Firecrackers have been Integral to Dīpāvali Festivities for Eons

- In Religion

- 05:23 PM, Nov 12, 2021

- Bharadwaj Speaks

In this article, I will debunk the myth that bursting firecrackers is a new innovation that was recently introduced into Dīpāvali festivities. It will be shown that bursting firecrackers has always been integral and central part of Dīpāvali.

At the very core of this myth is the presumption that Gunpowder (cf. fireworks) was invented in China in 9th century and brought to India by Muslim rulers. This article debunks this widespread MYTH and throws light on the unknown/hidden history of Dīpāvali and gunpowder. Indeed, so widespread is this myth that gunpowder is popularly known as one of “the "Four Great Inventions of China”. However, this myth starts falling apart when we examine Chinese sources themselves for the origin of Gunpowder.

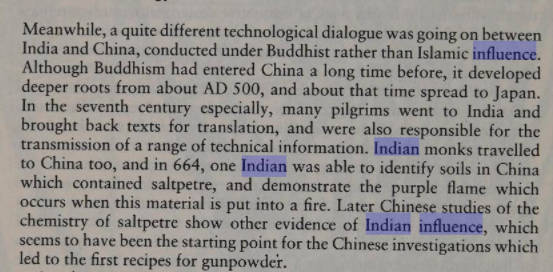

According to Chinese sources themselves, an Indian Buddhist monk who brought gunpowder technology to China In 664 CE, he discovered soils in China containing Saltpetre (primary constituent of gunpowder). Chinese studies of Chemistry of saltpetre show evidence of Indian origin.

Technology in World Civilization, Revised and Expanded Edition, A Thousand-Year History: Arnold Pacey, Francesca Bray · 2021

Of course, this is not to say that Chinese have no contribution to gunpowder technology. They improvised it and made innovations. However, the initial knowledge of gunpowder came to China from India. Even Scholar Roger Pauly, a hardcore Sinophile, admits "Indian inspiration".

Firearms: The Life Story of a Technology - Page 10, Roger Pauly · 2008

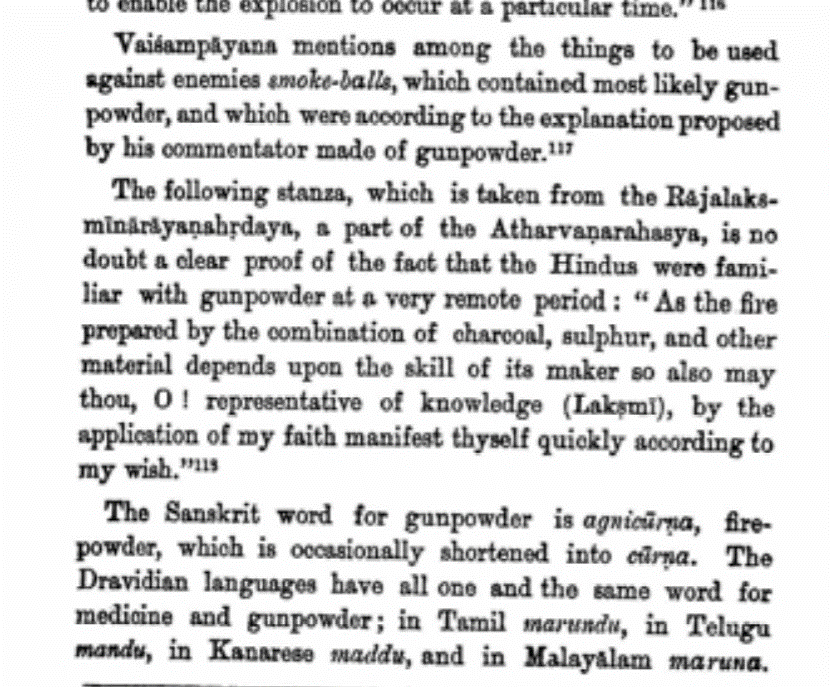

For those familiar with Indian literature, this should hardly come as a surprise. Indian literature contains ample references to what could be seen as an early form of gunpowder. Let us examine these references before jumping into the discussion about Dīpāvali. Vaisampayana, the narrator of Mahabharata, describes the manufacture of smoke balls by ancient Indians using what many scholars see as gunpowder.

According to a medieval commentator of the verse, the aforementioned smoke balls were indeed made of Gunpowder.

Atharvanarahasya mentions the use of charcoal, sulphur and saltpetre to make gunpowder, which are the same ingredients used even today to manufacture gunpowder. In-fact, workers at Sivakasi use these ingredients to make fireworks even today (more below).

A look at how Diwali fireworks are manufactured by traditional makers to this day is very revealing. This video shows traditional maker of fireworks from Andhra in action. It is a simple form of crackers but use of such crackers is very widespread

In the video, the Andhra maker uses basic ingredients to make simple fireworks:

- Suryakara (सूर्यकार, Telugu సురేకారము)- Saltpetre

- Gandhaka (गन्धक, గంధకము)- Sulphur

- Sand

These were known in India since ancient age.

Why would Indians borrow this from anywhere?

The etymology of the ingredients tells us about their origin. The Indian firecracker workers of Andhra and Sivakasi use the Indic Saltpetre (सूर्यकार) whose origin is Sanskritic. They do not use the word Shora (शोरा شورہ) which is Persian for Saltpetre imported in medieval age. It takes an extremely colonized mindset to claim that Indians were incapable of making simple fireworks themselves when they had all basic ingredients since antiquity. Did they have to wait for Muslims to come and teach them to put all these ingredients in a container?

Until this point, we have seen that Indians had knowledge about use of Saltpetre/gunpowder and were perfectly capable of making fireworks themselves. Now we shall come to Dīpāvali.

Why are fireworks used in Dīpāvali? What is the underlying theology? These will be discussed further.

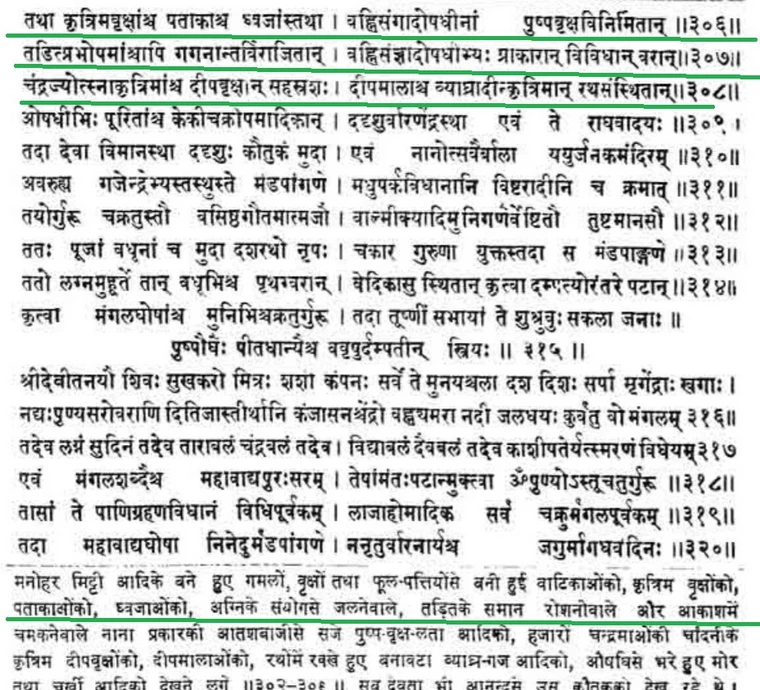

At the core of Dīpāvali is a belief that our departed ancestors would come back on this night. It is believed that on the night of Chaturdashi & Amavasya, the Pitrs would come back. It is the light and noise which shows them the path in the dark. Hence, we illuminate our houses.

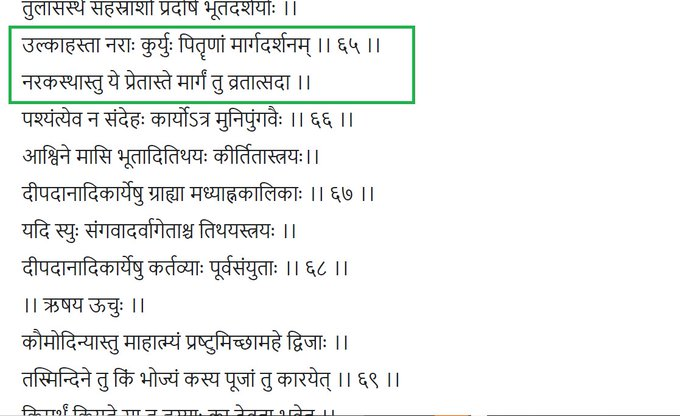

The Skanda Purāṇa is largest of the 18 MahāPurāṇas. It describes the rites to be performed on Dīpāvalī and it mentions this belief. The Vaiṣṇava-khaṇḍa of Skanda Purāṇa says उल्काहस्ता नराः कुर्युः पितॄणां मार्गदर्शनम्। नरकस्थास्तु ये प्रेतास्ते मार्गं तु व्रतात्सदा ।।

The Skanda Purana says Diwali should be celebrated by holding Ulkas in our hands. This will show path to our ancestors. What are "Ulkas"? The meaning of this word has changed with time. GV Tagare translates it as "firebrands". [Firecrackers in their early form were firebrands]

Skanda Purana 2.4.9.65-68

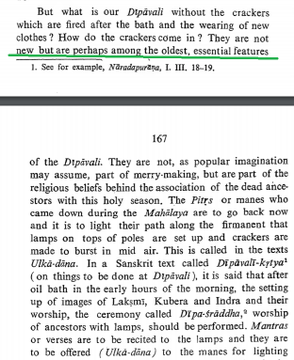

Analyzing such verses, professor of Sanskrit and historian Dr. GV Raghavan concludes that (an early form of) crackers have been a part of Dīpāvali celebrations since earliest times. He says that their religious purpose was to illuminate and resonate the path of departed pitrs.

[Festivals, Sports and Pastimes of India V Raghavan 1979]

In her thesis, Indologist Tracy Pintchman says that the core of Diwali festivity is illuminating the path of deceased ancestors with firecrackers and lights

[Source: Guests at God's Wedding. Celebrating Kartik Among the Women of Benares by Tracy Pintchman · 2005]

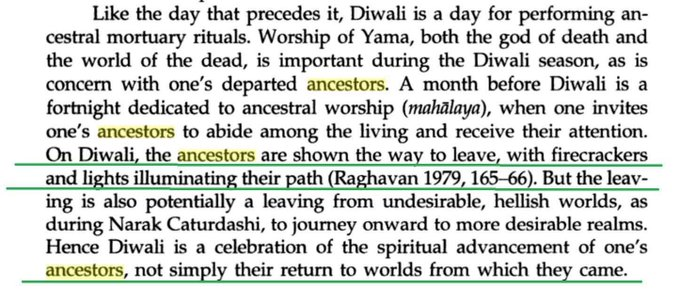

This is also corroborated in Ananda Ramayana. Ananda Ramayana is an epic that has traditionally been attributed to Valmiki. It mentions that fireworks were burst during Lord Rama's homecoming. It mentions crackers which burst and shine in the sky (gaganantarvirajitan).

As against this, it is objected that Ananda Rāmāyaṇa is a work of 15th century. But these dates have been assigned by same Indologists who assigned a date of 500-100 BC (post Buddha) for Valmiki Rāmāyaṇa. Clearly, this is at odds with tradition which puts both in Treta Yuga.

In Hinduism, date doesn't determine validity. What does is acceptance of texts among Sampradayas. Ananda Ramayana easily qualifies such test and is accepted by most Sampradayas.

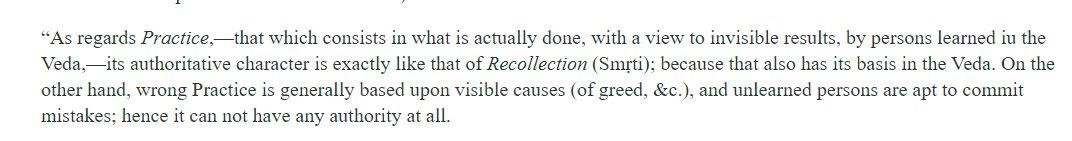

"This practice isn't old enough, ban it" is Abrahamic. This isn’t really how Hindu tradition operates. Such an idea could be seen in Medhātithi's 11th century commentary on Manusmriti 2.6. He says that a practice (in our case bursting firecrackers), what is actually done with a view to invisible results, by persons learned in the Veda has the authority of Smriti.

[Source: Manusmriti with the Commentary of Medhatithi by Ganganatha Jha | 1920]

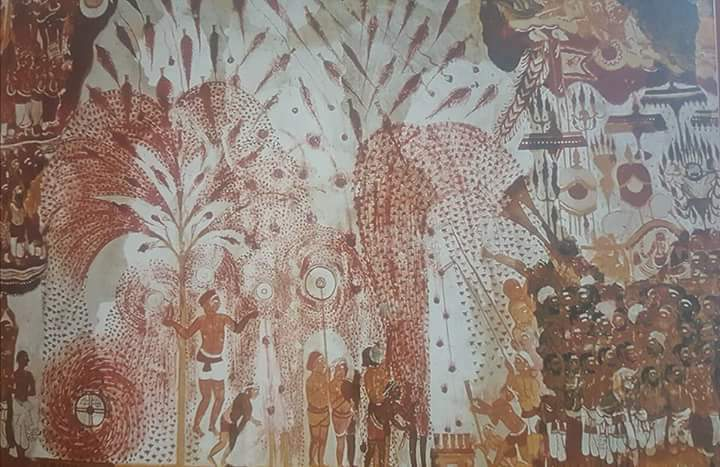

Hard archaeological evidence for all festivals has been allusive in a tropical and frequently (re)populated civilization like India. These are wall murals (of a possibly later date) on 9th century Tyagaraja temple in Tamil Nadu. They depict festival celebrations with firecrackers

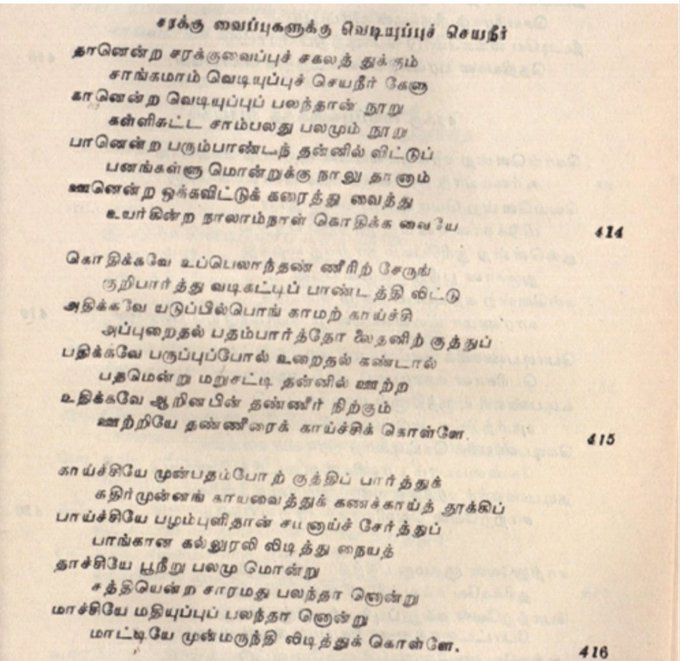

Bogar Sattakandam is a book attributed to Tamil Siddha Saint Bogar. He is traditionally dated to 500 BC, but some modern scholars have put him in 5-7th century CE. Dīpāvali firecrackers are clearly described in this book. It describes the method of preparing the Saltpetre solution (Vediuppu Cheyanir) for all types of Sarakku Vaippu. Fireworks, gunpowder etc. are all described.

Source: Bogar Sattakandam (Sattakandam 415 to 418)

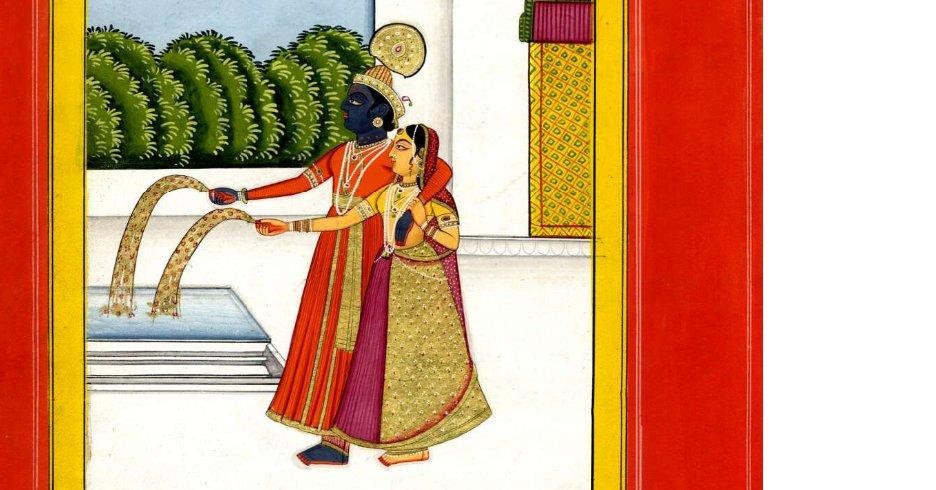

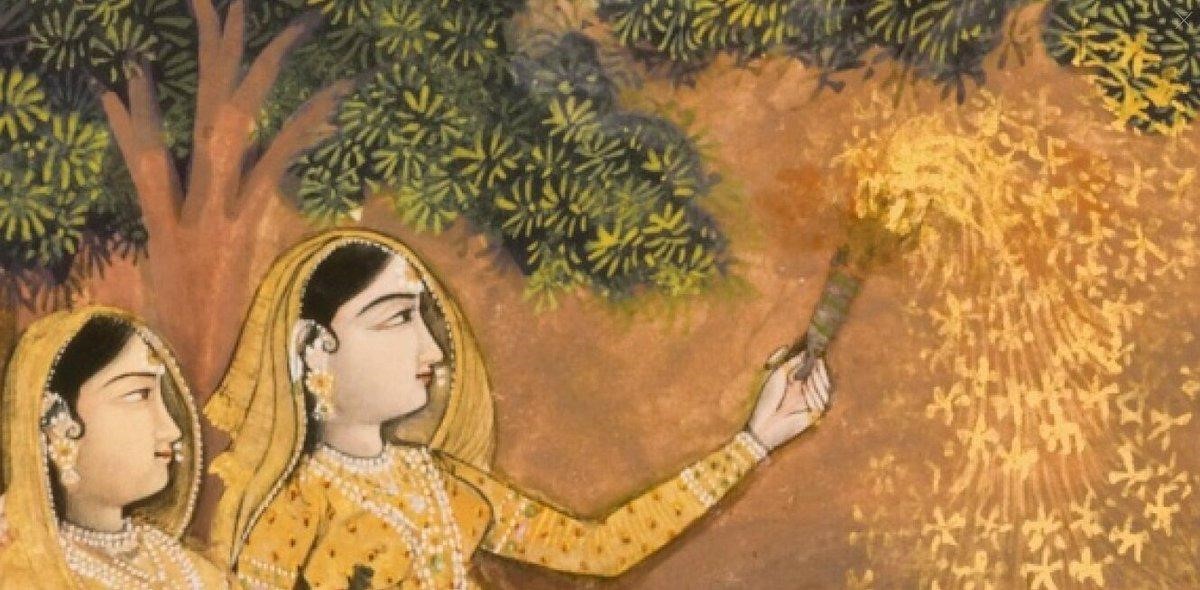

Hindu tradition and Hindu civilizational memory have always remembered firecrackers as an integral part of Hindu tradition. There are thousands of paintings made all over India which show Krishna celebrating Diwali by bursting firecrackers Here is one from Rajasthan school.

Source- https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1940-0713-0-97

An objection is raised that these paintings are late. The earliest available of these Krishna-fireworks series of paintings comes from 16th century. But that is precisely the point. Hindu art and tradition haven’t seen firecrackers as an alien custom that was absent in Krishna's era.

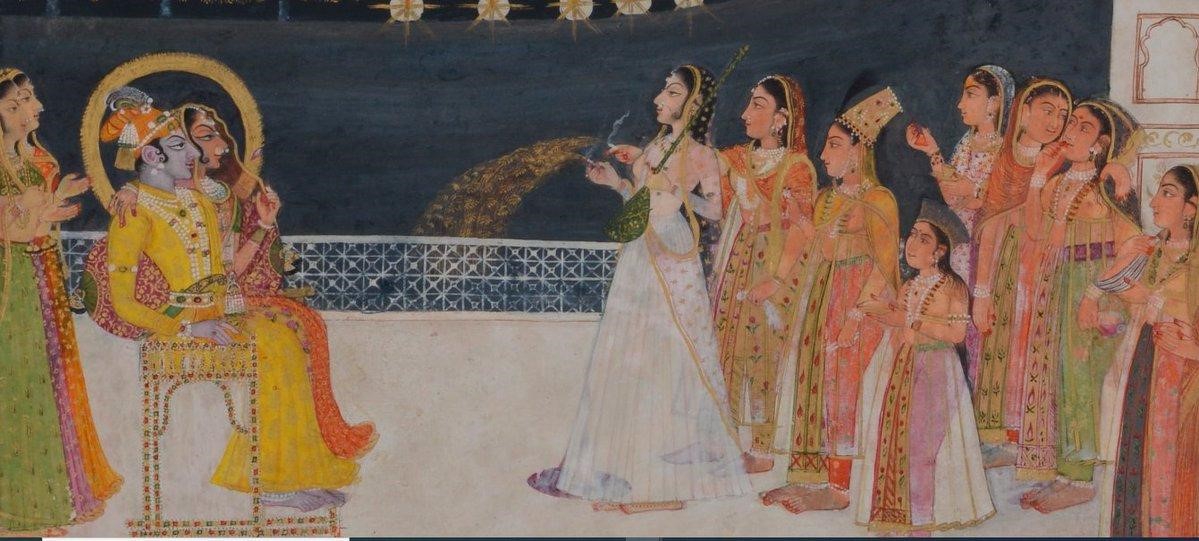

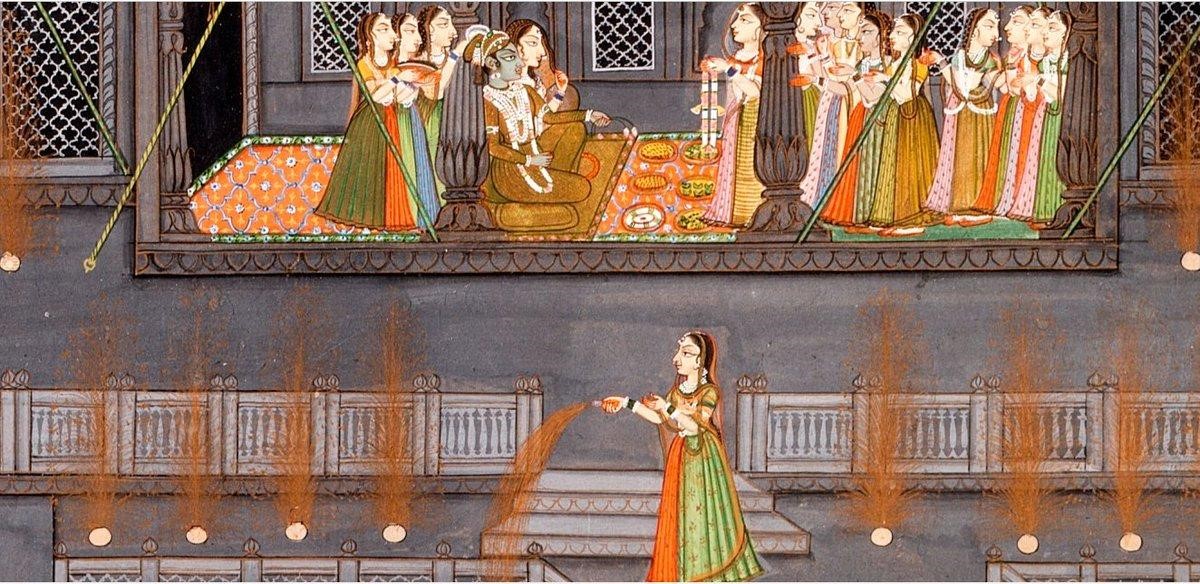

Here is a painting of Krishna watching Dīpāvali fireworks, from Kishangarh (Rajasthan). What do we make of this? Were our ancestors such idiots that they made thousands of paintings depicting Krishna celebrating fireworks which may not have existed during his time? Or was it something else?

Source: https://artsandculture.google.com/story/radha-and-krishna-watching-fireworks-in-the-night-sky/iwUxjNK1OM_ELQ

Source: https://collections.lacma.org/node/198518

Is it possible they remembered these medieval fireworks as a successor of something which had ancient roots in India and in their memory had been integral part of Hindu culture? Hindu civilizational memory DOES NOT see Dīpāvali firecrackers as alien import. Rather, it is the opposite.

As another example of civilizational memory, the great Marathi Saint Eknath (16th cent CE) describes firecracker celebrations in the wedding of Rukmini and Krishna. He describes Agniyantra, Havai, Sumanmala, Chichundari, Bhuinala etc. They can be found even today in Deccan

Source: History of Fireworks in India AD 1400 To 1900 Gode PK

The great Maharashtrian saint and Shivaji Maharaj's Guru, Samarth Ramdas also describes various kinds of fireworks burst by Lord Rama's army in his Ramayana. These firecrackers include havaiya, nala, phula (phuljhari), ghosha etc.

Source: History of Fireworks in India AD 1400 To 1900 Gode PK

Let us pause and ask ourselves. What do we make of this? If we assume firecrackers were imported in Muslim age, the inevitable conclusion is that all great Hindu painters, poets and scholars were collectively wrong and deluding themselves when they mentioned fireworks in ancient India.

But there is another, more plausible possibility which does not require denying every evidence. Skanda Purana says Dīpāvali should be celebrated by holding Ulkas in our hands. These ulkas were mostly likely firebrands which served two purposes:

1) Made noise 2) Illuminated the sky.

Dīpāvali celebration with firebrands was its earliest form and must date back to thousands of years. Even today, such Dīpāvali firebrands can be found. Take Kaunriya Kathi of Odisha. It is a basic Dīpāvali firebrand without gunpowder. But it illuminates and makes noise.

Such firebrands illuminated sky which could explain why some commentators described उल्काहस्ता of Skanda Purana as दीप. This was older, original form. Traces of it can be found in some medieval paintings. This painting from Mir Kalan school depicts what is close to older form.

Source: https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/2014/art-imperial-india-l14502.html

At one point (definitely before the Muslim age), Saltpetre was incorporated into firebrands. While use of such crackers gradually became widespread, more conservative ones persisted with the older form of firebrands which explains why not many ancient texts describe this innovation. Crackers used in Ancient India were different from today's modern crackers.

Just like chairs used in ancient India were different from today's modern chairs. Does that mean chairs are not a part of Indian history? Almost everything used today is different from its predecessors. If one goes by this logic, one could as well conclude that Ancient India had NOTHING in our culture because everything today is different from its yesteryear's predecessors. What is relevant is that the concept existed. And the concept was quite simple.

The concept was to use a combustible substance on the night of Dīpāvali to make a lot of noise, illuminate the sky and show the path to our departed ancestors. This is mentioned in the Skanda Purana itself and is true irrespective of whether Ulka means modern firecrackers.

What does it all show? With advancement of technology, everything changes. But the basic concept of using combustibles to make noise and illuminate the sky on the day of Dīpāvali existed since ancient times. This was not a foreign import or medieval 16th century concept.

All the images are provided by the author.

Comments