Burma Through the Ages: Its Bittersweet Relationship with India

- In History & Culture

- 03:55 PM, Jun 13, 2023

- Biman Das

The neighbouring nation of Myanmar evokes a moment of awkward silence among Indians today when its name drops into the conversation. For all intents and purposes, it has been castigated as a pariah state, branded as a bloodthirsty nation that is a blot on humanity by the global media. Naturally, it comes as no surprise that some Indians have conceived negative notions about this neighbour of theirs. But looking back into history, citizens of both nations would discover that there was a mutual sense of acceptability among the Burmese to be called Indians at one point.

The historical links between Myanmar and India can be traced back at least to the 4th century A.D. during the heydays of the Dhanyawadi kingdom in today’s Rakhine state. Local folklore believes that the kingdom dated back even earlier with Gautama Buddha himself having visited the area during his lifetime. Apart from the Dhanyawadi kingdom, the region also had a strong presence of Bengali Hindu-Buddhist dynasties such as the Chandra dynasty and the Deva dynasty. The influential Bengali population of the region would decline with the migration of Burmese from the Irrawaddy valley and subsequently get absorbed into the incoming wave of Bamar immigrants giving way to the modern Rakhine populace.

The history of Arakan itself is considerably different from that of the Irrawaddy Valley as this region was a stronghold of Mahayana Buddhism rather than the Theravada tradition. It is not unsurprising to find this out as the Mahayana and Vajrayana schools held great sway in Bengal at the time. A specific form of Tantric Buddhism called Ari Buddhism, a cross of Hinduism, Buddhism and nats (folk deities, some being of Indian origin) was the primary faith in the Burmese Pagan kingdom until the conversion of King Anawrahta at the hands of Mon priest Shin Arahan. Under the influence of said priest, the king had all the pratimas of the deities put into the Nat-hlaung kyaung temple (lit “monastery where the nats are imprisoned”), which was originally dedicated to Maha Vishnu and his dashavataras (ten great incarnations). Ironically, the Kanjeevaram school of Theravada Buddhism that Shin Arahan had attempted to spread would eventually get supplanted by the Mahavira school due to the influence of another Mon monk named Shin Uttarajiva.

Despite attempts to purge Hindu elements from by the purists, nats have amalgamated deeply into Burmese culture today, so much so that deities such Thurathadi (Saraswati), Thagyamin (Indra), Withano (Vishnu) and Paramizwa (Mahadeva) are seen to be of native origin. The Burmese adaption of the Hindu epic Ramayana, penned by Rishi Valmiki came to be known as the Yama Zatdaw alongside lesser adaptations such as the Mon “Loik Samoing Rama”. Some contemporary renditions of the tale include Rama Thagyin by U Aung Pyo (1775), Rama Yagan by U Toe (left incomplete in 1784 because of the author’s death), the Rakhine Alaung Rama Thagyin by Hsaya Htun and the seventeenth century Rama Wutthu (whose original manuscripts have now been lost).

A peculiar characteristic seen in many of these adaptations is the localisation of the Indian story; Ravana is called Dattagiri, Kumbhakarna becomes Gombiganna and Surpanakha becomes Mi-gambi or Trigatha (meaning three-headed). Likewise, the Dronagiri mountain (also called Gandhamadhana) that bore the sanjeevani (Hse Myit in Burmese) has been substituted for Mt. Popa and the origin of Inbaung lake, Yamethin district has been attributed to Hanuman stumbling and falling to the ground during his journey.

The Northeast Indian regions of Assam and Manipur were particularly vulnerable to the Burmese kingdoms that sought to capture these regions. Sensing an opportunity following the vacuum left by the Moamoria rebellion under the Ahom rule, Burmese king Bagyidaw took the Ahom throne in 1817. The marauding armies of the Konbaung kingdom laid great waste to Assam taking away many slaves to Myanmar while others were killed and many women raped by the soldiers from Ava. The devastation from the Burmese invasions following the Moamoria revolt ended up severely depopulating Assam (which would later be used by the British as a ruse for the mass importation of Bengali Muslims) and thus came to be known as Manor Din (Days of Burmese Terror).

The neighbouring kingdom of Manipur did not fare much better with a third being taken away into captivity and another third having fled to Western territories such as Barak valley, Sylhet and Tripura. The period of occupation called “Chahi Taret Khuntakpa” (seven years of devastation) also saw the Bishnupriya Manipuris, another indigenous Hindu community to Manipur being virtually wiped out from their homeland.

The Konbanung rule was considered to be so brutal that even the Rakhine people who were nearly identical to them in culture had to flee in large numbers when the Rakhine kingdom of Mrauk-U fell to Bodawpaya. Mass deportation of ethnic Rakhines to the Irrawaddy valley also had a similar demographic effect on Arakan creating a vacuum that would be filled by Muslim migrants that arrived in large numbers from Chittagong over the next few decades.

The Konabung kingdom would then go on to lose its territorial gains in three successive wars to the British (1826, 1853 and 1885) after Bagyidaw’s failed attempt to capture the lucrative Bengal region in 1824. While Assam, Manipur, Arakan and the Mon ruled Tanintharyi were taken in the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826, Lower Burma would be ceded in 1858 and thereafter, the rest of Burma in addition to the exile of the royal family in 1885.

British Burma would then be directly administered by the British as another province of British India. However, they soon began to worry about the possible consequences of their actions. Burma being integrated into India would essentially give Delhi a direct passage into the heartland of Southeast Asia. Furthermore, Burma would also soon catch the flames of anti-colonial nationalism emanating from Bengal, making their suspicions all the more worrisome.

To counter the consolidation of an eventual revolt against the English monarch, the 1932 Burmese general election was run on the controversial topic of separation from British India. Much to the astonishment of the colonial administration however, the Anti-Separatist League led by the Mawmyintbye Party emerged victorious winning 42 of the 80 seats, much ahead of the Separatist Block’s mere 29. Humiliated by the defeat of the separatists whom the British were rooting for, they attempted to bribe the Anti-Separatist coalition’s leader Ba Maw by offering him the post of the first Burma Premier (nominal head). This would be followed by the colonial administration in London passing the “Government of India Act, 1935” to effectively amputate Myanmar from India in 1937.

The colonial government, despite carving out Burma, preferred to import a large number of Indians (largely from Bengal and Madras provinces) to the region for administrative and economic reasons. The immigration would be so intense that Indians made up 7% of the entire population of Burma by 1931 with Rangoon, the provincial capital having an Indian majority. These Indians would then have to face the brunt of the Japanese occupation, many having been forcibly made to construct the Siam-Burma Railway. This would force over five lakh Indians to flee to Assam on foot. Another wave of xenophobic oppression against Indians would occur when the ethnically Han Chinese dictator Ne Win usurped power in the state and stripped many Indians of their citizenship. This would force another three lakh Indians to emigrate, some of whom settled in Moreh creating the present Manipuri Tamil diaspora.

Whether the Burmese choose to join the Indian Union again in the future is up to the inhabitants of Myanmar to decide. However, historical instances will continue to talk about the dark period when the British chose to separate people against their wishes and ironically may foresee the same in their homeland in the aftermath of Brexit’s pandemonium.

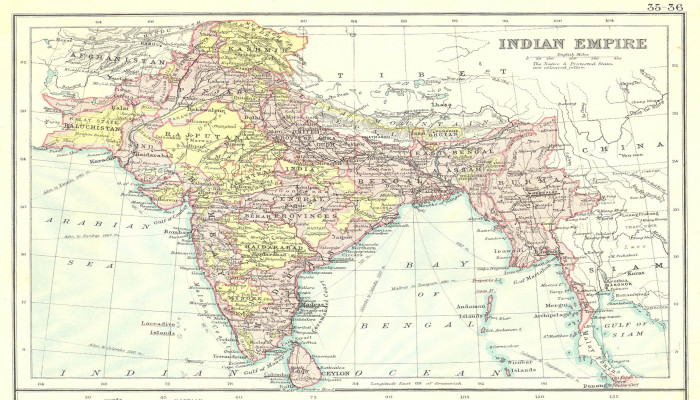

The cover image is Map of British India, 1912 by John Bartholomew provided by the author.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. MyIndMakers is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information on this article. All information is provided on an as-is basis. The information, facts or opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of MyindMakers and it does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Comments