India’s GST: An Analysis of recent Revenue Trends

- In Economics

- 02:58 AM, Dec 10, 2018

- Mukul Asher

India’s large population, 1.32 billion persons in 2016, and its Federal Structure (29 States and seven Union Territories), makes the GST (Goods and Services Tax) reform among the most ambitious globally.

The GST implemented from July 1, 2017, is levied on supply of goods and services under a single tax all across India uniformly. It is thus a dual tax, applied at the Union government level, and in all States and Union Territories.

Appropriate Constitutional Amendments has been made to enable States to levy tax on supply of services in addition to tax on goods, and for the Union Government to levy tax on supply of goods in addition to tax on services. (http://lawmin.nic.in/ld/The%20Constitution%20(One%20Hundred%20and%20First%20Amendment)%20Act,%202016.pdf).

The GST subsumed 17 of the existing central, state, and local taxes on domestic goods and services.

The GST regime has five rates currently: 0 % (mainly on exports), 5%, 12%, 18%, and 28 %. This is comparable to global rate structure, comprising between 3 to five separate rates, plus several items for special treatment, and many exemptions, for comprehensive GST or its equivalent value added tax (VAT) (http://www.oecd.org/tax/consumption-tax-trends-19990979.htm)

There are selected cesses, in addition to GST rates, on some items. The rates have been reduced on many items since July 2017 affecting revenue generation. Most of the revenue is raised from the 12 and 18 percent rates.

The Union government has guaranteed to the States rather generous 14 percent annual increase in the GST revenue over agreed upon base year for five years. The States will have rather long time to adjust to the GST system, and will need to make their medium-term fiscal plans to take into account the period after five years.

The reliance of the States on GST is quite high (between three-fifths and two-thirds of Own Tax Revenue (OTR)). They have much at stake in implementing GST well. The more the GST revenue is generated, the more the States will receive. Thus, the interests of the Union Government and the States are aligned.

The GST Council is an innovative indigenous initiative which has incorporated the spirit behind Cooperative Federalism concept of the current NDA government. The Finance Minister of India, and Finance Ministers of all the States are members. Every single decision so far has been made by consensus not be voting. ()

Another innovative feature of the GST is setting up of an IT backbone to administer the GST. A separate company, called GSTN (GST Network), was set up on March 28, 2013, with the Union government meeting the initial high set up cost (https://www.gstn.org/). Currently, the Union Government and all the states jointly own the GSTN. Such shared IT services have much lower economic costs; make system upgradation more affordable and easier; and

Enable single point filing, reducing compliance costs.

GST not only changes the structure of existing taxes on domestic goods and services, redefine the related taxable events, but has also transformed the manner of levying the tax, e.g. from ‘origin’ to ‘destination’ basis.

Under the ‘origin’ basis arrangements, tax collection is done by the State where the goods and services are produced (or originate); while under the ‘destination’ basis arrangement, tax revenue occurs to the State of consumption of goods and services. Globally, destination basis is the norm. Therefore, India’s GST reform aligns its domestic taxes on goods and services with the global norm.

It has also deepened and refined the manner of collection which utilizes the method of crediting taxes paid on inputs from the output tax, so that only value addition is taxed at each stage.

This manner of collection implies that those entities which are ‘exempt’ i.e. not registered for GST, will still need to pay applicable GST on their inputs, but will not be able to claim these taxes as input tax credit. This implies that for exempt entities, only the value added by such entities is not liable to the GST.

Expected Benefits of GST

At the time of independence in 1947, the leadership of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel led to political unification of India. This was a remarkable achievement, whose importance for India cannot be overemphasized.

But the taxation and other policies pursued after independence prevented India from emerging India as unified national market.

The GST and other complementary reforms, including those related to agriculture, industry, services sector, infrastructure development, and technological initiatives, are rapidly facilitating emergence of unified internal national market. This not only will provide scale of operations necessary to achieve efficiencies, but also significantly reduce transport and logistics costs; facilitating business decisions on the basis commercial logic, rather than sales and excise tax considerations; and bring greater transparency to India’s consumption tax system.

Other goals of the GST are nudging improvements in the accounting standards in both private and public sectors; contributing to greater formalization of the economy; and help improve tax compliance norms in the society.

As an illustration, the Finance Minister of Haryana has reported that the number of assesses under the VAT, Central Excise and Service Tax in Haryana was 0.225 million before the introduction of GST, the corresponding number by mid-2018 was about 0.41 million, an increase of about 80 percent. This base expansion is more equitable and efficient way to generate tax revenue than the alternative of raising effective tax rates.

The Finance Minister reported that the GST collected during 2017-18 (for nine months) averaged INR 15 Billion, which increased to INR 18 Billion during the first three months of 2018-19, implying year-on-year growth of about 20 percent.

Data sources and Their Limitations

The revenue and other data for GST are assembled from the monthly releases of the Public Information Bureau (PIB)

The PIB simply provides data by broad categories of GST revenue, including revenue accruing to the Centre and the States; and number of GST tax filers, without any analysis or trends. Nearly all researchers, including me, have to wade through monthly PIB statements to put the GST revenue trends together.

The web site of GSTN (https://www.gstn.org/) does not provide any revenue data. It does provide other useful numbers, such as total returns filed, (177 million as of November 4, 2018); total invoices uploaded (4.7 Billion as of November 4, 2018), and others. But these are on a dashboard, making detailed analysis difficult.

It is strongly suggested that a more comprehensive GST data, including the revenue derived from each of the GST rates; GST compliance rate (those who have filed in stipulated period) as compared to GST registered (11.7 million as on November 4, 2018, as compared to 6.4 million pre-GST); which is disaggregated by States, and by broad sectors, be provided on the web sites of the GSTN, of the Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs (http://www.cbic.gov.in/), and of the Ministry of Finance ( https://www.finmin.nic.in/).Each State should also provide such disaggregated data on their appropriate state portals.

The GST estimates in the Budget and actual GST revenue by the States should be made available; and compensation given to the States by the Union Government should also be provided on the portal.

The current manner of PIB releases also does not enable estimation of the average effective GST rate. To estimate it, the overall base of the GST would need to be estimated. The overall net GST revenue divided by the GST -base nationally would generate the average effective rate. The effective rate can also be generated in a disaggregated manner estimating revenue derived for each rate compared to the corresponding base, and then taking the weighted average, while accounting for the base of the exempt items.

The effective rates in the above manner also need to be estimated for each state; and by sector, to aid in understanding the GST impact on a disaggregated basis, and in policymaking.

The need for State level disaggregated data is also indicated by noting that under the GST, the compliance rate (i.e. those who have filed returns in stipulated time) of assesses in Haryana had been consistently 5 to 7 per centage points higher than the national average of around 65 percent, a significant improvement over the 55 percent rate in September -October 2017. This rate is expected to improve further.

The above suggests wide variance in compliance rates across the states, and in each state and nationally over-time. Such variances are also likely to be present in other areas, such as revenue from each rate, and sectoral revenue generation. All these variances across states require rigorous, large data based, analysis.

The Union government has entrusted the NITI (National Institution for Transforming India) Aayog to develop the National Data & Analytics Platform (NDAP) in collaboration with private players. The NDAP, which will incorporate Artificial Intelligence (AI), will pool data from Union and State governments for more rigorous policy research, and to aid in decision making. //economictimes.indiatimes.com/articleshow/63651581.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

The NDAP should become part of the efforts at more rigorous, large data -based analysis of the GST revenue, rates, and other aspects.

It is also strongly suggested that each state consider setting up a research institute for public financial management to assist state policy makers and researchers. An important part of its mandate would be research on GST in the concerned state.

GST Revenue Collection Trends

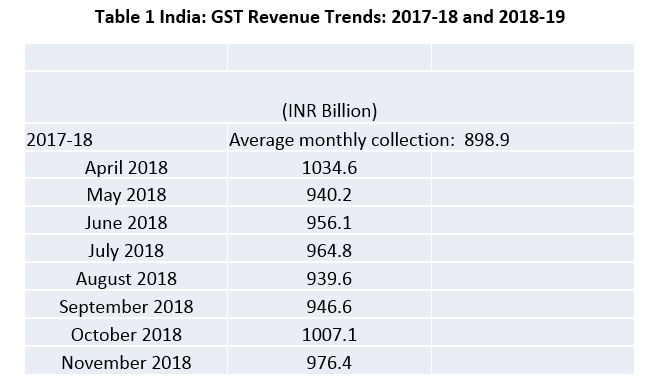

Table 1 provides GST revenue trends for 2017-18 and 2018-19. The data suggest that the average monthly revenue for 2017-18 was INR 898.9 Billion. For the April to November 2018 period was INR 970.8 Billion. This represents an increase of 10.8 percent over the 2017-18 revenue.

Table 1 India: GST Revenue Trends: 2017-18 and 2018-19

Source: Calculated from Press Information Bureau of India Releases (various Dates) (http://pib.nic.in/)

The November 2018 revenue of INR 976.4 Billion was decomposed as followed. Central GST, INR 168.1 Billion, State GST INR 230.7 Billion, and IGST on inter-state transactions, INR 497.3 Billion. The revenue includes INR 241.3 billion on imports; and INR 80.3 Billion in cess revenue, which is to be used for compensation to the states.

After the settlement, including refunds, the Centre received INR 381.7 Billion and States INR 350.7 Billion from GST in November 2018. The Union government has estimated total GST revenue (including from cess) at INR 7439 Billion for 2018-19. This is about one-third of the budgeted tax revenue, and is equivalent to about 4.4 percent of GDP. As a comparison, personal income tax revenue is budgeted at INR 5290 Billion, and company income tax at INR 6210 Billion.

It is difficult to ascertain from the available data how close if the actual GST revenue to meeting the budget target.

Total compensation released to the States in 2017-18 was INR 480.8 Billion; while in April-May 2019 it was INR 39 Billion; and in August September, it was INR 119.2 Billion. (http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=181826) Some flexibility has been introduced in sharing excess of cess collated over compensation amounts to be shared between the Union government and the states.

Concluding remarks

India’s GST has been a landmark reform initiative, with no real parallels globally.

Its relatively smooth implementation in a federal structure, and several indigenous innovations in policy decision making and in administration (e.g. GST Council, GSTN, e-way Bill), and mechanism for continuous improvements easing tax compliance, and rationalizing rate structure0 have not received sufficient deserved recognition, research resources and focus both domestically and globally.

GST has aligned interests of the Union Government and the States. Therefore, both have high stakes in its success.

The publication and ease of availability of revenue and other data on a disaggregated basis, both at the Union government and State Government levels, to all stakeholders, particularly to researchers, and to those with data analytics capabilities, merits urgent attention. Only then, the full aims of the GST can be realized.

Comments