From Swami Vivekananda to Mohan Bhagwat -- What Hindus can take from their Speeches,125 years apart

- In Current Affairs

- 11:51 PM, Sep 12, 2018

- Rajat Mitra

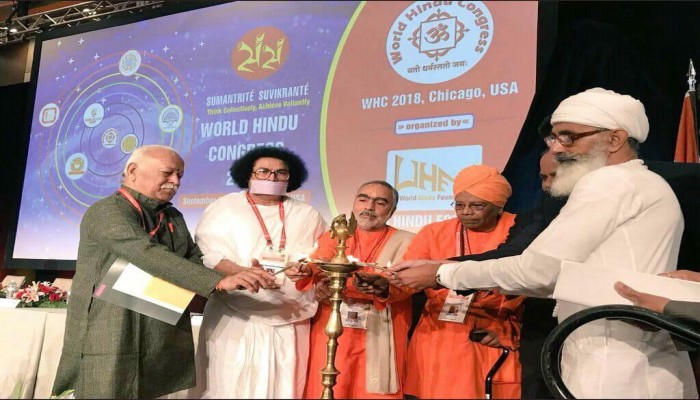

Shri Mohan Bhagwat has stirred a hornet’s nest by comparing Hindus to a lion in his speech at World Hindu Congress held in Chicago. To be fair to him, he did not exactly say that. He only gave an analogy, an example of how a lone lion becomes vulnerable when surrounded by a pack of dogs and can get killed. Nothing unusual in that. Spiritual leaders, motivational speakers do it to arouse their audiences to make them aware of their inner strength.

Swami Vivekananda likened Indians to a sleeping race and asked them to arise and awake and stop not till the goal is reached. He, in my opinion, meant the goal to be a hidden potential of a race that was in chains of slavery. He met with violent protests and some of the comments against him read surprisingly similar to the ones circulating today. His message was not as sharp as the call today.

The former appeal was spiritual to rise from slavery through spiritual salvation while the present one is more of political nature than spiritual for Hindus to rise and be a political entity so that they may come together and never face slavery of a thousand years.

In Vivekananda’s time, no one expected the Hindus to ever rise up and go through a mass awakening and find their rightful place for a long time, such was the pessimism. The prevailing view was that the British empire would never end for a hundred years and Hindu civilization would not be able to survive that. The Hindus were seen by the west as ensconced in a colonial yoke, belonging to an ideology that would annihilate itself as a civilization and be thrown in the dustbin of history.

The two speeches reveal the milestone that the Hindus have journeyed since then. Has someone by likening the Hindus to a lion held a mirror to make them aware of the demise of their political identity throughout history? Was it done because the current thinking is that the Hindu civilization stands at a crossroads? Having broken the colonial yoke 70 years ago and if one may add, almost broken the yoke of a family that suppressed the Hindu heritage of this country, are the Hindus rising in anger facing a moment of déjà vu, a renaissance whose seeds are taking roots.

It wasn’t too long ago when our first Prime Minister, anointed as one who brought us freedom, saw to it that Hindu consciousness dies out and does not take roots. One of the things he did was to call himself “a Hindu by accident”, a statement marked more by perhaps a wish that he was not born into the religion where he wanted to be and dissociating himself. Did it make millions wishing too if being Hindu was something that they should also declare as an accident and not a matter of pride? Is it why many a Hindu never felt pride of being one and is that emerging now? Is it why the rage?

The fear of the “Hindu” rising and connecting to his past glory is perhaps a historical fear that has been suppressed for centuries. Referring to that statement that the Hindu mind is one of the wisest, has it ignited that fear? If one thinks of the Hindu mind as the one that created the Vedic philosophy and mathematics and attaches it to the compassion and universality that made it embrace every form of diversity, will it then become a force for the millennium?

Vivekananda’s speech broke a milestone never done before for the first time. Few people realized its importance then as one which demolished the racial superiority of the whites. Race was a major issue in India in his time, a hundred and twenty five years ago. Feelings about racial inferiority ran deep in Indians, especially Hindus. A barrage of theories were created that showed in cartoons as Hindus being cannibals, write ups that referred to them being uncivilized brutes who prayed to idols and demons. It justified the spread of Christianity on the dark skinned, the heathens. After listening to Vivekananda one scholar in America had remarked, “Listening to him we realize how foolish it is to send missionaries to that country.”

As a child from a Bengali household surrounded by Bengali neighbors, three memories were part of my growing up identity, Rabindra Nath Tagore, Swami Vivekananda and Subhash Chandra Bose. There were pictures of all three of them in different corners of the home and symbolized three very different images. My grandfather would point his finger at Vivekananda and say, “He spoke before a thousand white men and they had to listen silently such was his knowledge. He demolished their arguments about our inferiority. Through his speech he had equalized the white skin with the brown.” To the mind of a young child, it became clear that a man with a dark skin could make an audience of whites listen to his intellect was an achievement that was unparalleled which no Indian had achieved before. As I learnt later, more than anything, what gave Indians the idea that they were intellectually, morally not inferior to the white race in their religion, their philosophy came from listening to that speech. Later the poems of Tagore added on that voice telling Indians to walk alone and realize their destiny by connecting to universality of the human condition with the divine.

Hindus had suffered a fragmentation of their society in their past that hadn’t healed till Vivekananda’s time and till his voice aroused the masses and forever changed the way the Hindu saw himself. The Hindu had become too inward looking at that time making him passive unable to grasp the heritage he had lost. Why and when it happened is lost in the sands of time. One can only imagine that it may have happened over desecrations of temples, over jaziya (tax), over inability to find a voice to record their trauma for posterity. It was to this historical wound that Vivekananda gave a balm, a voice through which he healed his people when he spoke in Chicago.

Speech after speech, he destroyed the superiority of the white race over the dark skinned, the grandiosity they had about themselves about changing the world to their ideology and religion.

Today, a section of Hindus, and their numbers are steadily increasing, realize the historical forces that tried to exterminate their dharma. There is a rising awareness coming from the silence of the world about the extermination of Kashmiri pandits, the way in which they hear they don’t have the first right over the resources in their own country or the term ‘Hindu terror’. All of them are labels that bind one to guilt and the Hindu is not ready that this be thrust on him. Does one find any other term involving “.....terror”, despite children being sexually abused by priests in millions over centuries or terror attacks or conversions being made in the name of another God, I wonder.

Elizabeth Kubler Ross, the psychiatrist who pioneered the concept of different stages of grief in man and the grieving process in humans, often said that even whole societies undergo a process after a loss of its identity similar to individuals in grief. After staying in denial over centuries, when the wheels of time start to change, a rising wave of anger takes over people realizing the persecution they have faced giving it a political identity. Is the Hindu of today heading for that? It refers to an identity that was not allowed to raise its head by the rulers who believed firmly in the superiority of their own religion. Is that why the Hindu speaks the way he is doing? Only the future will be able to tell.

Is there a danger in the rising of the Hindu consciousness of today? In my opinion, as it takes a political identity, it is also coming under attack and will be more so in the days to come. The efforts of those who wanted to destroy it had almost come to a fruition a few years ago with the coinage of the term ‘Hindu Terror’. If the term had been allowed to take roots, would it have crippled the Hindu mind under a layer of guilt from which it would have made it more difficult to emerge for a long time? The idea had infiltrated the powers that were soon to make into a mass narrative that would have crippled and paralyzed the soul of a people. Was it done keeping in mind that an awakening of a people was rising? When the time of an idea comes and a giant is seen to be waking up from slumber, does it not pose a danger by rousing the imagination of the people of why he slept? When the slaves rise, the masters try to silence them.

There was no possibility of a Hindu renaissance in Swami Vivekananda’s time. Survival was the order of the day for the whole society. Yesterday’s survival has given way to a leadership which is not ashamed of proclaiming its roots. The Hindu as a result is not feeling ashamed of his heritage and is connecting with his roots for the first time in his history. The election in 2014 was the first one in which the Hindu society tried to vote forming a political identity, however small. Will it be called India’s first election where Hindus came together as a political identity? Maybe time will tell.

What unity is the recent Hindu forum referring to? Has the spiritual call of Vivekananda now given way to the “political” lifting its head? What will take place if the Hindu doesn’t unite in the present and raise his head? Is the fear rooted in the history of the people? To unite also, one needs to see the link between oneself and his fellow beings spread over a historical period in a shared history. In addition, with a million gods and goddesses, a million different symbols and ways of praying, where will that link come from? Will it come from a shared story of persecution? Of belonging to a tragic fate and annihilation and legacy? Of having faced ones’ institutions, universities and ideologies desecrated? And when that happens, will it lead to a coherent landscape of a people who haven’t felt so before?

The Hindu has produced perhaps one of the finest works of art, science and creativity in human civilization. The philosophy, the music brought out some of the most sublime, the most cathartic literature known to mankind. But with each invasion, with each desecration, it was able to drive that pride deep into the recesses of the society’s consciousness leaving only a shell, a trail of humiliation and outrage that hasn’t died. Is there any other religion which is trying to come to terms with its past as much as the Hindu? That pain of a thousand years as pointed in the speech hasn’t died and lives on. Will it become a transformative force in the lives of a people, sooner than later? Will it become a well spring of a new birth, a renaissance for a civilization once again?

If the Hindu finally comes together believing in a political identity for his people, will that landscape leave a future where our future generations will be safe? The time may have come to answer that.

.

Comments