Assam’s Struggle to Reclaim Lost Lands

- In Current Affairs

- 12:43 PM, Aug 06, 2025

- Ankita Dutta

The continuous eviction drives undertaken by the Government of Assam against illegal Bangladeshi immigrants settled in different places of the state, have drawn the attention of both the national and international media. Large-scale encroachment upon Government, Reserve Forests and other Protected lands was extensively documented during the State Government Survey conducted in 2021. Therefore, the recent eviction drives in the districts of Dhubri, Nalbari, Goalpara, Lakhimpur, and Golaghat were not only necessary, but they also underscore the need for many more such actions by the Government to recover illegally occupied public land.

It is not only in the larger interest of freeing the local people’s lands and Government lands from the occupation of illegal Bangladeshis, but also for the protection of biodiversity. If we observe closely, a definite pattern emerges, making it clear that the specific locations where massive eviction drives have been carried out in the past two months are areas of immense environmental, social, and cultural significance in Assam. Based on our field studies, this article presents a case study of four such different locations –

Hahila/Hasila Beel, Goalpara:

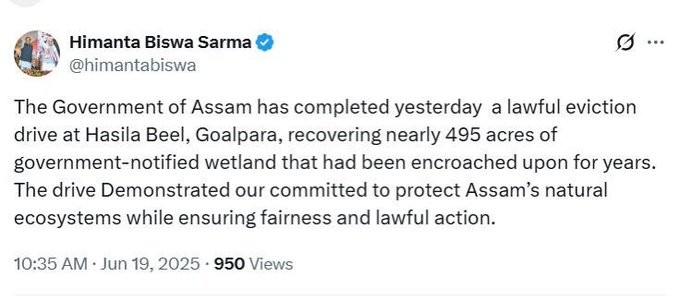

On the early morning of June 16, a large-scale eviction operation was carried out at Hahila Beel, a well-known wetland in Assam’s Goalpara district, which is even larger than the ecologically important Deepor Beel near Guwahati. The eviction, supported by heavy security, was carried out as per legal procedures. Three eviction notices had been issued to the occupants prior to the operation – one each in 2023, 2024, and most recently on June 14. Public announcements were also made via banners and loudspeakers, asking them to vacate the land by June 15. The administration stated that around 20-25 families vacated voluntarily after the latest notice. The operation aimed to clear illegal encroachments on nearly 1,500 bighas of Government land, including households, five Lower Primary schools, and a Jal Jeevan Mission Project.

It may be noted here that due to variations in local pronunciation and transliteration into English, the name ‘Hahila Beel’ has been mistakenly recorded and officially recognised as Hasila Beel. In reality, as preserved in local oral traditions, folklore and memory, the correct name of this famous wetland is Hahila Beel. The misnaming is a result of administrative oversight and the gradual erosion of oral traditions, language and heritage from all official revenue and administrative records. The name ‘Hahila’, it is believed, has been derived from the Assamese word haah, meaning swan flocks, which once used to glide gracefully across the pristine waters of this wetland.

Before it was encroached upon and degraded, the area was a virgin wetland landscape – serene, sacred, and full of natural beauty and wonder. It was mostly used by the local fishing community of the Kaibarttas for their livelihood. Swans were the main attraction, and children would often go to watch them at sunset, their white feathers glowing against the golden light. Those days were not mere fun times; they were lived experiences that shaped the collective memory and identity of generations after generations.

https://x.com/TheNewIndian_in/status/1935597387814195315

For the Hindus of Goalpara, Hahila Beel is not just about natural beauty – it was, and still is, a place steeped in deep spiritual energy. A popular local belief prevalent in the region is that a massive iron chain is submerged somewhere in the waters of the wetland, and no one has ever been able to pull it out. The story, passed down through generations, remains one of its many unresolved riddles.

Earlier, it was a common custom among the Rabhas and Koch-Rajbongshis to offer prayers here, lighting earthen clay lamps, and seeking divine blessings, especially during difficult times and particularly for utensils needed in wedding ceremonies. In what many even today describe as “miraculous”, the requested items would mysteriously appear near the wetland by the next morning. Hindus’ belief in the power of Hahila Beel. For them, it was a place of silent blessings. It inspired a feeling of quiet sanctity in the hearts and minds of anyone who visited it.

However, over the decades, encroachment, neglect, and the fading of oral traditions transformed this once-sacred landscape into a degraded patch of land, stripped of its ecological richness and cultural sanctity. Swans are no longer found in their waters. Its majestic silence has been replaced by the construction sounds. Today’s young generation is not aware of Hahila Beel’s significance in the socio-cultural landscape of Assam. The Government of Assam’s recent eviction drive at Hahila Beel is an attempt to not only clear the area of illegal encroachments but also revive its once-pristine waters and restore the traditional fishing sector of Assam to the hands of the Kaibarttas.

In this regard, the State Cabinet has also decided to notify Goalpara’s Hahila Beel as a Proposed Reserve Forest (PRF), along with two other wetlands – Urpod Beel and Kumri Beel – both in Goalpara. Located at Agia village at a distance of 9-km from Goalpara town, Urpod Beel, designated as a conservation reserve/wildlife sanctuary by the Assam Forest Department, is one of the biggest natural lakes of Lower Assam. It is home to many varieties of fishes and a hotspot of thousands of annual migratory birds. It has been recognised by the Bombay Natural History Society as an Important Bird Area. Urpod Beel is also known for aquatic plants such as water lily and common water hyacinth. However, its area is dwindling over the years due to indiscriminate human encroachments, deforestation, and the establishment of brick industry.

The Kumri Beel, on the other hand, is located near the Southern bank of the Brahmaputra. The ancient Paglartek Shiva Temple situated nearby in Borbhita village adds to the cultural significance of the region. Covering an area of about 200 hectares and surrounded by lush green forests and marshy lands, the Kumri Beel was earlier surrounded by several villages of people from the Kaibartta fishing community. However, rampant encroachments by Bangladeshi Muslims over the years compelled the Kaibarttas to migrate elsewhere.

In a welcome initiative, the State Tourism Department of the Government of Assam has been directed to prepare a master plan to develop tourism prospects around these ecologically important areas. They have immense tourism potential for birdwatching, especially during the winter season, when numerous migratory birds visit the area.

Rakshyasini Pahar, Goalpara:

Chief Minister Dr. Himanta Biswa Sarma mentioned that after Hahila Beel, a second phase of the eviction drive in Goalpara is being planned at Rakhyasini Pahar in the Matia Sub-Division of the district. A historically significant area, Rakshyasini Pahar is located approximately 6.3 kilometres from Goalpara town near the Goalpara Forest Gate along the Krishnai-Garo Bajar and Sri Surya Pahar Road bordering the river Jinari.

Encompassing around 2,700 hectares of land, Rakshyasini Pahar, an ecologically sensitive zone, was declared a Proposed Reserve Forest (PRF) in 1959. Though detailed records are limited, the region was known for its lush greenery and medicinal plants till at least the early 1990s. Dense forests of sal and segun trees were found in abundance in this region back then, when the area remained largely untouched by human habitations, except for a few tea stalls owned by the local Hindu villagers of the area. The shifting demographics in Goalpara have been primarily due to internal migration of people driven by socio-economic factors, leading to pressure on land and resources. This has exacerbated encroachments and caused a demographic imbalance in many areas of the district.

Since 1997, Bangladeshi Muslim families from the flood-prone char areas of Barpeta and Goalpara districts began migrating to Rakshyasini Pahar. This sparked the beginning of an influx of Bangladeshi settlers throughout the late 1990s and the early 2000s. The devastating floods of 2024 that hit Bolbolla-Sildubi region in Goalpara district displaced many local residents. The resultant vacuum had spurred the migration of Muslims in large numbers from the flood-prone areas of Barpeta and Bongaigaon districts.

Unlike the previous residents of Bolbolla, many migrants who have now settled in the entire Rakshyasini Pahar forested area with political support, encroached on lands and engaged in illegal logging and quarrying, causing massive deforestation. Over time, these temporary migrants who had initially arrived here seeking shelter became permanent residents. Reportedly, several MLAs of the Congress Party at that time encouraged illegal immigration of Bangladeshi Muslims and encroachment on forests and tribal lands purely for electoral advantage.

Based on our studies conducted on the subject in different parts of Assam, we have often observed that the people who encroach upon Government lands often claim that they are erosion-affected or their farmlands were destroyed due to siltation after the annual floods. But the state administration never checked their details, let alone cross-checked them with the Revenue Officials of the respective places from where they initially came. This was normally not done, as not many people were ready to take such pains to go through the rigorous bureaucratic process. It is precisely because of this reason that over the years, even persons who have land elsewhere, say in Dhubri or Goalpara district, managed to illegally grab Government land somewhere else, say in Golaghat or Jorhat, claiming themselves to be landless.

Years and years of political appeasement of Muslims and neglect of our natural resources allowed illegal settlements to expand in places like Rashyasini Pahar of Goalpara. Around 2010, Rakshyasini Pahar experienced another huge influx of people due to the increasing popularity of a self-proclaimed godman named Bosta Baba, who attracted thousands of poor Muslims to his fold in the name of water-healing therapies and remedies for curing different diseases. Following the death of Bosta Baba around 2016-2017, some of his followers from the char areas of Barpeta began migrating to Rakshyasini Pahar on religious grounds, completely transforming the region’s demography.

Many masjids were built on illegally encroached lands, and conflicts between Hindus and Muslims became quite frequent. Temples were destroyed by miscreants and local Hindus were even killed if they dared to protest. Encroachments also affected hamlets like Duba Para and Pahar Singh Para in the Jinari and Surya Pahar River basin areas.

With the State Government’s renewed efforts to reclaim Rakshyasini Pahar and its adjoining areas from years of illegal encroachment, attention has now turned to the long-lost and nearly-forgotten Mama-Bhagin Ashram. Located about 7 kilometres from Goalpara town, the Ashram lies around two sacred stones that have served as the main centre of worship for local communities such as Rabha, Garo, Nepali, Santhal, Rajbongshi, Sutradhar, and Nath. This Ashram was once a vibrant religious, cultural, and spiritual centre of Lower Assam. However, it has faded into obscurity over the years due to continuous neglect, dwindling visitors, and encroachment. In 1980, the Ashram was allotted eight bighas, four kathas, and five lechas of land by the administration. However, the current area of the Ashram is only one bigha. It is now visited by devotees only during Maha Shivaratri or when any fair is organised.

The Government’s recent drive to identify and demarcate forest land in Goalpara, besides the preservation of heritage sites within Rakshyasini Pahar, has inadvertently revived interest in lesser-known Hindu religious places such as Mama-Bhagin Ashram. Locals hope that alongside ecological restoration, steps would be taken to officially recognise and restore the Ashram’s rich cultural and spiritual legacy. Besides, land ownership laws should be strictly enforced, land surveys updated, and legal accountability ensured for protecting Government and community lands. Otherwise, there could be long-term, irreparable consequences for the region’s socio-cultural fabric, environmental sustainability, and law and order.

Paikan Reserve Forest, Goalpara:

On July 12, another major eviction drive was carried out by the Goalpara district administration and the Forest Department in the Paikan Reserve Forest under Krishnai Range adjoining Meghalaya’s Garo hills. The goal was to reclaim 1,032 bighas (140 hectares) of encroached forest land in line with ongoing efforts to restore biodiversity in protected ecological zones, besides reclaiming critical wildlife habitats that have been degraded due to illegal settlements.

Ahead of the eviction, almost 70% of residents voluntarily vacated their homes after receiving prior notices. Almost 1,080 families were evicted from heavily settled key areas like Ashudubi, Bidyapara, and Betbari. They have been residing in these places without legal authorisation for several years. Although the illegal settlements were not officially recognised as revenue villages, authorities had earlier permitted the establishment of schools, electricity lines, an Anganwadi centre, and a Jal Jeevan Mission water supply scheme in the area. Eight mosques were also built illegally, but, most of them were demolished during the eviction.

Established in 1982, the Paikan Reserve Forest encompasses about 710 hectares of land. It had been encroached upon by people of Bangladeshi origin over the past 25 years. The settlers came mostly from the flood-affected riverine char areas of districts like South Salmara-Mankachar and Barpeta. However, they were originally from East Pakistan. After settling down at Paikan, they have lived there for generations. The recent eviction was made possible through the legal framework of the Assam Forest Regulation, 1891, which allows forest authorities to remove unauthorised occupants from Reserve and Protected Forest areas. It was in response to a suo motu PIL by the Gauhati High Court, urging swift action against forest encroachments.

The eviction drive at Paikan is particularly significant as Goalpara records some of the highest rates of human-elephant conflict in India. Unabated encroachment and unauthorised plantations within the Reserve Forest have contributed to these issues. It would not be an exaggeration to say that almost every month, one or the other incident of human-animal conflict is reported from Goalpara.

During the peak season, groups of 70-100 elephants each move from one forest to another, from Goalpara to Meghalaya, often giving rise to conflicts. Thus, by restoring the forested landscape, authorities aim to reduce confrontations between local communities and elephants, which have intensified due to habitat fragmentation in recent years. The eviction is also a part of a broader conservation strategy aimed at ensuring safe corridors for wildlife movement while, at the same time, reasserting legal protection over Reserve Forest lands and improving coexistence between humans and wildlife. It is not only a grim reminder of the urgency surrounding environmental conservation but also a stark warning bell of the dangers of encroachment.

Uriamghat, Golaghat:

In the last week of July,2025, the Government of Assam launched the biggest-ever multi-phase eviction drive to reclaim over 3,600 acres of forest land in the Rengma Reserve Forest located at Uriamghat, along the Assam-Nagaland border in Golaghat district. Over 5,000 bighas of forest land were reported to have been illegally occupied in the Uriamghat and Negheribil areas by Muslim families from Dhing and Lahorighat in Nagaon and Morigaon districts, respectively. The Rengma Reserve Forest, which has seen widespread encroachment in recent decades, is not just an ecological asset of Assam, but it holds profound ancestral, historical, and cultural importance for the Rengma Nagas, one of the oldest indigenous communities of the region. Despite massive religious demographic change in Nagaland, a significant section of the Rengma Nagas residing in Assam are ardent adherents of the traditional Naga religion even today. Many among them are devotees of Mahapurush Srimanta Sakardeva, too.

The land encompassing the Rengma Reserve Forest forms a part of the traditional/undivided Rengma Naga homeland, predating modern administrative boundaries and political developments. Besides the Rengma Reserve Forest, it includes areas such as the Rengma river valley, Rengma tea estate, Gholapani, Halodhibari, Lisa Gaon, Rengma Pathar, Uriamghat, Sarupathar, Naojan, and Naokhuti under Golaghat district; Nambor Reserve Forest, Kaliani Reserve Forest, Dhansiri Reserve Forest, Doldali Reserve Forest, Diphu river valley, Jamuna River valley, and Deopani under Karbi Anglong district; and, parts of Nagaland including Tseminyu district. Among all these, Uriamghat’s Rengma Reserve Forest is a living heritage site for the Rengma people, deeply embedded in their identity and cultural continuity.

However, large-scale supari (betel-nut) cultivation has been taking place on this sacred land – allegedly one of the largest such plantations in Assam – by mixing betel-nut imports from neighbouring Myanmar with local produce. This has had the effect of disrupting wildlife corridors, besides contributing to habitat loss for endangered species, including the Bengal tiger. The encroachments at Rengma Reserve Forest in Uriamghat have persisted for more than ten years, raising concerns over land mafia, land rights of the indigenous people, illegal supari trade, and environmental degradation.

A common strategy adopted by Bangladeshi Muslims in many areas of Assam, including Uriamghat, is to first capture the lands of local Hindus through the land mafia and then bring more people of their community from different places to settle there. After that, they started illegal mining in that land, thereby adversely affecting the natural environment.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8rLCpRIy7VE

As per locals of Uriamghat, it was in December 2010 that many Bangladeshi Muslim families settled in the area. They had even destroyed various valuable properties of the locals. For a long time, Nepali Hindu residents of neighbouring Pithaghat, Kherbari, Dayalpur, Lakhinagar, Halodhibari, Silonijan, Pujabil, and Sonaribil villages in Sarupathar Sub-Division of Golaghat district have been raising complaints of a huge number of non-residents, unknown people casting votes as villagers of the area in many Lok Sabha and Assembly elections. Not just casting votes, locals allege that Muslim beneficiaries under various Government schemes, such as Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), have multiplied manifold.

Many incidents of mob lynching of innocent Hindu men by Muslims have been reported from these areas. There has also been a rapid spurt of anti-Hindu crimes, including rape and love-jihad, in the last three to four years at Uriamghat and its adjoining areas. Although quite a few girls have been rescued by organisations such as Bajrang Dal, the whereabouts of many others still remain unknown. Muslim mobs have even threatened Hindus from celebrating their festivals. For example, in 2021, a gang of Bangladeshi Muslims pelted stones during the celebration of Manasa Puja at the house of a local Hindu resident. They had taken out swords to scare away the locals and stop the Puja immediately.

As a consequence of this, the majority Hindu population in these regions has been decreasing day by day while the Muslim population has been increasing rapidly, leading to massive demographic change. However, no action was taken by the previous Governments, and the matter persisted, creating serious problems of land encroachment for the locals, especially in the riverbank areas of Pithaghat, Pujabil, and Sonaribil.

Thus, in keeping pace with the Assam Government’s continued efforts to reclaim forest and Government lands, the recent eviction at Uriamghat was an absolute necessity. Hundreds of excavators were deployed by the administration for the operation. It would help address issues of border security, resource misappropriation, and illegal transnational trading practices of the Burmese supari syndicate. Removal of human encroachments coupled with sustained anti-poaching efforts would help preserve vital wildlife habitats and also reverse the trend of shrinking wildlife zones.

Immediately after the first phase of the eviction drive was completed, the All Rengma Welfare Organisation (ARWO) urged the Assam Government to initiate steps for the recognition and restoration of the traditional rights of the Rengma Nagas over their ancestral lands without further delay. They extended heartfelt appreciation to Assam Chief Minister Dr. Himanta Biswa Sarma for the decisive action taken by his government to evict illegal settlers from the Rengma Reserve Forest area. They also appealed to the Government to continue such lawful and rightful actions to ensure the protection of the Rengma Reserve Forest. Approximately 8,900 bighas of land were cleared, and more than a thousand Muslim families illegally occupying it were evicted in the first phase.

To conclude, eviction drives in these ecologically sensitive regions hold immense significance for not only restoring and reclaiming our lands from illegal encroachers but also preserving and safeguarding our natural environment and biodiversity. Indian civilisation and culture have evolved by maintaining a harmonious relationship with the environment, and even today, it is a global leader in the field of sustainable growth and renewable sources of energy. It is true that as a society, Bharat has always been driven by the zeal for excellence in all spheres of life. But, the pursuit of this excellence has never been at the cost of winning over or overpowering nature.

Unlike other foreign religions, Sanatana Dharma is based on respecting everything around us as just another manifestation of the divine energy. That is why we worship our rivers, our trees and plants, and even the animal life in our surroundings. It is therefore only Sanatana Dharma that can save our nature from destruction, for it inculcates the importance of living in harmony with nature and natural surroundings. Instead of politicising, the Assam Government’s recent evictions at Hahila Beel, Paikan, and Uriamghat must be read in this context.

References:

- Assam govt clears 495 acres of encroached wetland at Hasila Beel in Goalpara, The Assam Tribune, June 19, 2025. https://assamtribune.com/assam/assam-govt-clears-495-acres-of-encroached-wetland-at-hasila-beel-in-goalpara-1581631

- Tourism master plan in works for Goalpara's Hasila, Urpad Beels: CM Sarma, The Assam Tribune, June 24, 2025. https://assamtribune.com/assam/tourism-master-plan-in-works-for-goalparas-hasila-urpad-beels-cm-sarma-1582237

- 140 hectares of encroached forest land cleared in Assam town in eviction drive, India Today, July 12, 2025. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/encroached-forest-land-hectares-cleared-assam-goalpara-eviction-drive-2754842-2025-07-12

- Goalpara’s Rakhyasini Pahar witnesses shift from lush greenery to encroachment, The Assam Tribune, July 14, 2025. https://assamtribune.com/assam/goalparas-rakhyasini-pahar-witnesses-shift-from-lush-greenery-to-encroachment-1584690

- Govt structures inside Paikan forest raise eyebrows post eviction, The Times of India, July 18, 2025. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/guwahati/govt-structures-inside-paikan-forest-raise-eyebrows-post-eviction/articleshow/122770595.cms

- ARWO backs Assam’s forest eviction drive, NagalandPost, August 3, 2025. https://nagalandpost.com/arwo-backs-assams-forest-eviction-drive/

(Acknowledgement: A sincere note of thanks and appreciation to Amar for enlightening me on the many facets of the history of encroachment at Paikan and Uriamghat).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. MyIndMakers is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information on this article. All information is provided on an as-is basis. The information, facts or opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of MyindMakers and it does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Comments