Mughals and the European powers. We contrast the life of the big merchants against the artisans and the peasants and show that the merchants were able to control the economy of the region to their own benefit and against the interests of the peasants and artisans. The biggest houses like the Voras and the Zaveris were able to control the entire economy of the region and wielded immense power with the Mughals, who honoured them. Finally, the biggest merchant houses were so powerful that they were able to escape even extortion by Mughal officials and even princes, when the latter were hard pressed for resources during wars.

Deep Pockets: The famed Gujarati Bankers and their influence

Moving on from extortion to how the merchants funded the Mughals, we cite numerous instances of the Gujarati bankers utilising their power in the Mughal empire. This ranged from funding not only the Mughals, but also religious communities, giving them enormous clout with both the Mughal rulers and their own (and others) religious communities. The mode by which the merchants could control both the rulers and the religious heads had already been established by the bankers of the 17th and 18th century Gujarat.

1) As we have shown earlier, a big role was played by the Gujarati ship owners in the Haj pilgrimages, which in essence goes to the appeasement. This appeasement we see even today. where temple funds are used to subsidize these pilgrimages.

2) The Gujarati merchants, particularly the Hindus and the Jains, donated to all religious establishments. Around 1600, a wealthy Bania of Chaul (presumably a Jain) bequeathed Rs. 60 to each of the Christian confraternities in the city. p.109, [2].

3) Early in 1613, the Portuguese happened to seize a Gujarat ship returning from the Red Sea with the goal of forcing the Mughals to expel the English from Surat. Jahangir’s mother had a large interest in the ship’s cargo. So a war broke out between the Mughals and the Portuguese. So, the Portuguese sent an emissary to Gujarat to invite the merchants to continue to trade to Goa without taking cognisance of the war. The Gujarati merchants immediately swung into action by the end of 1614, and endeavoured to secure peace. They offered to reimburse Jahangir the value of the goods seized by the Portuguese, hoping thereby that the dispute would conclude and they could resume trade. Peace was indeed concluded in 1615 and quickly ratified by the Portuguese Viceroy. Jahangir did not ratify the treaty, but the merchants enthusiastically resumed their trade. Historian Pearson provides an interesting analogy for this incident – he finds it equivalent to American businessmen with Japanese trade interests offering to pay full compensation to the United States after Pearl Harbour (The latter incident didn’t happen, but is an equivalent scenario).p.120, [2].

4) In the 1650s, the Mahajans of Ahmedabad contributed Rs. 60,000 to repair the fort of the city. p. 125, [2].

5) In 17th century Mughal India, when a Mansabdar moved to a new position, he had to provide a security for the performance of his duties. It was usually a merchant who lent to him towards the above obligation. Many nobles, as also the sultan, and the emperor and their families, traded overseas in the ships of the merchants. In addition, the merchants also hired most of the cargo space in the ships of the royalty, nobles, sultan, emperor and their families. p.129, [2]. As seen in the earlier mentioned cases, Gujarat’s merchants regularly provided both capital and loans to both sultans and nobles. p.128, [2]. We will also see in later pieces that loaning money did not stop with the Mughals, but continued with the Europeans, and lastly with the British.

The Mercantile class of Gujarat had immense power as they acted as the ultimate authorities within their groups and also as intermediaries between other merchants and their governments. The officials frequently sought their advice on commercial matters and kept them informed of government decisions affecting the interests of their groups p.126, [2] and more often than not the emperors were ready to bend over backwards to keep them happy. For example:

1) Virji Vora and Shantidas Jhaveri headed profession based guilds or Mahajans, constituted to promote and protect common interests. Ever too often, members of different guilds would come together to meet exceptional circumstances. In 1618-19 when the English and the Dutch pirates looted ships on the Indian Ocean, the Surat Mahajans sought Mughal cooperation to punish the English and Dutch merchants. At the same time, a decision was taken to stop supplying goods to the English and Dutch. On another occasion, the Mughal governor took the initiative and formed a committee of influential Hindu, Muslim, and Jain merchants and government officials to settle an account with the English who had seized two Gujarati boats. pp.22-23, [3]

2) On one occasion (1636), when the Indian ship which carried his goods was sacked by the English pirates, Shantidas retaliated by getting William Methwold and Benjamin Robinson, two of the companies factors at Ahmadabad, imprisoned, p.24, [3] and even when their Bania brokers stood as surety, they were forbidden from crossing the walled city. p.108, [3].

3) The power and the influence of the Gujarati merchants can be seen when one also examines their transactions with the English. In October 1623, three English ships seized 8 Gujarati ships and together they arrived near Surat from the Red Sea. The English action was clearly an act of war against subjects of the Mughal emperor. But the Gujarati merchants negotiated with the Mughal emperor on behalf of the English. So they served as their (English) guarantors and secured good treatment for the English from the officials. The Gujarati merchants even signed agreements to the above effect with the officials. However, later, in January 1624, when all the English ships left Surat, the local merchants then used their influence at the Mughal court to get the Mughal emperor Jahangir to pass a series of farmans against the English. The English were imprisoned and their goods confiscated. Negotiations re-started, but one Surat merchant still deemed fit to take a pass from the English while they were in a Mughal prison. When a final agreement was reached in September, both the Gujarati merchants and the officials again signed it. It is important to note that the Gujarati merchants enjoyed complete autonomy in the affairs that concerned them. p.119, [2], Virji Vora was one of the signatories to this agreement. p. 138, [16].

4) The merchants could also play hardball with the European powers to secure their profits. In 1619, to curtail the competition launched by the English on the Red Sea route, they forbade the sale of any goods suitable for this trade. In Surat, two merchants who disobeyed this general order were imprisoned. p. 125, [2]

5) The mercantile class enjoyed great prestige in Gujarat. They were given important positions like the position of Nagarseth. Shantidas Jhaveri was the Nagarseth of Ahmedabad. p.125, [2]. In 1640 another merchant called Madan Udhavji Parikh was the Nagarseth.

6) We can see from a farman of Shah Jahan how another merchant named Savji Parikh was able to get the tax charged by two Jagirdars, Sayasta Khan and then Mirza Isa, reduced from 6% to 3% and also get an order which forbade any future Jagirdar from increasing the tax rate.

7) That Virji Vora enjoyed high status could be shown by the fact that, after Shivaji sacked Surat in 1664, the Subahdar of Surat sent Vora and Haji Zahid Beg to the Mughal court at Agra to persuade the authorities at Agra to raise a castle around town for future protection. p.59, [3].

8) In May 1636, when Shah Jahan was upset with the high handed dealings of the Governor (Subahdar) Azam Khan, the Ahmedabad merchants rallied behind Azam Khan and were able to get him reinstated.

9) Being a community leader, Shantidas often also acted as intermediary between the government and the constituents of the religious group which he headed. In his role as intermediary, Shantidas was granted royal farmans bestowing on him a village and a hill. p.440, [14]

Wealth and Poverty: Contradictions in Gujarati Society

The lifestyle and the prosperity of the merchants is a major contrast from the way of living of the rest of the population, as the merchants of Gujarat were left alone by the upper echelons of power, in matters concerning not only business interests, but social and religious interests as well. They were completely autonomous in commercial matters. The big businessmen regulated production standards, holidays, interest rates and also their (Mahajan) membership. Most importantly, artisans and employees were left to negotiate on their own with the Mahajan or individual merchants. This provided significant advantages to the merchants, as they were in a stronger position as compared to the artisans and the employees. p.130, [2]. Makrand Mehta elaborates, ``The Hindu artisans came from the lower castes and they were also poor and illiterate. Taking advantage of their helplessness, the Gujarati merchants (Banians ) belonging to the higher caste strata, exploited them by making advance payment for the purchase of the raw material. The Bania exercised his authority on the artisans through the mechanisms of advance money.’’ p. 22, [3]. Be it the artisans of Bengal or of Gujarat, all were under the thumb of the merchants. George Roques of the French East India Company did not mince his words when he spoke about the merchants (unfair) dealing with the peasants and artisans. Roques was unhappy, rather furious, with the way in which the textile trade was being conducted in Gujarat, particularly the role played by middlemen in fleecing the profit margins in the course of transactions. pp.28-29, [3]. But he was not alone in this respect. Many a contemporary traveller and merchant spoke of the ‘knavery‘ and the sharpness of the middlemen, and commonly held that the broker system was the primary cause of the exploitation of weavers and other artisans. pp.28-29, [3]. The lower class workers were regularly exploited by the merchants to give the latter an upper hand in their dealings with the foreign merchants. For example, once, to protect their interests, the Gujarati merchants instigated the indigo workers to botch an English order, such that the English East India Company suffered a loss of2000 rupees. p.29, [3].

For all the lavishness of the merchants, the weavers went on with their life, barely able to make ends meet. Mehta writes, ``The weavers actually received very little cash. What they got was old, worm eaten, decayed corn and some money.’’ p.36, [3]. This was something similar to what the peasants received, for they were always taxed much higher than the merchants. They, like the weavers and artisans, and unlike the merchants, didn’t have trade guilds which had the ear of the successive emperors. We see that the Gujarati merchants were taxed at a much lower rate than the rest of the populace. They paid customs duties of only 2.5-5%, minor inland taxes and some usual bribes. The cultivators paid at least 1/3 of their earnings in taxes. p.130, [2].

As a last example to contrast the situation of the people and the merchants, we look at the Gujarat famines of 1630-1633. An account of the famine of 1630-1633 states that up to 30000 people had died of starvation in the city of Surat, and that a large number, [60%-70% of the population], had fled before death overtook them. P10, [16]. Around the same time, Virji Vora was dealing in more than 12000 tolas of gold, and the best Virji Vora could do was offer grains to a few people from his community. The famine becomes far more important when we look at the accounts of Peter Mundy, where he shows how the famine of those days wasn’t as much a problem of scarcity (there had been a successive drought) as an economic problem. He goes on to write how, ``At Navi, in the middle of the Bazaar, lay people now dead and others breathing their last with the food almost at their mouths, yet dead for want of it, they not having wherewith to buy nor the others so much pity to spare them any without money (there being no course taken in this country to remedy this great evil, the rich and the strong engrossing and taking perforce all to themselves’’ p.49, [23]. The situation was similar throughout. Thomas Rastell’s, President of the English factory, letter shows that, ``no grain was to be had for man or beast, even for payments of seven times the normal prices and that the poor artisans of the province had abandoned their homes in large numbers, and, owing to the absence of all relief, had perished in the fields for want of food.” p.314, [24].

Voras & Zaveris:

We now illustrate how two powerful families, the Voras and the Zaveris, were able to wield enormous clout in the Mughal empire. Ahmedabad was the seat of administration in Gujarat which meant it was inhabited by a large number of officials, nobles, and army personnel. This tended to add to its flourishing trade in gold, silver, ornaments, textiles, and perfumes. Ahmedabad’s importance as a centre of trade further grew with the Mughal conquest of Gujarat in 1573, which was later supplemented by the European traders and the East India Companies’ emergence as buyers of the goods. p.92, [3]. William Finch, an Englishman, wrote in 1611 that, ``Amdavade is a goodly city situated on a fair river, inclused with strong walls and fair gates with many beautiful turrets .. The buildings comparable to any city in Asia or Africa, the streets large and well paved, the trade great (for, almost every ten days go from hence two hundred coaches richly laden with merchandise for Cambay), the merchants rich, the artificers excellent for carvings, paintings, inlaid works, embroidery with gold and silver.’’ p.93, [3]. J. Albert de Mandelso, a German traveller who visited Ahmedabad in 1638 said, ``There is not in a manner any nation nor any merchandise in Asia which may not be had at Ahmedabad.’’ p.93, [3]. Thus, control of trade in Ahmedabad and Surat tended to grant huge advantages to the men who controlled it.

The advent of such large trade in Ahmedabad led to the development of professional guilds of merchants. These Mahajans were not based on caste or class. They were the sole decision makers on matters of admission of new members. They worked to safeguard their members’ rights. Many aspects of day to day business were controlled by the Mahajans. They had an extensive Hundi network and also played an important role in arbitration and dispute resolution. Wages were also decided by them. Time and again they would get together to bring forth their grievances to the rulers. p.93, [3]. A rather unique feature of Ahmedabad was the creation of Zaverivads (i.e. settlement of jewellers). Cambay and Surat both had large trade interests in precious stones, and metals, but we don’t see any mention of separate settlement for the Zaveris. Maganlal Vakhatchand believes that the Zaveris had their own Mahajan, which was controlled by the Jains, who inhabited the Zaverivad and it existed since the seventeenth century. Shantidas Zhaveri is believed to be the head of this Mahajan. Mannucci, who visited India during Aurangzeb’s reign. wrote that there were many people who made jewellery set in stones in Ahmedabad and other cities of Gujarat. His account gives us detailed information about the reach of the jewellery traders. He writes that the ``dealers who give orders for this class of work go themselves or send their agents to the diamond mines, to the kingdom of Pegu, to the Pescaria (that is pearl fishing coast of Tinneyvelly) and other places to buy precious stones they require .All these merchants are Hindu by religion and are called Guzeratis. Their persons are well made and their women always smothered in jewellery.” pp. 93-94, [3]. The professional skill of these merchants was utilized by the Mughal regime to examine the quality of precious stones. Jehangir had a jeweller named Hirachand, who, on one occasion, bought Jehangir a diamond worth Rs. 1,00,000. Travernier, a French jeweller who popularized Indian diamonds and jewels, wrote that, ``Aurangzeb had two Persians and a Banian Nyalchand to help him in purchasing – which was actually often extorting at lower prices – jewels and diamonds.’’ p.95, [3]. Travernier also writes, ``how, in case there was any large diamond to be sold in the country, the jewellers had intelligence of it beforehand.’’ p.95, [3]. Sir Thomas Roe observes that ``the annual trade in pearls far exceeded 50,000 pounds and that the pearls between ten and thirty carets were in great demand.’’ p.96. [3]. Travernier has given a beautiful picture of a diamond which weighed 157 1/4 carets. pp. 93-96, [3].

Shantidas Jhaveri was the first Nagarseth of Ahmedabad and that title, with its attached status and conventional functions, was then handed down in his family for a long time. As mentioned earlier Shantidas was a devout Oswal Jain descending from the royal Rajput houses, the Sisodias of Udaipur, and he had two wives. p.53, [25]. He installed an image of Mahasnath at the holy centre of Shatrunjaya. In 1616, he became a Sanghpati and, in the company of a large number of sadhus, led a Jain pilgrimage to Siddhagiri, where he spent large sums of money in charity. In 1621, jointly with his elder brother Viardhaman, he built the great temple in the suburb of Pibipur at Ahmadabad. Four years later, in 1625, he consecrated the image of Parshwanath in this temple, with the help of the learned scholar Vachakeudnu. All these events are occurred during the reign of the Emperor Jahangir. On the accession of Shah Jahan to the throne, Shantidas received from the Emperor gifts of horses and elephants in 1628. p.54, [25]. In 1645, Prince Aurangzeb who had been given the charge of Gujarat ordered the temple to be desecrated and converted into a mosque. So powerful and influential was he (Jhaveri), that on a representation being made to Shah Jahan, the temple was restored and all costs of restoration were to be borne by the kingdom. p.57, [25]. This farman is interesting because it talks about how property belonging to another when used for a mosque, cannot be considered a mosque according to inviolable Islamic law. p. 58. [25]. The village of Palitana, which is today considered to be one of the holiest sites for Jains, was also issued as a gift to Shantidas by Murad Baksh. p.65, [25]. We go on to see how, in 1660, in addition to Palitana, Shantidas also received a grant of the hill and temples of Girnar under Junagadh and of Abu under Sitohi as a special favour. The farman, however, is clear that they are all given, to him in trust for the use and worship of the Shravak community. p.74, [25].

That Shantidas was a wealthy trader is very well known. He also contracted with the Dutch to provide a supply of diamonds from Golkanda mines. p.96, [3]. He also used to visit and spend lavishly at Bijapur, which was a famous mining and trading centre. p. 96, [3]. The position of Nagarseth also entitled Shantidas and his family to a fixed percentage of the revenue. We see in the later years, that during the Anglo Maratha wars, the descendants of Shantidas who went on to serve as Nagarsheths, not only helped the English by allowing them to use their private mail network, but also paid the army of the Mughals from their own pocket for which Nagarsheth Khushalchand was suitably rewarded. p.XIV, [25]

The power of the other merchant house, the Voras, is demonstrated by using the context of Shivaji’s raid on Surat. In the history of Gujarat, as also in popular discourse, Shivaji’s attack and subsequent loot of Surat has been considered the stuff of legends, the talk of which elicits diverse, yet interesting. reactions. On one hand, inhabitants have more or less viewed those events with great disdain. Shivaji is blamed with the destruction of the richest port of India, a view which resonates across history books. On the other, some view it as an attack on the Mughal treasury, its cash cow, and its supporters. This debate has been exploited by numerous politicians, the latest being current Prime Minister, who declared to a crowd at Raigadh, that it would be insulting to say that Shivaji looted Surat; he, in fact, looted the Mughal treasury with the help of the local residents. [30]. This statement led to historians protesting the accuracy of his statement. Politics and opportunism aside, the events of the two loots i.e, the loot of 1664 and that of 1670, are important because they are closely tied to mercantilist behaviour and their relations with the Mughal authorities as well as the European trading establishments in the city (the English and Dutch Factories).

The sack of Surat was, for all practical purposes, a mission to fund the Maratha armies. Though if we were to believe oral history, they were attacks which were brought about by the refusal of the merchant princes (rich merchants) of Surat to finance the Maratha army. The events, as they took place, do give some impetus to the latter notion. A letter written by the then President of the English council tells us that on hearing the ‘hot alarm’ that Shivaji the ‘grand rebel of the Deccan’ was within 10-15 miles of the town (Surat), ‘the Governor, the rest of the King’s minsters and eminent merchants betook themselves to the castle’ while the rest of the townsmen took their families and left, some on boats and some to the villages on the outskirts. The town they write was ‘dispeopled (depopulated). Shivaji also sent an emissary the night of 5th January with a letter ‘requiring that the governor, Virji Vora, Haji Kasim, Haji Zahid Beg, the three eminent merchants and moneyed men in the town, come to him immediately in person and conclude with him, else he would attack the town with ‘fyre and sword’ pp.298-299, [31]. Shivaji, knowing the wealth and the power of the merchants, was clear that he would deal with them as representatives of the Mughal Empire and we see that, as expected, the eminent merchants were protected just like the ministers and the governor they took shelter with in the castle.

Having received no response, Shivaji went on to attack Surat. Near the Dutch factory stood Voras house. Vora was then ‘reputed to be the richest merchant in the world’. His property was estimated to be worth 80 lakhs. Jadunath Sarkar writes, based on accounts of General Smith (of the English factory), that Voras house was looted of 28 seers of large pearls, with many jewels, rubies and emeralds and an incredible amount of money. p.103, [32]. Iverson, one of the staff at the Dutch factory and an eye witness, states that Vora lost 6 tons of gold, pearls, jewels. He also states that two other Hindu merchants suffered to the extent of 30 tons. William Foster estimates his loss to be 50,000 pounds. p.310, [31]. Both Haji Kasim and Haji Beg also suffered tremendously, as did the other larger merchants like Somaji Chitta and Chota Thakur, who were brokers to the English. p.123, [16]. Writing on January 22nd, the English president and council estimated the total loss to be one crore of rupees. p.303, [31]. Shivaji is said to have spared the broker of the Dutch Factory, Mohandas Parekh, because he was said to be very charitable, especially towards the Christian missionaries, who, according to Shivaji, were ‘good men’ p.310, [31]. The merchants were compensated for their losses both times. The traders who stood and defended the factories received commercial privileges from the emperor p.202, [32]. The emperor also vowed revenge and remitted all the customs (payments from the merchants) and after a year, the customs were to be reduced by one fourth. p. 311, [31].

Extortion or Collusion?

With any sort of financing, especially to oppressive rulers such as the Mughals, there is a legitimate question of extortion raised. Was the help – monetary or otherwise – given under some threat or duress. With state officials having great amounts of power and selfish motives at hand, it is expected that they would use their position to fulfil their selfish needs. As Om Prakash writes, ``It is certainly true that state officials in early modern India, both in the Mughal empire as well as in southern India, did indeed misuse their authority to fleece merchants and other well-off sections of the community. In Mughal India, this was done, as far as the merchants were concerned, by misusing the provisions of farmayish and sauddyi khass among other things. These provisions entitled senior state officials to requisition goods for official purposes at unilaterally determined prices, which were often considerably below the market. More often than not, requisitioned goods were intended for private trade of the officials rather than for public use. Other more direct methods employed included the imposition of the equivalent of an excess profit tax, and even the outright confiscation of the bullion deposited by some merchants at the imperial mint at Rajmahal in Bengal following these merchants' refusal to provide a loan to Shah Shuja, the subedar of the province, to facilitate his campaign for the Mughal throne. Many more instances of this kind of extortion can be quoted for other parts of the Mughal Empire, as well as for regions outside the empire. However, it is critically important to keep the matter in perspective and not overstate either the incidence or the magnitude of such impositions. These were essentially in the nature of aberrations rather than anything approaching the norm.” p.439, [14].

There are two widely cited incidents and the context in which they played will be used to address this, and explain why these were aberrations. Both these incidents revolve around the court jeweller Shantidas Jhaveri, who was given the honorific title of ‘Mama’ by Shah Jahan. Both these incidents played out during times of political crisis; both took place during succession battles. The first occurred in October 1627, following the death of Jahangir. Shah Jahan, who was then a mere claimant to the throne, needed money to finance his army. As described by Nathenial Mountney, an English factor of Ahmedabad, Shah Jahan locked the gates of the city (Ahmedabad) for two days, so that the Baniyas couldn’t escape till they had paid him his demand of 20 lakh rupees. The money had to be extorted because the ‘rich were not willing and the poor unable’. Nathenial Mountney also raises a doubt as to whether the extortion was authorized by the Prince or not. Shantidas the ‘deceased king’s jeweller’ was in the city but was able to privately retire himself. p. 103. [3]. Here we see an interesting phenomena. Even during times of political crises when no one was spared, Shantidas, who would have been the perfect target to extort money from, was able to hide himself, and thus, be spared. The second incident was similar and took place in 1657. With Shah Jahan’s serious illness becoming known, there ensued a war of succession between his sons. Murad Baksh, who was then in Gujarat, looted Surat with the help of Shahbaz Khan. Shahbaz Khan compelled Surat merchants to lend him large sums of money, post which the same was repeated in Ahmedabad, where Murad was successful in borrowing a large sum of Rs. 5.5 lakhs from Shantidas Jhaveri. Jhaveri then went to Delhi and was ‘honoured with an auspicious audience’ and was able to receive a Farman from Murad himself which enabled him to recover his loan from the government. The story doesn’t end here; since Aurangzeb captured Murad, and his farmans were rendered worthless. Consequently, Shantidas made fresh attempts to recover his loan. and he was able to pressurize Aurangzeb into issuing a farman dated 10/08/1658 to pay Shantidas one lakh as part of the loan recovery. p.104 [3]. Again, in this incident, we see that wealthier merchants like Shantidas were able to save themselves by receiving repayment farmans not once, but twice. It cannot be denied that the smaller merchants would have been at the receiving end, but those with political patronage, like Shantidas, had enough ways to protect themselves. Similarly. we see that Virji Vora had fast fluctuating relationships with the Mughal Subedars (Governors) of Surat. The Governors themselves had large, but private, trading interests. For example Mir Musa, the governor of Surat in the 1630’s, traded with the English and often exerted pressure, on Indian and foreign traders alike, to maximize profits. Vora dared not trade in the same commodity (as Musa) as that would lead to Musa offering Vora a partnership, which would adversely affect his own business. Yet it is seen that overcoming his earlier resistance, Vora in 1642 used ‘his potency and intimacy’ with Musa to corner the coral stock and thus monopolizing the trade of coral, pepper and other commodities. When Hakim Sadra was the governor of Surat, he cornered the available supplies of pepper, extorted money from the mercantile community of Surat and also imprisoned Vora. When Emperor Shah Jahan heard of this incident, he summoned Virji Vora, to the court, to explain the case after which Vora was set free and Sadra was removed from office. p.58. [3]. To summarize, the merchants in most cases were happy to go along and in return, ready to put forward their own demands, whenever required. There are numerous instances of how the merchants reacted to hostile treatment and how they were able to win back their privileges and continue unscathed. We cite a few instances to show that Gujarati merchants operated with similar independence throughout in their transactions with the rulers of the territories they functioned in. pp.121-122, [2].

1) In 1546, the merchants felt that the Portuguese in Div, in charge of valuing coinage in the customs house, were acting against their interests. However, they did not appeal to the appropriate Gujarati official in Div, but just retaliated on their own by organising a boycott, and the Portuguese immediately backed down. pp.121-122, [2]

2) Once when a minor Portuguese official was killed in a Gujarati town, and war was threatened in retaliation, the merchants ensured that the status quo was restored by mediating between the two sides. The merchants also guaranteed to the Portuguese that the existing agreements between Gujarat and Portugal would be observed. pp.121-122, [2]

3) In 1661, the chief merchants of Gujarat negotiated between the English and the Governor of Surat, Mustafa Khan, over a dispute related to a debt. A year later the English, still considering themselves oppressed by Mustafa Khan, threatened to leave Surat altogether. The Gujarati merchants complained bitterly to the Governor, informing him that the English constituted some of their best customers. The Governor backtracked, and asked the merchants to come to some agreement with the English. As a result, the English got considerable concessions, and guarantees of better behaviour, in the future, on the part of the Governor. It is no less important that the guarantees were provided by the merchants, not by the Governor. pp.121-122, [2]

4) In 1649, the Dutch seized two ships belonging to the Emperor Shah Jahan, and held them to ransom, demanding redress to several complaints they had. The Governor employed the Gujarati merchants to negotiate with the Dutch. The Gujarati merchants were worried that if Shah Jahan heard that his ships were seized, he would retaliate, and the merchants would suffer in the ensuing war. Thus, an agreement was quickly reached with the Dutch. pp.121-122, [2]

5) In July 1616, the judge of the Surat customs house allegedly perpetrated some violence on the Chief Banyan. In retaliation, all the merchants closed their shops and left the city after lodging a complaint with the Governor.The Governor brought them back and the judge was dismissed. pp.121-122, [2]

6) During Aurangzeb’s regime (late 1660’s), a particular Qazi was acting towards the Banias in a very tyrannical way, and was likely forcibly converting them to Islam. All the heads of Surat’s Vania families, numbering some eight thousand, deserted Surat. From Broach, they petitioned the emperor Aurangzeb.The tanksell [mint] and custom house of Surat were shut, no money could be procured either for house expenses or trade. Thus, the people of Surat were all stranded. Aurangzeb soon gave a reassuring reply to the merchants which was to the satisfaction of all concerned merchants. pp.121-122, [2].

The family’s referred to in point.6 were led by that of Tulsidas Parekh, an eminent broker to the English. p.239, [15]. In this case, it is worth noting that not only the emperor Aurangzeb, but also the Governor sided with the Baniyas. The Governor said they were free to go where they liked, which outraged the Qazi. pp.121-122, [16]. Strikes and large scale migration were their preferred, and most effective, forms of protest.These examples just reiterate the fact that the Baniyas were extremely powerful, as a group and, many of them, individually, thus demolishing the extortion theory.For Aurangzeb, a devout Muslim, to act against the wishes of the Qazi just goes to show the power they commanded.

References

[1] ``Gazetteer Of The Bombay Presidency’’ Vol.1, Part1, ``History Of Gujarat’’,H.O.Quin

[2] Pearson,``Merchants and rulers in Gujarat’’

[3] Mehta,``Indian Merchants and Entrepreneurs in Historical Perspective’’

[4] MK Gandhi,``My Experiments with Truth’’

[5] Om Prakash ``English Private trade in the western Indian Ocean 1720-1740’’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol.50, No.2/3, Spatial and Temporal Continuities of Merchant Networks in South Asia and the Indian Ocean

[6] Edward A. Alpers,``Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa, c.1500-1800’’,The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 9, No. 1 (1976).

[7]Herald Tambs-Lyche,``Power, Profit & Poetry-Traditional society in Kathiawar Western India’’

[8]Ashraf,``Life and conditions of the people of Hindustan’’

[9] Ranabir Chakravarti ``Nakhudas and Nauvittakas: Ship-Owning Merchants in the West Coast of India (C. AD 1000-1500)’’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol.43,No. 1(2000).

[10] K. A Jacobson,``Routledge Handbook of Contemporary India’’

[11] Sanjay Subrahmanyam,``A Note on the Rise of Surat in the Sixteenth Century’’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol.43, No.1 (2000).

[12] Farhat Hasain ``State and locality in Mughal India’’

[13] R.C Majumdar,``The History and the Culture of the Indian People’’, Vol. 6

[14] Om Prakash,``The Indian Maritime Merchant,1500-1800’’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 47, No.3, Between the Flux and Facts of Indian History: Papers in Honor of Dirk Kolff (2004)

[15] G.A.Nadri, ``The Maritime Merchants of Surat: A Long Term Perspective’’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 50, No. 2/3, Spatial and Temporal Continuities of Merchant Networks in South Asia and the Indian Ocean(2007)

[16] Gokhale,``Surat in the Seventeenth Century’’

[17] A.Truschke,``Culture of Encounters’’

[18]http://www.jainpedia.org/themes/practices/festivals/paryusan/contentpage/1.html

[19]Times of India, Mumbai -10thJuly 2016,``Rs 7 crore bids for Jain monk's last rites’’

[20] M. Whitney Kelting,``Tournaments of Honor: Jain Auctions, Gender, and Reputation’’,History of Religions, Vol.48,No.4 (May 2009),pp.284-308

[21] C.A Kincaid,``The Outlaws of Kathiawar and Other Studies’’

[22] Zaverchand Meghani,``Sorathi Baharvatiya’’

[23] Sir Richard Carnac Temple,``The travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia,1608-1667’’

[24] M.S. Commissariat,``A history of Gujarat’’,Vol 2

[25] M.S. Commissariat,``Studies in the History of Gujarat’’

[26] Lincoln P.Paine,``The Sea and Civilization: A Maritime History of the World’’

[27] Dikgaj, Shanmukh, Saswati Sarkar, Aparna & Kirtivardhan Dave ``Indic intellectual and mercantile collusion with invaders – A relative positioning’’

[28] Surendra Gopal ``Born to Trade’’

[29] Lakshmi Subramanian,``Banias and the British: The Role of Indigenous Credit in the Process of Imperial Expansion in Western India in the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century’’ Modern Asian Studies, Vol.21,No. 3 (1987),pp.473-510

[30] Shivaji & the Surat loot: ‘Modi-fied’ historical facts to woo Marathis? DNA 7th jan2014

[31] William Foster,``The English Factories in India 1661-1664’’

[32] Jadunath Sarkar, ``Shivaji and his Times’’

[33] Saswati Sarkar, Shanmukh, Dikgaj, Kirtivardhan Dave, and Aparna,``Indic Mercantile Collaboration with Abrahamic Invaders’’ https://www.myind.net/Home/viewArticle/indic-mercantile-collaboration-abrahamic-invaders

[34] Saswati Sarkar, Shanmukh, Dikgaj, Kirtivardhan Dave, and Aparna,``Islamic Rulers and Indic Big Merchants – Partnerships and Collusions’’ https://www.myind.net/Home/viewArticle/islamic-rulers-and-indic-big-merchants-partnerships-and-collaborations#.dpuf

[35] Saswati Sarkar, Shanmukh, Dikgaj, Kirtivardhan Dave, and Aparna,``How Muslim Rulers Economically Exploited the Underclass and Appeased the Merchants’’ https://www.myind.net/Home/viewArticle/how-muslim-rulers-economically-exploited-underclass-and-appeased-merchants

[36] Shanmukh, Saswati Sarkar, Dikgaj, Aparna, and Kirtivardhan Dave,``Institutionalized slavery in the Muslim regimes and Indic mercantile complicity’’, https://www.myind.net/Home/viewArticle/institutionalized-slavery-muslim-regimes-and-indic-mercantile-complicity

[37] Saswati Sarkar, Shanmukh, Dikgaj, Kirtivardhan Dave, and Aparna,``Indifference and exemption of Indic merchants to religious persecution of the rest of the populace by Muslim invaders’’ https://www.myind.net/Home/viewArticle/indifference-and-exemption-of-indic-merchants-to-religious-persecution-of-the-rest-of-the-populace-by-muslim-invaders

Comments