Ancient Temples at Sonkh, Mathura

- In History & Culture

- 02:04 PM, Dec 04, 2022

- Amit Agarwal

Mathura, the birthplace of Bhagwan Krishna, is one of the Sapta Puri, the seven cities considered holy and also revered as Mokshyadayni Tirth. Besides being a place of such religious importance, Mathura also had a strategic trade location through which multiple routes passed. The primary route was Uttarpatha (Grand Trunk Road) which connected Kabul to Bengal while passing through Mathura. Another major route was North-South which connected Dwarka to Indraprastha, on which Mathura was a major stop. The dual importance catapulted it into stratospheric fame and it added one more feather to its cap when it spawned an entirely new school of art, appropriately called Mathura Art.

In the Vedic era, too, it was counted among the major cities of Aryavrat, then called Madhuvan, as it was full of fragrance-flowering trees. With the passage of time, the name later degenerated into Mathura. It was also a part of the Sarasvati-Sindhu Valley Civilization, dated to the third millennium BCE as it was just a hundred miles away from Rakhigarhi - a significant site. In the post-Vedic period, it was a thriving centre of the Painted Grey Ware culture (1100–500 BCE) and then the Northern Black Polished Ware culture (700–200 BCE) too. During the 6th century BCE, it was the capital of Surasena, one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas.

Sometime in the 2nd century BCE, it came under Indo-Greeks, colloquially called Yavanas, who had the illustrious king in Menander. However, the excavations at Sonkh, a neighbouring hamlet of Mathura, have yielded coins inscribed with the kings of the Mitra dynasty, beginning with Gomitra, followed by Suryamitra and Brahmamitra and ending with Vishnumitra. After the Greeks, Indo-Scythians conquered Mathura and ruled by king Rajuvala, considered Mahakshatrapa, at the turn of the first millennium. It was during these times that the seed of distinct Mathura Art was sown, which reached its pinnacle a hundred years later during the Kushana period. Mathura became a confluence of Buddhist, Hindu and Jain schools of Architecture with influences of the Persian, Indo-Bactrian and Gandhara art from present-day Afghanistan merging. It is no surprise that more than 10,000 specimens of pottery sherds, terracotta and stone sculptures have been unearthed over the past century from Mathura, half of which have been smuggled abroad.

All along the trade routes, different temples and monasteries were built, which acted as rest stops besides prayer stations. With the passage of time, they also doubled up as gurukuls, universities, social and cultural institutions and even banks. However, the most significant achievement was that they acted as a stamp of Sanatana and the invisible boundaries of Bharatvarsha. Many temples had apsidal architecture, which evolved from apsidal fire altars of the Sarasvati-Sindhu Valley Civilization. Apsidal is a rectangle in the front and a semi-circle at the back, probably for ease in parikrama. Such altars were found in abundance from Banawali, Rakhigarhi and associated sites. All in all, only the deities changed from Agni in the Vedic era to Shiva and Vishnu in Mauryan times, with rudimentary fire-altars giving way to glorious sky-touching temples.

The earliest elliptical temple was found in Vidisha, dating 2nd century BCE. Similar shrines were found in Nagari in Chittor and Etah, Uttar Pradesh, in the 1st century BCE. An apsidal mud platform of the 4th century BCE was also found in Ujjain. At Daimabad, Maharashtra, a shrine complex (1600 BCE), with a mud platform having fire altars and an apsidal temple with sacrificial activity were found. These sites give ample evidence that ancient Hindus loved the apsidal style. However, this does not mean temples of other geometrical shapes were not constructed. Even early Christians seemed to love it, as St Peter's Basilica at the Vatican had the same architecture built in 333 CE.

Apparently, Buddhists also took fancy to such a shape which they extensively carved in rock-cut caves and monasteries from the 3rd century BCE. A few decades later, Hindus also started making temples; many among them were apsidal ones. British later played mischief here and declared that Hindus converted the Buddhist monasteries, sowing a permanent seed of distrust among two sets of brothers. Consequently, many of them feel more at home with Muslims, forgetting that Hindus and Buddhists belong to one sampradaya.

Hindus, rich and talented, started a temple-making spree that reached its zenith during the Gupta period in the 3rd century CE. One such temple complex that came up in the early days of the 1st century BCE was at Sonkh.

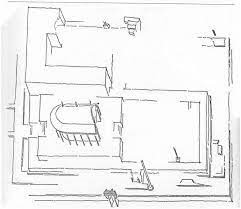

Temple ruins’ condition when excavated in 1960s

In the early 20th century, many pottery shreds and sculptures were found at Sonkh, whose creativity impressed Herbert Hartel, a German professor at the University of Berlin who then decided to excavate the area during the late 1960s. He struck gold when he stumbled upon the ruins of an ancient temple complex comprising two significant temples. Both have a typical apsidal plan which rose to substantial heights. During excavation at Sonkh, Hartel also found more than 3000 terracotta figurines. The most enthralling findings include Salabhanjika sculptures, myriad mother-goddess figurines, mithuna plaques, Naga and Kuber sculptures.

Temple No. 1 was east-west oriented and originally a small structure that was renovated and expanded over time. It is an apsidal structure that stands on a raised platform and measures approximately 9.70 * 8.85 m. It was surrounded on three sides by a thick wall with a secondary shrine. The presiding deity's idol was most likely in the centre of the apse. The temple seemed to contain a large number of plaques depicting Durga as Mahishasuramardini. A red sandstone Matrika plaque was also discovered. It can be inferred that temple’s presiding deity was Matrikas (the Seven Mother-goddesses). It was reconstructed eight times in the 1st century CE, as evident from the distinct floor levels.

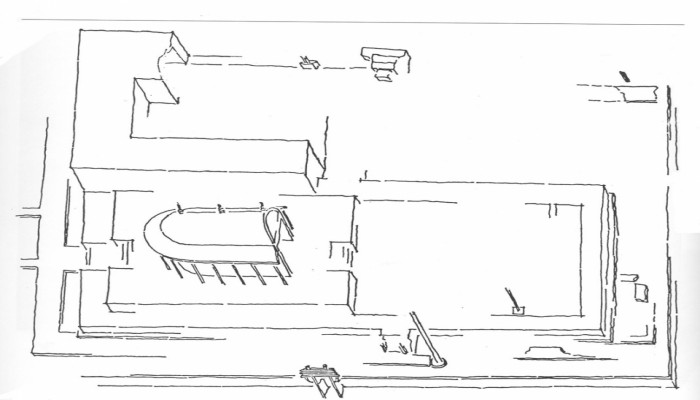

Reconstruction: Temple would have looked like this.

Ruins of the far more elaborate Apsidal temple no. 2 were discovered 400 metres north of the first temple. In its most developed form, the temple would have stood tall on a brick platform, overlooking a pond to the east. The vaulted roof of the apsidal sanctum was adorned with pinnacles. An arch-shaped carved toran dwar adorned the entrance as its beautifully carved remains were discovered. The temple complex was surrounded by a stone railing, the majority of which was carved on both sides. A relief carving of a naga and a nagi seated on thrones, surrounded by attendants and people bowing in obeisance, was also found at the site. This carving, along with several stone sculptures and reliefs, terracotta figurines and moulds, inscriptions, and the top half of a four-sided, seven-headed stone naga image, proves that Apsidal temple no. 2 was a magnificent naga temple.

Present condition

Both temples were at least 2100 years old and one among the most ancient Hindu temples. They were of sheer magnitude, utmost sophistication and exquisite craft. When their ruins were found in the 1960s by Hartel, only the foundation was left. When I visited it last week, even that has gone. Locals are unaware of its importance and consider it just a 100-year-old structure. Though State archaeological department has put up a board, no security was there. Beer bottles were littered there and all around, there is so much filth that it is difficult to even stand there for 5 minutes. The site is also being used to dispose of animal carcasses and is now a far cry from ancient Madhuvan. A little distance away, on the top of a hill, an illegal mazar was looming large over the horizon, which according to locals, has come up recently. It is despite the fact that only a few Muslim families reside in the area. The site needs urgent attention from the ASI as well as the State and Union governments for speedy excavation and restoration activities.

On the contrary, all dargahs, tombs and other Muslim structures are maintained in spic and span conditions across India. There is never a fund crunch or unwillingness on the part of politicians and bureaucrats.

From the very beginning, Hindu temples and their sculptures represent heaven and its eternal harmony. The temples at Sonkh are no exception. Losing them, even though in ruins, will be catastrophic.

As Sanatan sheds its territory, Islam proceeds to encroach on it, almost immediately. And no one is even bothered.

All the images are provided by the author.

Comments