Alphabet or Abracadabra?

- In Interviews

- 05:39 PM, Aug 05, 2016

- MyIndMakers

MyInd Interview: Nilesh Oak speaks to Wim Borsboom

Nilesh Nilkanth Oak had a chance to sit down with independent researcher & Indologist Wim Borsboom, author of: “Alphabet or Abracadabra? Reverse Engineering the Western Alphabet”

He returned from India to Victoria Canada - where he lives - from a four and a half month book promotion and lecture tour to 20 universities, colleges, museums and private institutions throughout India.

Nilesh read his book just after publication last year, June 2015, titled “Alphabet or Abracadabra? - Reverse Engineering the Western Alphabet”, a monograph on his discovery about the origins of the Western Alphabet, how it was modelled after a very early Indian alphabet, at least 3400 years ago,

We reproduce their conversation here:

Nilesh: Wim, you are 72 years old, right? I must say though, you don’t look it, and Wow! you did this huge one-man speaking tour throughout India, organized, from what I gather, pretty much all by yourself, no agents or anything, just assisted by some very helpful outreach students from a number of universities and colleges from… eh… the four corners of India - or was it three? You must be in good health to pull that off - a septuagenarian now.

Well, how old were you when you first became interested in linguistic research, specifically in alphabet research?

Wim: Alphabet research, right? Well, actually (smiling) I must have been four years old or so, around the time when my mom first dropped me off at kindergarten. It was a few years after the Second World War and many Catholic preschools - we were of Catholic background - were run by nuns, and their teaching method was often based on the Montessori Method.

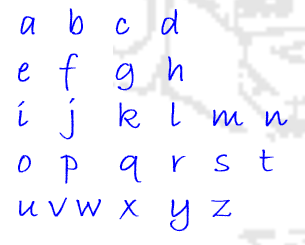

I still remember the way we learned the alphabet, but it was different from the way other kids, in other schools learned it, not like A B C D E - the long vowels, but like a b k d e - short vowels.

We said “k” not “c”.

Often, as you undoubtedly know, we pronounce the “c” as “k” - as in the word “contact”- or as “s” - like in the word “cent”, it depends. It has to do with the “centum - satem isogloss”… Kaiser- Caesar, but, no when I was four or five years old, I was not into that kind of research yet…

Nilesh: (Laughing) yeah, that about the “c” and “k”. That is the same in English. You grew up in Holland - that is The Netherlands, right?

Wim: Yes.

Nilesh: How did you learn the letters, like for writing?

Wim: In the Montessori school we had letters made out of sandpaper. I think that - the roughness - was intended so that we could feel the letters and sort of follow their shapes with our fingers, like we were already getting a feel for writing them. But at home, I remember my brother and me had a reading board with pictures: “aap, noot, mies” (in English that would be “ape, nut, mary”) and small cardboard letters that we had to place in a groove below each picture. But I myself had a special box, a cigar box, which contained cut-out cardboard letters and a folded strip with the alphabet printed on it - in lower case by the way - and I would place each of my cardboard letters in their proper spot while voicing them. When done I would recite the whole alphabet... Sure my mom helped, it was fun.

Nilesh: Not exactly the way we learn the western alphabet in India, I myself learned it by rote. We had one song – ABCD...! But typically no singing. That came later. Nowadays the kids also sing the alphabet song. But we have fridge magnets, those plastic letters in all sorts of colours that you stick on the fridge door. But yours were cardboard? Why was that?

Wim: Well, we had no fridges then, it was just after the war, and I don’t think plastic was invented yet, or at least, it was not used for toys and stuff, that came only after I was 7 or 8.

Nilesh: Did you learn the alphabet song, or just like us, you learned it by rote?

Wim: I already knew the alphabet by heart, but after Montessori school I went to first grade in a normal school, a boy’s school, not Montessori at all. Gosh, I still remember the teacher, she was more than stern. She was like the proverbial drill sergeant, and, she used a wooden ruler, but not for measuring...

Nilesh: Ouch!

Wim: Yeah, like “Ouch!”

Nilesh: Ah, yes I remember, you wrote about her in your book. Tell me what happened between you and her?

Wim: Well, this one particular day our class was practicing the alphabet, reciting it aloud, mistakes included of course. Aloud, I mean... LOUD!

Obviously too loud and messed up for Ms. Gerbrandts, our teacher. It was pandemonium... Then, suddenly, with the ruler that she used to point at the letters on the blackboard, instead she loudly hit her desk and shouted, yeah really, “Order, Order, Order!”, after which she determinedly walked along the desks, her ruler ready... not to measure... not to hit any desks but... well you can guess...

It became frighteningly quiet...

After she had marched through the classroom and returned to her desk, I (I don’t know why, but I did) I stood up from my desk, and - intending to be funny and smart - I asked her,

“Order? Miss, why are the letters in that order, I mean A B C D, why exactly like that?”

To which she answered (while she grimaced in such a way that I was to feel the dummy, not she),

“Well, they are in alphabetic of course... Now, recite the alphabet... PROPERLY, and then SIT.”

I never asked her any questions anymore, instead I silently vowed that I would find out for myself.

Hmm... Come to think of it, that was something we learned at the Montessori school.

Nilesh: You yourself also became a schoolteacher, but that was in Canada. Had you by that time already found out why the alphabet was the way it was - that it contained that hidden pattern that you describe in your book? Did you already know?

Wim: No I didn’t. That I became a teacher was because I followed in the footsteps of my favourite aunt who was a “special education” teacher. So, I went to Teacher Training College in The Hague. But I never taught in Holland… so many things happened…. In any case, we (me and my wife) immigrated to Canada in 1971 and when our son was 3 1/2 years old, we decided to set-up a Montessori school ourselves with some other parents and a Spanish/English ex-nun. I was Vice Principal. Eventually we had a hundred and fifty pupils.

Nilesh: Does the school still exist?

Wim: Pardon? Yeah, it still exist, it goes up to grade twelve now. Anyway, to get back to the alphabet, every time that the children in my class were learning their ABCs, I was always wondering if there would be a 6 year old boy - or girl - asking me, “Mr. Wim, why are those letters in that order?“ and... I would not know the answer...

Nilesh: You did not know the answer then, I guess, but had you been looking for it? There is an India connection right? You got into Sanskrit, did that help you find the answer?

Wim: Yes, it so happened that my wife and I were very interested in the teachings of Sri Aurobindo...

For those who don’t know, Aurobindo Ghose, an Indian formally educated in Cambridge, was at one point - the beginning of the 20th century - a well known Indian freedom fighter, but while in jail - he was accused of setting a bomb against British Imperial Rule - he got, what you call “enlightened” or to say it differently, “He attained liberation of a different kind”. Eventually he became one of India’s greatest philosophers and writers. Anyway, he had written a book on the Bhagavad Gita “The Bhagavad Gita and its Message”, which inspired me to learn Sanskrit... But, “Ugh”, learning Sanskrit, is not so simple for a westerner.

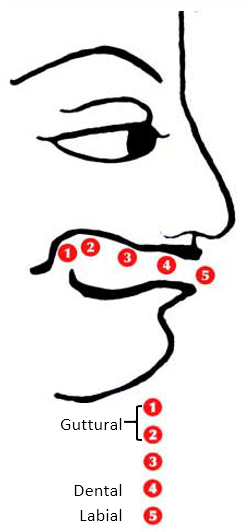

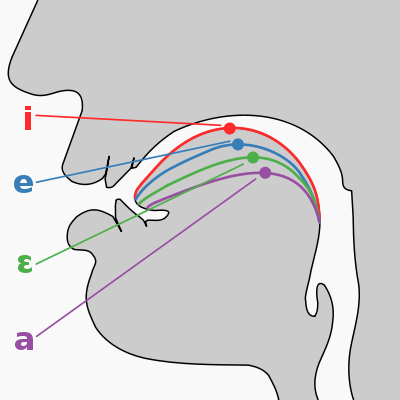

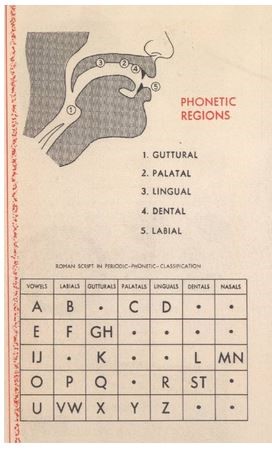

First thing of course, was to familiarize myself with the Sanskrit alphabet letters and lettering, which, as I already knew, differed enormously from the western alphabet: instead of one string of 26 haphazardly arranged vowels and consonants as in the western alphabet, the Sanskrit alphabet is in a tabular format with nine rows or groupings really, of letters - - the letters on each row based on where exactly in the mouth the letters or rather similar sounds of speech - phonemes - are generated.

So, in the Sanskrit alphabet, its letters are categorized in nine groups, for example vowels, gutturals, dentals, labials, etc. - in all 52 letters - in a row format.

Anyway, in those days I was heavily into having the Montessori school kids learning their ABCs, and me learning the Sanskrit Alphabet, but one day, after school, just on a whim, I decided NOT to go straight home, but instead go to a newly opened Espresso coffee shop. Well, you know what they look like, but this one had, in addition to napkins, also - it was the new trend - pencils, crayons and colouring books for the kids.

Anyway, I am trying to relax after a busy day at school, letting go of the children’s alphabet song still vibrating in my ears, and the Sanskrit letters that I am learning, wiggling in my mind’s eye.

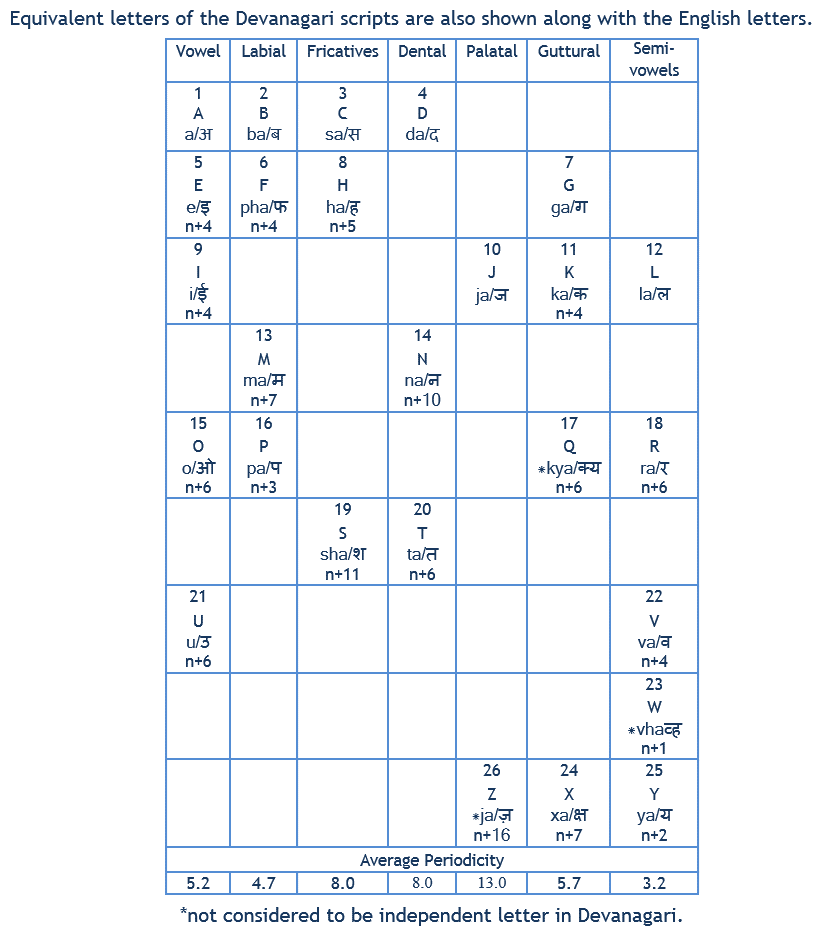

Then without thinking really, I grab a napkin and a pencil and while voicing the letters, I start jotting down the alphabet, the linear western alphabet, but not in one line, but in short rows, yes, like the rows of letters of the Sanskrit alphabet. The way I was doing it, I broke up the long linear alphabet into five rows, each row starting with the next vowel followed by whatever number of consonants there were before the next vowel...

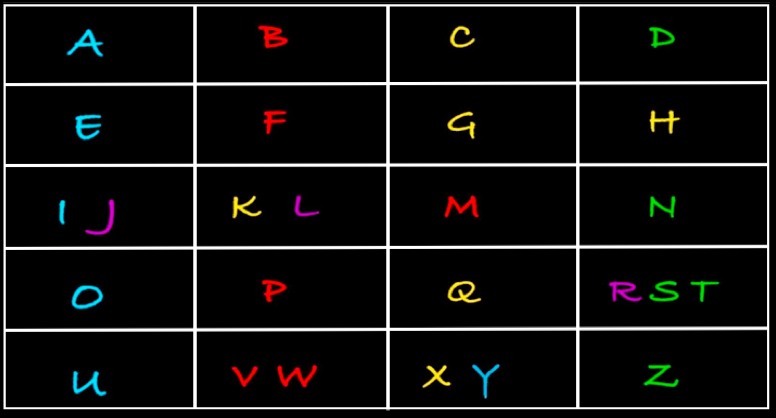

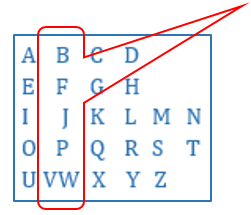

Or in capital characters as follows:

A B C D

E F G H

I J K L M N

O P Q R S T

U V W X Y Z

Like an Excel table, arranged in columns and rows...

Then, just spontaneously, I looked it over, column by column, and lo and behold, I noticed that it had a pattern quite similar to the Sanskrit alphabet structure. The first column of course were the vowels, that was how I had intended it to be, but curiously, they were in the correct order, the way I had l earned it in college:

A E I O U

But, perhaps that was just a coincidence.

The next column though had:

B F J P V

Except for the J, four out of five were labials! Well, just lucky I suppose.

The next column over had:

C G K Q W

That column should be gutturals, but it looked like I was out of luck because the C - pronounced as “sea” - did not fit in with the gutturals. But then I remembered from when I was 4 or 5 years old, that we had learned to pronounce the “c” also as a “k” as in “cool”. Ah…, so now four out of five sounds were gutturals. Good!

What if the next column contained mostly dentals? If so, that would mean that there was too much of a correspondence to ignore...

D H L R X

OK, roughly 3 out of 5!

If I stretched it a bit, the correspondence with the Sanskrit alphabet was close enough, but I was still doubtful, so I started looking a little closer at the whole grid of sounds for more patterns and, perhaps, even anomalies.

Interestingly, certain letters that are close in pronunciation, are next to each other, like:

I and the J - as in “Ian”, “John” and “Jan”.

Also much related are the U, V and W, of which the W really looks like a double V.

What about the G and the H? In some languages they either both sound like an H, or they sound like a rasping G as in the name Allah... which can sounds like “Allagh”.

About the Y, or the way the French say it: “I Grec” - the "Greek I" - I knew that the Y was a later Greek addition to the Latin alphabet.

When I took all that into account, I knew I had something to bite my teeth into… This could use more research, but research that, I was almost sure, would find evidence to support my original hunch that the Western Alphabet was modelled after an - it must have been - earlier and simpler Indian alphabet than the current Sanskrit one. Well, at least I now knew that there were enough correlations between the Latin Alphabet and a Sanskrit one, to tell a kid, if there would be one, who would ask me, why the letters were in that specific order, that I could answer, ”Well, good question... that order comes from Sanskrit! So let’s learn Sanskrit...“. Yeah right...

Nilesh: Impressive, and that in a coffee shop of all places, like Starbucks or Cariboo Coffee, or Coffee Day? Did you think you had discovered something important?

Wim: Yes and No.

No, because I did not think it was very important, like, would knowing this help anyone to be better at language or spelling, or would you be more successful in society, or, when it comes down to it, would you make more money?

Nilesh: Yeah, I can see that... But (laughing) getting back to the scene, you at that table, sounding the letters, did you also sing them, and what did other restaurant guests think? Did anybody notice you?

Wim: Well, (also laughing) I was pursing my lips and making odd noises, and eh... looking like I was writing a furtive note...

No, luckily nobody noticed me. But if so, I am sure they would have thought I was throwing kisses and writing a secret message to be passed on by the waiter to a beautiful lady...

So, no, although…, I did meet the waiter many years later, he was a son of one of my wife’s friends, but... no, he could not recall.

Nilesh: Ha, nevertheless, all joking aside, did you realize you discovered the ancient Indian origins of the western ABC's using a paper napkin and looking funny?

Wim: Yes (smiling), but to prove it, research it, explain it, the whole process, that was serious business!

Let me describe the process.

The first thing though was that the process involved necessary simplification. Why that simplification was needed, will become clear as I describe the process.

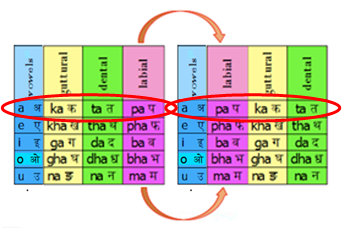

Instead of on the nine rows of the Sanskrit alphabet, I will concentrate on just four, OK? Remember that for later (vowels gutturals dentals labials) And I will number them #1, #2, #3, and #4..., each row representing related, almost similar sounding sounds... like p, b, v, or t, d, th.

Let’s also imagine that an ancient Indian linguist - who must have lived more than 4000 years ago - that he originally developed the earliest alphabet, an Indian one, and that he noticed that the sounds that people use to form their words could be analysed AND categorized. Let’s assume that he categorized those sounds according to where in the mouth they were formed…

Actually, for certain reasons, and why so will become clear later, I assumed that such a person did exist, a likely genius, and that he found it the right thing to do, to start listening for sounds that came from the back of the mouth, the larynx , and that he from there went forwards, ending at the lips...

According to my findings, using my “reverse engineering method” (I will explain later), he came up with the following:

- The vowels - A, E, I, O, U.

- The gutturals - the K, G, NG, etc.

- The dentals - the T, D, N, etc.

- The labials - the P, B, M, etc.

They are aspirated in the larynx, and the shape and size of the mouth opening and to shape of the tongue - how shall I say it - “colour” the sound, modify the sound into differently sounding vowels.

They are formed under the palate area of the mouth, and the shape of the tongue and the location where its bulge touches the palate, alongside different airflow, that modifies the sounds into a variety of gutturals.

They are formed with the tongue touching the teeth in specific ways, and again with different airflow that modifies the sounds into a variety of dentals.

They are formed by the lips touching each other to a more or lesser extent, and that together with differing airflows modifies the sounds into a variety of labials

So, to sum up, each of these sets of sounds - we should really call them “phonemes” - is formed and pronounced in a distinct location inside the mouth while the shape of the tongue, the lips and airflow produces the often slight but nevertheless distinct differences.

Let’s try something, try producing the sounds for yourself, but make sure to use the short sounds, NOT the long ones... So, the A sounds like “a” in the word “car”, the O like “o” in “Tom”, the E is pronounced like the “e” in “net”, the P like the “p” in the word “puddle”, the K as in “cut”, the M like in the word “mum”, and so on and so forth.

So start with #1. A, E, I, O, U...

Nilesh: “A, E, I, O, U”...

You are right, I notice how the lips have an impact, and the opening of the mouth...

Wim: Now try #2… K, G, NG, but remember the K as in “cut”, the G as in “gut”, the NG as in “bangle”...

Nilesh: Let me try, “K, G, NG”...

Thanks to my practice of Marathi alphabets. I can say them without much effort. But I know these are not easy for everyone, even in India.

Yes, the tongue shape changes the sound, and so does the airflow...

Wim: Good, now try #3. T, D, N... as in “turn”, “dung” and “number”…

Nilesh: “T, D, N”...

Ah, definitely, the position and shape of the tongue...

Wim: Now do #4. P, B, M, where the lips and airflow produce the nuances.

Nilesh: “P, B, M”...

Yes, so outspoken, funny how little we are aware of all this... let me do it again, “P, B, M”...

Wim: Ah, there (laughing), it looked like you were throwing kisses at me, just like with me in that coffee shop. Well I won’t take is personally.

In any case, the sounds, or rather the phonemes in the alphabet, are recorded as letters - graphemes in the written alphabet.

So, those rows categorize the human communication sounds from the back of the mouth to the front:

The vowels starting with A, the guttural start with K, the dentals with T, and the labials with P.

Remember A K T P. We need that for later.

So, I sat there trying to find out

- by using my voice

(2) by having the phonemes jotted down on that napkin,

to verify, to check... because I already sensed that something was seriously out of order... and see if the western table of sound categories had the same order column-wise as the Sanskrit sequence that went vowels - gutturals - dentals - labials.

It was upon closer inspection that I saw the problem: instead of vowels - gutturals - dentals - labials:

The western columns went: vowels (A) - labials (B) -gutturals (C) -dentals (D)...

The labial column was out of place... Perhaps I had it all wrong.

Or, as I found out later… my observation was right after all!

Nilesh: Yes, I see, a ka ta pa (or AKTP) became a pa ka ta (A P K T or in the western alphabet ABCD)

In relation to the AKTP sequence of columns versus the western ABCD sequence of columns, I remember that in your book you reported two dreams that you had, and that those dreams somehow showed you how that wrong western order had come about. You dreamt that “you” (whoever “you” were in your dreams), that you were a Near Eastern visiting linguist/student who, one way or another, ended up in ancient India, and that “you” observed that an ancient Indian linguist had scratched marks that represented sounds in the sand, and you asked him if you could get a copy of what he had scratched in the sand. And he did, he made you a copy, copying the marks in the sand onto four palm leaves. That was your first dream right?

Wim: Yes, the first dream showed how that linguist - he was sitting cross-legged - was teaching a bunch of kids in front of him, how to pronounce a variety of sounds while he pointed at the marks that he had scratched in the hard packed sand... Hmm, think of a mother teaching her child to voice its first mumblings.

We should realize that we are not born with a compendium of sounds and a vocabulary of words: except for crying, whatever meaningful we say with exclamations other than shrieks is taught, is acquired.

Anyway, yes, whoever “I” was, after I asked him for a copy, he produced four palm-leaf strips, and he scratched the same marks as the ones in the sand, vertically on the strips - five marks each, so altogether twenty of them.

In the second dream, which had quite an uneasy feel to it, I was back home, in my home country, wherever “home” was, and I was unloading my stuff from the bags that my donkey had carried. But instead of four leaf strips, I found only three… I must have lost or misplaced the one with the vowels. It must have been the vowels because they looked different in shape, simpler, when compared to the marks on the other strips. When I tried to put the remaining three strips in order, I felt particularly uneasy, as I had forgotten which one came first... Then I woke up!

Nilesh : Did you tell anybody?

Wim: Yes, as it was, when I woke up after my second dream, I told my wife. Now, she is very practical, down to earth, but after I told her both dreams, she said, “Go with it, see if it gets you anywhere, and if so, I am sure that your dreams are your clues to find real evidence that support your initial hunches. Maybe you don’t even need the dreams at all. Instead, see if you can work your way backwards in time.

Nilesh: “Work your way backwards in time...” That is what you have been doing...

Wim: Yes so I asked her, “You mean reverse engineering of some sort? Who knows, but yes, some of the dreams’ elements might give me the clues that will lead me to eh... evidence based conclusions.”

Nilesh: Strange as it may sound coming from me, but if I remember well, even Wolfgang Pauli of Quantum Theory had dreams about QT which gave him deep fundamental insights.

Be that as it may, and back on topic, in your book you use the words “abecedary” and “abugida”..., is an abecedary not the same as an alphabet or the ABC, and what is eh... an “abugida”?

Wim: OK, eh... abecedary and abugida. Yes, but wait, first I want to say something more about science inspiring dreams. In any case, you meant James Watson, right?

Nilesh: Yes, that’s him... from the Watson and Crick duo...

Wim: Yeah, Watson dreamt of a spiral staircase, which led him to visualize a double helix as a possible structure of DNA...

It surely is interesting, but OK, back to your other question about the word “abecedary”. That word is used for any linear string of alphabetic characters, which could be Latin, Greek, or Hebrew, Arabic even.

The words “abugida” or “alphasyllabary” though, are used to properly identify any alphabet in which the letters are syllables or almost syllables, like “kha, gha”, etc. They contain consonants and vowels…, the Sanskrit alphabet is totally composed of such letters.

Nilesh: OK, so our Sanskrit "alphabet" is an “abugida”, or strictly speaking our “Devanāgarī” or “Nagari Lipi” alphabet is.

OK, I get that, but now, could you explain how the abecedary string of 26 letters developed from a tabular abugida containing as many as 52 letters?

Wim: An extremely good and astute question. You are on the ball... and you probably think that that got me stumped!

In fact, in a manner, I already started explaining that some minutes ago, remember that you were sounding out those phonemes?

A E I O U

K G NG

T D N

P B M

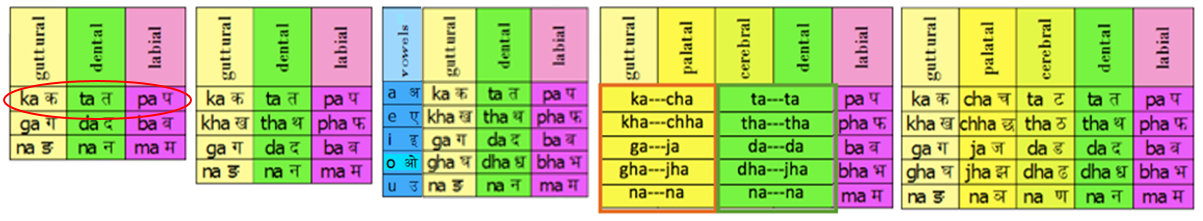

Forget the vowels for now, but those nine consonants, those nine phonemes, they fit a 3 by 3 tic-tac-toe grid. That must in fact have been the earliest compiled alphabet ever. I came to that format from two different angles: (1) the same way as I had you go through it earlier, and (2) by that reverse engineering method I applied.

You see, I suspected right of the bat, when I figured that the western alphabet was modelled after an Indian abugida, that that abugida must have been an early one, simpler, less developed... less developed, but not less genial or erudite!

But before I get into that, I have to again go over that twenty character western abecedary. I consider it to be the earliest western - or more properly identified - the earliest the Near Eastern alphabet.

Remember that within that mix of twenty six letters that we currently use, there were six letters that were interpolations or, let me say, added refinements.

The G and the H are very similar in pronunciation in some Indo-European languages, and that also counts for I and the J, as well as the U, V and W variations, while the Y (the “Greek I”) was a later insertion into the Latin alphabet. In addition, I did not mention yet, the L and R are so related, that - as pretty well everyone knows - Chinese people can hardly even pronounce the R, they use the L instead... Think of “flied lice”.

In the final analysis then, we are left with 20 phonemes.

So, if my hypothesis is right, meaning, if the western abecedary was in its earliest tabular format modelled after an ancient Indian abugida tabular format, then there must have been a time that there was an Indian abugida with only 20 phonemes.

How I found out, and to justify my use of “reverse engineering” in linguistics and specifically phonetics, we need to discuss that “reverse engineering” technique.

Nilesh: Yes, well I guess, everybody knows how the Japanese, Chinese and South Koreans more or less “engineer” and fabricate their products (at least they used to): electronics, cars, cell phones and what not, as they WILL not - DON’T WANT TO - have access to any patents unless they pay costly licencing fees. So, you know as well as I do, they either take the to-be-copied product apart and study its components and copy them, and then take it from there, or they figure out by simple inspection what the product is assembled from and how those parts must have been manufactured and how they fit together, and then, if needed with variations, they will reconstruct that product as “their new original” in their own way and possibly even better than the copied original.

Wim: Right, or instead of producing something bigger and better, say a car, reverse engineering could also produce something simpler, more basic, without frills, bells and whistles, just the essentials.

That is what Japan did with their Toyotas more than half a century ago. From a, for those days, rather advanced American or German car, they came up with a basic model, simpler and, as we found out, more dependable and...rust free.

So, based on what is existent, pretty well everything can be deconstructed into initial or simpler elements.

“This also means that a current sophisticated product shows its developmental history when one analyses its components and construction.”

This also means that a current sophisticated product shows its developmental history when one analyses its components and construction.

After all, our most current electrically propelled driverless car started out millennia ago as a sled on wheels and someone pushing and/or pulling it.

Now, It is this approach of reverse engineering, that I applied to see if I could link my “cleaned up” 20 character abecedary to a complex set of 52 well-ordered Indian script letters distributed over nine rows.

Perhaps, I hoped, I could distil that complexity to just its essentials.

After I pivoted the nine lines of letters (using Excel) into a tabular column & row arrangement, I found that I could distinguish a number of patterns hiding within the larger order.

Subsequently, upon further inspection, when I noticed those deeper patterns - patterns within a pattern - I saw that they represented refinements of a preceding, and thus an - in time - earlier and simpler pattern.

Doing additional iterations in that same manner, meaning step by step subtracting later refinements, I eventually arrived at the most essential pattern, a 3 by 3 table of only nine characters, exactly the ones, the consonants that you vocalized earlier.

Thus, iterating backwards from complex to simple, and consequently also going back in time, I was able to reduce the 52 character scheme down to 30 characters, then to 25, then to 20, then to 12, then to 9 and eventually (beginning 2016) to 3 just K T P.

Some examples of ‘reverse – subtractive’ iterations.

Frome right to left:25 cells, preceded by an intermediate iteration, then 20, 12, 9, 3 (red oval).

(By the way, the vowels have a much different and more ancient origin. think of hooting and hollering monkeys, but that is another story.)

Nilesh: But Wim, is there a historical basis for doing what you did? Is there written evidence that such development took place? WAS the current 52 character abugida, preceded by simpler versions?

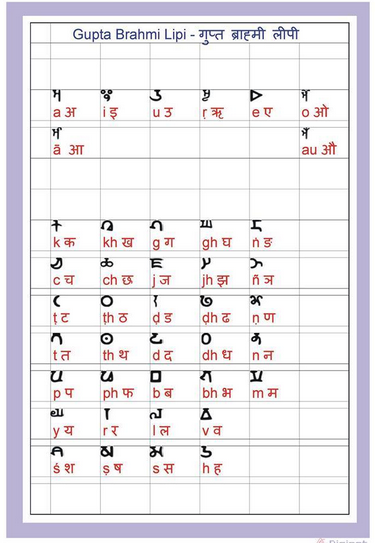

Wim: An early Gupta Brahmi alphabet (left) used 41 characters, before that a Pre-Ashokan Brahmi alphabet was in use with only 38.

So, to say the least, it shows that there were simpler versions ahead of the current 52 character alphabet.

Then there is the famous Indian grammarian Pāṇini, who, some say, finalized the Sanskrit abugida, and who mentioned that his work was an extension and refinement of the work of 64 predecessors. Thing is, that evidence is oral tradition based, we don’t even know what kind of writing Pāṇini used. If anything, it could have been pre-Ashokan Brahmi or, if not, possibly Kharoṣṭhī.

Nilesh: Yes, Panini. I am aware of three different estimates for the timing of Panini – around 2000 BCE, 1200 BCE or 400 BCE.

Ok, I see the reasoning behind your “backwards in time reverse engineering” approach to reach simpler historic or even prehistoric origins. Truly, that makes sense.

Now, do the Western ABC letter shapes also come from Sanskrit letters, or perhaps from Brahmi or Kharoṣṭhī?

Wim: Funny that you mention that. In 2009, when I first, quite informally, presented my discovery at an Indus Valley conference of archaeologists and historians in Los Angeles, I could not convince the archaeologists of the validity of my findings. Mistakenly they thought that I was proposing that the western alphabet letters, their shapes had somehow developed from Sanskrit letters. Well of course not! But because they could not tell their graphemes from their phonemes, their mental grasp was blocked by their... well eh... how shall I put it... ignorance? Two people though got it, and one told me to write my book...

Nilesh: Year 2009 must be very important year. This is the same year when I finally solved the grand puzzle of AV observation of Mahabharata.

But back to the Indus Valley Conference, you also studied the possible migrations by Harappans from the Indus Valley during, or at the end of the Indus Valley Civilization, is it related to what you mention in a footnote of one of your book's chapters: abecedaries in “Eritrea” (North of Ethiopia) and “Yemen”, why?

Wim: I did not want to go into detail in the book, but it is quite possible that one wave of migrations from the Indus Valley ended up in Yemen and/or Eritrea, early abecedaries that are found there might be linked to the Indus Valley. That is highly speculative though, although there are strong indications (mtDNA even) that Harappan migrants landed and settled in those areas.

Nilesh: Wow, migrating people from the Indus Valley... When was that and migrating to where?

Wim: Between 9000 and 3300 years ago, in waves. That is my hypothesis - a radically new migration theory, migrations by sea, coast hugging from the Indus Valley to all of Europe’s coastal lands, sea voyages rather than land routes. In this theory I provide evidence on how Sanskrit dispersed throughout Europe, BUT from coastal areas, from, say, Croatia to Finland and Lithuania, and other coasts in between - also North African coastal areas.

Nilesh: Wow, that's big, too big for now...

So, hold it, let's stick with the ABCs, their seemingly haphazard order because of some mistaken palm leaf placements and a misplaced palm leaf.

It is well explained in your book, almost too much detail, and although I got it the first time I read it, I still had to read certain parts a few times over for it to sink in. It seems so simple, in retrospect, how it all came about, but I guess because we are so used to the linear alphabet, that it is almost a paradigm shift to visualize it in tabular format.

That is 26 letters, but as you said, you were able to weed out the near duplications like U, V, W, and I and J, etc., and that way you could reduce the number to 20 characters that fitted a four by five grid, and then, by reverse engineering you found a 20 grid early Indian abugida which for you turned out to be evidence enough of not only their correspondence but also that the western alphabet was modelled after an prehistoric Indian one.

Wim: That’s a good summary.

About that paradigm shift, yes, but it was a paradigm shift for me too when I first learned the Sanskrit alphabet, its non-linear format, nine rows of letters, 52 in all, instead of 26 and written so strangely.

But then, shift in paradigms produces new insights, new understandings…

Nilesh: It was simpler for me, of course, I grew up with it, Marathi and Hindi are written with those letters.

But, what I meant to ask, were you really the first one who figured out the similarities between the two alphabets - the abecedary and the abugida?

Wim: Yes at first I thought I was, but as I was looking for academic articles that I could quote from and use as references to support my findings and conclusions, I found in all only one source that closely resembled my discovery, in L. S. Wakankar’s monograph “The Traditional Indian Approach to Phonetic Writing” (Bombay.) He published this neat little book on phonetic writing in 1968. When I mentioned it on Facebook, a friend of mine sent me a PDF copy... So neat, quaint really, it seemed from a different age, with wonderful illustrations, one of which I used as the frontispiece illustration in my own book.

Nilesh: Were you disappointed that you were not the only one, or that you were not the first discoverer?

Wim: No not at all. You see, without anybody else also on my track, I would be an odd traveller, and you know, in academia, that is not necessarily a good thing...

Oh, eh, before I forget there was one more person, Rajendra Gupta, a blog writer, also from India. In 2012 he published a large 63 cell table (7 by 9), part of which resembled my 20 letter grid, but he had different intentions with it, he was thinking like Mendeleev and his “Periodic Table of Elements”. Gupta’s large grid featured a host of empty cells in which he hoped to fit more speech sounds than we generally use, possibly phonemes from different tongues, perhaps even click language.

As far as publication goes, date-wise, I was somewhere between the two, but I felt in good company. Nevertheless, when I studied their grids and explanations, both had not noticed the difference in column positions, I mean that the labial column was in the wrong place, nor did they attempt to find if, and if so, how and when the western alphabet could have been modelled after an early India abugida.

Nilesh: Yes, I am in touch with Professor Rajendra Gupta. I am looking forward to long conversations about his research work in upcoming December….

Wim: You mean December 2016? What is the occasion?

Nilesh: I have been invited to present at two conferences in India. One of them is in New Delhi.

But let me get back to the errors in column positions.

Yes, about that error in column positions, and the misplaced column, the one with the vowels. Were they lost and found again? It must be, because they ended up in the grid you reconstructed.

Wim: Ha, I almost wish I had another dream, but I have a daring hypothesis, possibly a risky one.

In my mind, it could be that when that Near Eastern linguist returned home from India to his home country somewhere in the Near East, that he started to demonstrate, possibly even teach his newly found phoneme/grapheme scheme. He may have transferred the phonemic marks back to a grid format, but without the vowels of course, as he had lost them. Then he started teaching what he had to Semitic people, Hebrews perhaps, maybe Arabians... Could that be the reason why they have no vowels in their alphabets?

Nilesh: Phew! Risky indeed! Better not stick your head out! Don’t the Hebrew people claim that their letters came straight from God.

In any case, the vowels must have been found again and “your guy” placed them were they belonged, ahead of the wrongly positioned labials column, next to which were the gutturals and then the dentals.

Wim: You got it. The only thing remaining to be discovered is, when and how the grid’s letters came to be read sequentially, horizontally, row after row, not vertically, not column by column...

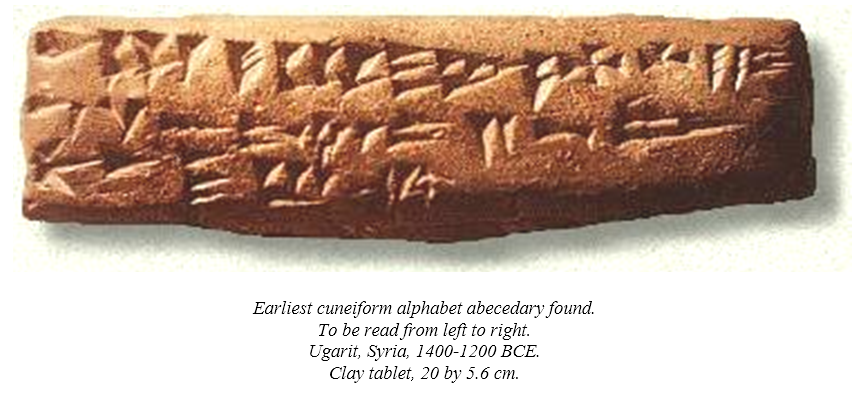

I have no clue on that, only suggestions or best guesses. When searching through any relevant literature for Pre-Latin and Pre-Greek abecedaries, I only found mention of the oldest abecedaries in Syria, Eritrea and Yemen, spread over a period of 500 years from 1400 to 900 BCE.

What has really been a un-overcome-able problem, hampering research into this topic, if there was anything written on it, if there were any records of ancient alphabets, there is a good chance that they would have been found in Alexandria, Egypt. It had a number of libraries, large and small.

Unfortunately, the Royal Alexandria Library had been, accidentally or purposely, burnt down or destroyed, partially and fully, over a period from around the middle of the 1st century BCE to the middle of the 6th century CE by the Romans, the Catholic Church and possibly under Muslim occupation. If such destruction would not have taken place, I can only imagine that... eh... well, that we would not be having this conversation and our kids would recite the alphabet in a different manner.

Nilesh: You mention a period from 1400 to 900 BCE, what is the oldest evidence found so far?

Wim: That was a Ugaritic alphabet clay tablet.

Actually, several were found in 1928 in Syria, in Ugarit, a city that was the centre of a thriving civilization from between at least 1800 and 1200 BCE.

The tablet that I have depicted in my book is from 3400 years ago, it is about 20 cm long and has cuneiform script on it (Ugaritic cuneiform not Sumerian) and it features a 30 character abecedary, it was one of quite a number of artefacts excavated from an ancient school for scribes and from a clay-tablet library.

It is obvious that this abecedary already showed an advanced stage of development, so it not a risky assumption that simpler abecedaries existed much before 1400 BCE. In any case this tablet is the earliest evidence of a real linear alphabet. The thing is, it shows the letters in almost the same mixed up order as our current alphabet, meaning that it must have been developed after the palm leaf mix up by that Near Eastern linguist.

Nilesh: Ah, now I see, that is how you came up with, “...more than 3400 years ago...” as it says on the title page of your book, so that is how you pinned that date? But I hope you do recognize that this estimation is fluid and future research can push that date in further antiquity.

Wim: Well, I would have loved to have pinned an earlier date, but that would only be speculation, so for me 3400 years ago is good enough… for now…

Nilesh: Percentage wise, how close is the current western alphabet to the “prehistoric” one, the one that you reverse engineered? Can I say that... "pre-historic"?

Wim: Yes, you can, but about the closeness, percentage wise…

Let me show a chart from my book:

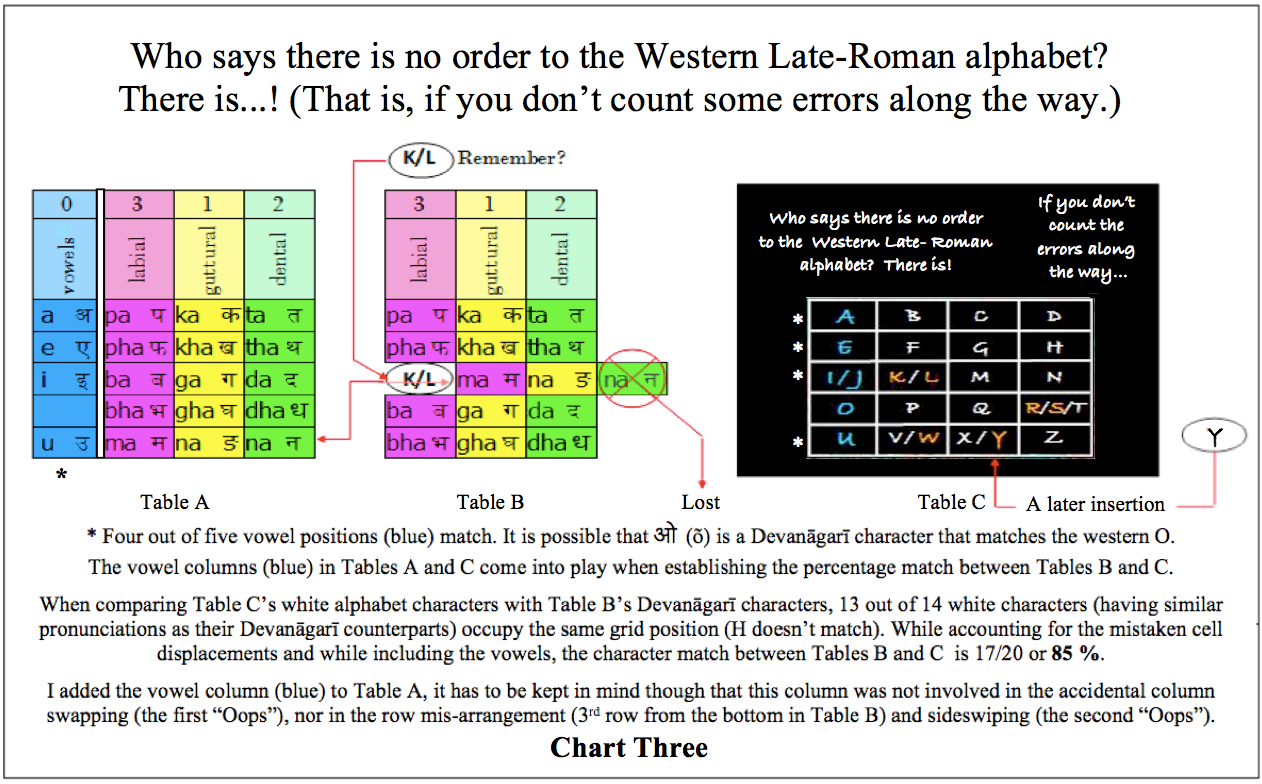

Table B (above middle) shows two more errors that had crept in.

The red arrows show how the bottom row of Table A somehow moved two rows up and one cell over. This then provided an open spot for the K and the L. This way the M landed in the wrong column. The N was initially the guttural NG phoneme, but it turned into the ‘N’, while the nasal ‘N’ got lost… except for the French speakers.

Between Table C (the normalized version) and Table A (the 20 phoneme Indian reverse engineered alphabet from before 1400 BCE) the percentage-wise closeness would be 85 percent.

As to your "pre-historic", whether you can say that? Absolutely, because what I found is from before any written history.

If there is any history, it has come to us by oral transmission which only much later came to be written down.

That also means that even if I have been using words like Sanskrit, Brahmi, Pre-Ashokan Brahmi or Kharoṣṭhī, etc., we cannot know for sure whether the phonemes / graphemes mentioned came from those languages…

That is the reason why the results of this study are still closer to a hypothesis than a theory…

That is also why I used the words “Indian alphabet or abugida” instead of Pre-Ashokan Brahmi, Brahmi or Sanskrit alphabets or abugidas.

Nilesh: I like that, the way you are qualifying your findings… After all history is such an unprovable notion, even if it IS written.

Recorded history might still not reflect the reality of the time that it is supposed to the history of...

Wim: And I like the way you are saying that... excellent!

Nilesh: In closing, do you think that the eh… proper order - the right sequence of letters if no mistakes would have been made according to your findings - that that proper order should be reintroduced and replace the messed up current alphabet that our children still have to learn?

Wim: Oh gosh no, if we would advocate that, that would be rather upsetting, and really it would not make anybody any smarter, and knowing it, it would not advance you one bit in society...

So, I am all for keeping it the way it is.

Nilesh: OK, I agree, but just in case, what would it sound like?

Wim: Ah, there you go… shall I sing it?

A C D B E G L F I K N M O Q R S T P U X Z V

Or something like that.

--

About Wim Borsboom

Mr. Wim Borsboom grew up in the Netherlands in a typical Roman Catholic environment, but from age six on he became increasingly interested in Hinduism, Buddhism, Eastern archaeology and languages.

Since his retirement from a variety of teaching occupations (Teacher and teacher trainer at the Montessori Academy, Microsoft manual writer, software instructor and contract docent at various universities), he has been able to return to what he loved most in early life: eastern religion and culture, archaeology and linguistics. Lately he is focusing his research specifically on the Indus Valley Civilization and a radically new "Out of India" migration theory.

As related to this interview, from the age of being a western preschooler, he sang the alphabet song, but in his case he was not just reciting an age-old rhyme, he always wanted to find out where those ABCD’s came from.

In order to find out, he learned many strange alphabets, and it was in 1975 - at age 31 - when he began to study Sanskrit, that he got his first inkling of why the western alphabet had that peculiar sequence of alphabetic letters, when he started wondering, “Why does E come after D, why is F followed by G?”

About Nilesh Nilkanth Oak

Mr. Nilesh Nilkanth Oak is the author of ‘When did the Mahabharata War Happen? The Mystery of Arundhati’ (2011), where he freshly evaluated astronomy observations of Mahabharata text. His work led to validation of 5561 BCE as the year of Mahabharata War while falsifying more than 120 alternate claims. The book was nominated for the Lakatos award; the award is given annually by London School of Economics for a contribution to the philosophy of science.

He published ‘The Historic Rama’ in 2014.

He writes extensively on ancient Indian history at his blog at www.nileshoak.wordpress.com.

Nilesh studied in India, Canada and USA and holds BS and MS in Chemical Engineering and also executive MBA. Nilesh researches in astronomy, archeology, anthropology, quantum mechanics, economics, naturopathy, ancient narratives and philosophy.

Bibliography

Bett, Steve T., 1996

The Origin of the Alphabet.

Coulmas, Florian, 1991

The writing systems of the world.

Das, Prasad, 2007

www.hindu.com/2007/12/20/stories/2007122054820600.htm.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_alphabet-cite_ref-Himelfarb.2C_Elizabeth_J_2000_1-0

Goldwasser, Orly, Mar/Apr 2010

How the Alphabet Was Born from Hieroglyphs. Biblical Archaeology Review (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society) 36 (1). ISSN 0098-9444.

Himelfarb Elizabeth J., 2000

First Alphabet Found in Egypt. Archaeology 53, Issue 1 (Jan./Feb. 2000) page 21.

Lo, Lawrence,

http://www.ancientscripts.com/alphabet.html

Rao, Rajesh P. N. 2009 (with Nisha Yadav, Mayank N. Vahia, Hrishikesh Joglekar, R. Adhikari, and

Iravatham Mahadevan.)

Entropic Evidence for Linguistic Structure in the Indus Script. Science 29 May 2009: 1165. [DOI:10.1126/science.1170391]

Salomon, Richard, 1995

On The Origin Of The Early Indian Scripts: A Review Article, Journal of the American Oriental Society 115.2 (1995), 271-279 1995.

Salomon, Richard, 1996

Brāhmī and Kharoshthi in The World’s Writing Systems.

Schniedewind, William and Hunt, Joel, 2007

A primer on Ugaritic.

Subramanian, T.S., 2004

Skeletons, Script found at ancient burial site in Tamil Nadu.

http://www.hindu.com/2004/05/26/stories/2004052602871200.htm

Taylor, Isaac, 2003

History of the Alphabet: Aryan Alphabets, Part 2. Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 9780766158474.

“... In the Kutila this develops into a short horizontal bar, which, in the Devanagari, becomes a continuous horizontal line ... three cardinal inscriptions of this epoch, namely, the Kutila or Bareli inscription of 992, the Chalukya or Kistna inscription of 945, and a Kawi inscription of 919 ... the Kutila inscription is of great importance in Indian epigraphy, not only from its precise date, but from its offering a definite early form of the standard Indian alphabet, the Devanagari ...”

Wakankar, L. S., 1968

Ganesh Vidya, The traditional Indian approach to Phonetic Writing.

Woodard, Roger D., 2008

The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia.

Zuckerman, Bruce and Swartz-Dodd, Lynn, 2003

Pots and Alphabets: Refractions of Reflections on Typological Method (p. 89), MAARAV (2003) - A Journal for the Study of the Northwest Semitic Languages and Literatures.

Comments