Meghalaya’s Quaint Durga Temple at Nartiang

- In Travel

- 10:52 AM, Dec 08, 2023

- Ankita Dutta

The matriarchal family system is prevalent among many communities of the Brahmaputra Valley, besides the Khasis, Garos, and Jaintias of Meghalaya. It is thus a religious custom among several such communities to worship Sakti. A popular belief is that the Khasis and the Jaintias were the original sadhakas of Ma Kamakhya. A significant section of the Jaintias worships this Sakti as Jainteswari Devi in the 600-year old Durga temple situated at Nartiang village of Jowai in the West Jaintia hills of Meghalaya. Another belief is that the present-day Kamakhya Saktipeeth in the Nilachal hills on the south bank of the Brahmaputra in Guwahati, Assam could have been an ancient sacrificial site of the Khasis.

Similar to Kamakhya, there is no murti of the Devi in the Durga temple at Nartiang as well. As mentioned above, the Khasis, Garos, and Jaintias reckon their descent through the female line. The Khasis and the Jaintias believe that the world is ruled by the supreme Goddess called Ka Blai Synshar (Ka meaning ‘She’). Their indigenous religion is known as Ka Niam. With the growing popularity of Christianity in the Khasi society, the suffix Tre, meaning ‘original’, has been added by the non-Christians among them who take pride in themselves as the followers of the Niam faith system. Hence, presently, it is known as Ka Niam-Tre or simply Niam-Tre or Niam-Khasi (meaning ‘original religion’).

The term Jaintia came to be used only after the area came under British rule in the year 1835. This was done to differentiate it from the plains areas of the old Jaintia kingdom, the capital of which was at Jaintiapur situated in the Jaintia Parganas of present-day Bangladesh. A significant section of the Jaintias still resides in different districts of Bangladesh. A popular local belief is that the origins of the word Jaintia may be traced to Jainti Devi or Jaintesvari (believed to be one of the ugra swaroopas of Devi). She was the chief deity worshipped by the Jaintia royal family during the 16th century after consolidating its sway over the plains tracts in the south.

The present-day Jaintia Hills District in Meghalaya constituted the nucleus around which the Jaintia Kingdom grew and prospered. Slowly, this Kingdom began to play an increasingly important role in the politics and culture of the North-East from the 17th century onwards. The Jaintia kings initially ruled in the hill areas only. But, they gradually extended their territory through military conquests both in the areas of the North and the South, but particularly towards the South. Originally, their capital was at Nartiang near the Durga temple although later, they had shifted to the hills of Jaintiapur in the plains of Sylhet (today’s Bangladesh).

Located in the West Jaintia Hills, the Nartiang Durga temple at Jowai, Meghalaya is one among the fifty-two Saktipeeths of Bharat, where Devi is worshipped as Ma Jainti or Jaintesvari. The Devi’s left thigh is believed to have fallen at Nartiang. The present structure of the Durga Nartiang temple was built during the 15th century when a Koch princess Lakshmi Narayan, daughter of Koch Raja Naranarayan, married the Jaintia King Jaso Manik. It is said that the King had a vision of the deity in his dream who had asked him to build a temple there. The reign of Jaso Manik constitutes a glorious chapter in the history of the Jaintia Kingdom of Meghalaya.

Jaso Manik played an important role in the extension of the territories of his Kingdom bordering the Ahom dynasty of the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam to include several smaller Kingdoms, but Gobha, Nellie, Khola, Topakuchi, Baropujia, Sahari, and Phulaguri in particular. These Kingdoms are now a part of the Kamrup and Nagaon districts of Assam. Jaso Manik was also known to have maintained friendly relations with Vijay Manikya, the King of Tripura. The Ahom Swargadeo Pratap Singha, a devout Hindu, also maintained cordial relations with the Jaintia Kingdom, especially Jaso Manik, who undertook many steps for the overall welfare and prosperity of the Khasis, Garos, and the Jaintias alike.

Inside the Durga temple at Nartiang village, Jowai, Meghalaya

Devi Jaintesvari was the presiding deity of the Jaintia royal family and a central figure of the Niam-Tre belief system, the religious rites and rituals of which are quite similar to Hindu Dharma, especially in matters related to birth and death. Just like in any other ordinary Hindu family, the followers of Niam-Tre cremate their dead, unlike the Christians. They also have similar customs for rituals related to marriage and pregnancy. Hindu Jaintias of Meghalaya are primarily concentrated in the towns of Mihmyntdu, Jowai, and Nartiang. A declining religious belief system, Niam-Tre is an ode to Mother Nature’s power to create and sustain life.

The rituals in the Durga temple at Nartiang, a beautiful fusion of Bengali Hindu and ancient Khasi traditions, are not performed in the conventional way as is the case in the plains. The local priest or Syiem (in the Khasi language) is considered the chief patron of this temple. The popular belief here is that the locals of the Jaintia Kingdom were not familiar with the Puja rituals, and since they could not find any Brahmin from neighbouring Assam to preside over these rituals, they decided to invite the Deshmukh Brahmins (known as Deshmukhiyas among the Jaintias) from Ujjain, Maharashtra, and other parts of Western India as pujaris.

Currently, it is the 30th generation of these pujaris who are looking after the day-to-day functioning and upkeep of the temple. Their forefathers were settled in the area encompassing Sylhet in present-day Bangladesh. Jaintia native priests are called Lyngdohs while Jayantia Brahmins are known as Wamons, who are seen as natives because of the matrilineal system that they follow. Bali-pratha is one of the most common and popular modes of Devi worship at the Nartiang Durga temple too. Goats, pigeons, and ducks are the most common animals sacrificed on the day of Maha-Astami during the annual Durga Puja celebrations.

Earlier, the temple used to attract a large number of pilgrims on the occasion of Durga Puja, which is the most important festival celebrated here. But, over the past few years, in the words of Anil Deshmukh, the mukhya pujari of this temple, “There has been a continuous decrease in the number of visitors to this temple.” Just like in any other part of Eastern India, among the Hindus of Meghalaya too, Mahalaya marks the onset of Durga Puja. It heralds the end of the Pitru Paksha period and the advent of Devi Paksha. Besides the Jaintias of Nartiang, the worship of Durga worship is prevalent among the Hindu Khasis of Shella (Sohra/Cherrapunji).

While some among them follow a sattvic diet regime from the onset of Mahalaya, some observe it from the day of Shasti. Khasi practitioners of Niam-Tre pay their obeisance to Hindu deities as well, but, quite interestingly, only very few among them consider themselves Hindu. They rather perceive themselves to be ‘indigenous’. Along with Ma Durga, they also worship Ka Lukhimai, an indigenized variant of Devi Laxmi. On the contrary, however, a significant section of the non-Christian population among the Jaintias takes pride in their Hindu identity. Even today, we can see many Jaintia homes plastered with cow dung, seemingly because of Hindu influence.

During the Durga Puja festivities at Nartiang, the trunk of a banana tree is worshipped as Ma Durga. Decked in fresh marigold flowers and white linen, it is beautifully dressed as Durga in a red saree and decorated with traditional ornaments by the chief Pujari (Syiem) of the temple. The traditional Ka Pastieh Kaiksoo dance of the Jaintias is performed during the annual Durga Puja celebrations. The bhog offered to the Devi is prepared by the local Khasi and Jaintia village women. At the end of the five-day festivities on the day of Visarjan, the banana trunk with all its clothes and jewels is ceremoniously immersed in the nearby Wah Myntang river.

The Jaintias believe that after Visarjan, Devi Durga returns to Her abode in Kailasa which is commonly known among them by the Khasi name of Ki Lum Makashang. Darpan Visarjan is another important ritual that is observed at the Nartiang Durga temple before the actual immersion of the murti of Ma Durga takes place on the day of Visarjan. In this ceremony, the Syiem symbolically immerses the murti (the banana trunk) by capturing its reflection in a bowl of clean water. One has to see the reflection of Ma Durga through this bowl to attain Her blessings. Although this had been the practice traditionally, it is, however, now on the decline.

The worship of Sakti among the Hindus of Meghalaya would remain incomplete without a mention of the sacred groves of Mawphlang village in the East Khasi hills district of the state. People of this region believe that in these forests reside Labasa – a local deity that plays a key role in preserving Bhudevi or Mother Earth. The locals here are of the firm belief that it is Labasa who protects their forests and community from any mishap. Labasa is believed to take on the form of a leopard or tiger and protect the village. The Mawphlang sacred groves have one strict rule – ‘Nothing is allowed to be taken out of here. Not even a leaf, stone, or a dead log’.

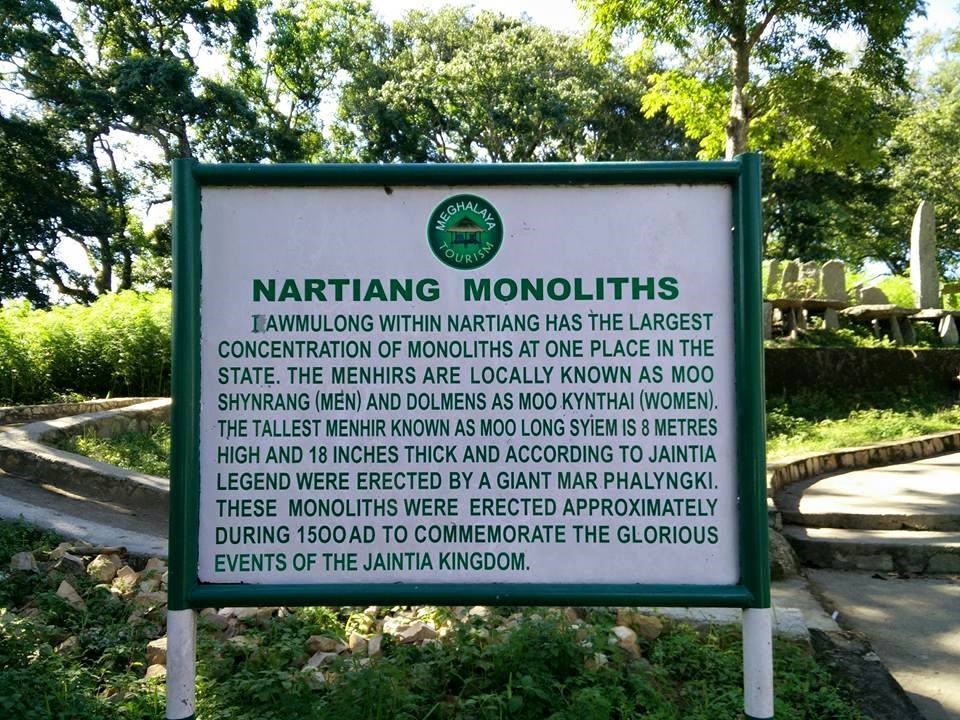

Monoliths at Nartiang village, Meghalaya.

In the Khasi hills of Meghalaya, the sacred groves are known as Lav Kyntang, Lav Niam or Lav Lyngdoh, Khloo Blai in the Jayantia hills, and Asheng Khosi in the Garo hills. Cutting any plant or removing even the tiniest leaf from these forests means disrespect to Labasa who is believed to be the all-round protector of all living beings in the Universe. It is said that whoever attempts to break this rule is punished with a fatal illness or even death in extreme circumstances. Every sacred forest in and around the villages of Nartiang and Jowai in Meghalaya has the presence of an altar, mostly in the form of a monolith, covered on all sides by massive stones that were constructed by the Hindu Jaintia kings to mark their victories.

At the entrance to the monolith garden of Nartiang

(All pictures used in the article are from the author’s own personal collection).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. MyIndMakers is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information on this article. All information is provided on an as-is basis. The information, facts or opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of MyindMakers and it does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Comments