Ali-ai-Ligang – A Beautiful Agricultural Festival of the Mising Janajatis of Assam

- In History & Culture

- 12:56 PM, Mar 09, 2021

- Ankita Dutta

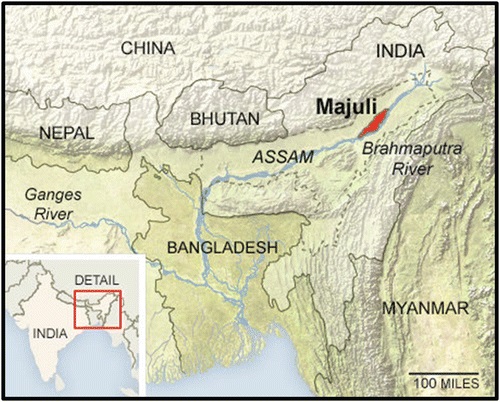

Amid the high of the election fever in Assam, CM Sarbananda Sonowal’s constituency of Majuli (the largest inhabited river island district of the world) recently revelled in the grand festival of Ali-ai-Ligang that was celebrated here with a great pomp and splendour. It began here on a vibrant note from February 17, 2021 at Jengraimukh area of eastern Majuli and continued for almost a week. The Government of Assam under the aegis of the Department of Cultural Affairs, celebrates this festival every year centrally at Majuli. Day-long activities are organised at the Jengraimukh HS School playground in Majuli district, besides an exhibition-cum-sale displaying an array of food items, colourful artefacts and showpieces, beautifully crafted potteries, authentic clothing, etc. of the Mising community that are all put up at the same venue. The Mising Agom Kebang (community house and dormitory) organises a cultural programme later in the evening to entertain the visitors.

In 2018, it was on the occasion of Ali-ai-Ligang that CM Sarbananda Sonowal had formally launched the boat ambulance service in Majuli. It is declared as a local holiday every year by the district administration of Majuli so as to enable all its residents to take part in the celebrations. All government offices, educational institutions, banks and other commercial institutions remain closed here on this day.

Ali-ai-Ligang, popularly known as Mising Bihu among the non-Mising communities of the Northeast, is the most important and widely observed festival of the Mising janajatis of Assam. Recognised as ‘Scheduled Tribes’ under the Constitution of India, the Misings/Miris are designated as the second largest plains “tribal” group of Assam after the Bodos. They are mentioned as Mikir in the Constitution of India. As per the Census data of 2011, the overall “tribal” population of Assam accounted for more than 57% of the total population, and the population of the Misings stood at 5,87,310. Literally, the term ‘Mising’ implies ‘people of the same blood and ethnic origin’.

Picture Credits: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-0620-3_20

Declared as the first island district of the country, Majuli is the cultural and spiritual abode of the Assamese Hindus. Nestled amongst the shifting sandbanks in the lower-middle lap of the mighty Brahmaputra, the name ‘Majuli’ literally implies “land between two parallel rivers”. It has been the cradle of Assamese culture and civilisation for over 500 years. It is also one of the ideal tourist hotspots for travellers visiting Northeast India for the first time, famous as it is for beautiful migratory birds and their habitats, and the most spectacular sunset ever over the sandy undulations of the Brahmaputra. It is a little paradise with unpolluted natural landscapes and tranquil woodlands that are worth to be traversed once in a lifetime for their pristine, flawless beauty. The unique culture of Majuli can be experienced at its best during the Ali-ai-Ligang celebrations in the month of February and again during the annual four-day Raas-Leela Mahotsav that takes place during late October or early November in honour of Sri Krishna.

Once while discussing about the politics behind increasing Christian conversions among the different janajati communities of Upper Assam, especially the Misings, my friend from Dhemaji district and who belongs to the Mising community, drew my attention to the traditional Gomarak or Gumrag/Gumrag So:man (Gumra or Gomarak implies ‘crowd’) dance of the Misings that is especially performed during Ali-ai-Ligang. One of the most distinguished dance forms of the Mising community, the Gumrag dance is a perfect manifestation of their cultural richness and diversity. It reminded me of my own joyous and colourful Bihu dance that is performed with the same energy and gusto as any other Indian dance. They are a fundamental and inseparable part of the rich cultural mosaic of India. My friend further went on to explain the significance of rice-beer and pork among the Misings as we relished on a delicious plate of Mising ethnic cuisine at the Mising Kitchen restaurant situated in the heart of Guwahati city. Any celebration, whether it is a marriage or a religious ceremony or a festival, is incomplete without rice-beer and pork among the Misings.

Having been born and brought up in Assam, I was already familiar with the socio-cultural importance of locally-brewed rice beer among the Karbis, Dimasas, Rabhas, Sonowal-Kacharis, etc. The scene of women selling fresh home-made rice beer in earthen pots has almost become a regular feature at the bustling Beltola Bazar market in Guwahati on every Thursday and Sunday.

Traditional way of rice-beer preparation in the Northeast

The significance of rice can be understood from the fact that almost every other festival that is celebrated in Northeast Bharat is a tribute to the different varieties of rice that are sown at different seasons of the year. In fact, this holds true for most of the festivals celebrated across different parts of India at different times of the year. If Eastern and Southern India are about rice, Northern and Western India are largely about wheat and coarse grains such as bajra, jowar, etc. But rice occupies a special place of significance in these regions too. Vasant-Panchami/Saraswati Puja remains incomplete without eating peele-chawal in many North Indian homes even today. In many parts of Rajasthan, Haryana, and Western Uttar Pradesh, the first visit of the son-in-law to the bride’s home after marriage is marked by the cooking of rice as a special gesture of his welcome.

These are the striking cultural similarities that exist despite the many differences of language, geography, skin colour, etc. among the people of this country. This is the essence of Bharat, aptly manifested through the different agricultural and harvest festivals distinctive to the different geographical regions of India. Ali-ai-Ligang is one such festival of Assam, but quite unknown to many. It heralds the beginning of the Mising New Year or Anu Ditag, and the celebrations sometimes even continue for u pto 10-12 days.

Ali-ai-Ligang, also known as Ligang for short, is an annual springtime seed-sowing ceremony of the Misings. The socio-cultural significance of the festival associated with cultivation and harvesting is implied in its name itself. Literally, Ali-ai-Ligang refers to the first sowing of seeds in which Ali (from the root Alu) stands for roots/seeds/legumes, Ai/Aye/Yai means fruits and Ligang means the beginning of the process of sowing or planting of roots, seeds, etc. Hence, the dance performances that take place during this festival are a replica of the sowing of new paddy seeds in the field for a productive and bountiful harvest. Root-based green vegetables including yams and edible tubers and fruits were the staple food of the Misings in the earlier times when they resided in the hills. Their ways of living and lifestyles steadily changed with the spread of settled agriculture after they migrated to the valley. Rice along with boiled vegetables, meat, fish, and pork cooked in laai-haak (a variety of green leafy vegetable grown in Assam and the Northeast) are some of their signature delicacies.

Ethnically akin to the Adis and Nyshis of neighbouring Arunachal Pradesh and the Tanis of Tibet and Southern China, a large section of the Mising population is to be found residing along the fertile alluvial banks of the vivacious Brahmaputra and its tributaries such as the Subansiri and the Bharali in Assam. Ample availability of water near to the places of their residences has made rice cultivation and animal husbandry the two most important vocations of the Mising community in general.

In Assam, the Misings are predominantly spread over the fertile riverine areas of the districts of Goalpara, Darrang, Sonitpur, Jorhat, Dhemaji, Lakhimpur, Sivasagar, Golaghat, Majuli, Dibrugarh, Charaideo, and Tinsukia in the north bank of the Brahmaputra Valley. They also inhabit a few places in the North Cachar Hills district and Nagaon district of Assam. They are found in smaller numbers along the Lohit, Siang, and Subansiri areas of the East Siang district of Arunachal Pradesh. Some live in the Jaintia Hills of Meghalaya and a few others in the Peren district of Nagaland as well. A majority of the Mising dominated areas in Assam are administered by the Mising Autonomous Council that has been constituted by the Government of Assam under the provisions of the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution.

Most of their major festivals and ceremonies such as Ali-ai-Ligang (the spring cultural festival), Po:rag Purnima (post-harvest festival), Amrok, Taleng Uyu, Ashi Uyu, Dobui:r Puja, etc. are associated with the different cycles of the agricultural seasons. Since agriculture forms the backbone of their survival, the entire Mising society comes together enthusiastically for paddy cultivation beginning from the day of Ali-ai-Ligang onwards.

Ahu paddy was the main crop when jhum cultivation was practised among the Misings in the past. Ali-ai-Ligang was observed with grandeur as a mark of the arrival of the Ahu and the Bau seasons. Sali, Ahu, and Bau are the three main varieties of rice commonly grown in the low-lying alluvial belts of the Mising-dominated areas of Dhemaji and Lakhimpur districts in Upper Assam. Among all these three, the Ahu variety of rice is of greater importance in janajati societies such as that of the Misings; hence, most of their celebrations begin after Makar Sankranti. The celebrations of Ali-ai-Ligang mainly include prayers for a bumper harvest, dances and feasting by both the old and the young alike. Previously, Ali-ai-Ligang was not celebrated at a fixed time or date, but it varied depending upon the convenience and consent of the majority and as well as the climatic conditions.

It was the Adi Mising Bane Kebang, touted as the largest socio-cultural and economic organisation of the Adis and the Misings of Arunachal Pradesh and Assam respectively, which first began the celebrations of Ali-ai-Ligang sometimes in mid-February from the year 1956 onwards. It was from then that a decision was arrived at to celebrate Ali-ai-Ligang annually on Ligange Lange, i.e., the first Wednesday of the Assamese month of Phagun (Phalguna), which is strongly believed by the Misings as the day of Ma Lakshmi, that falls in the Mising month of Ginmur-Polo (mid-February to mid-March as per the Gregorian calendar).

Since then, the Misings have been observing the auspicious Ligang festival in the first week of Phagun, several weeks before the state festival of Assam, i.e., Rongali Bihu or Rongali Utsav in mid-April that marks the first month of the Assamese calendar called Bohag. Bihu is basically the celebration of the change of seasons and the different phases of cultivation that follow accordingly. The festivities of the much-loved Ali-ai-Ligang festival too, are associated with several agro-based rites and rituals. These include the worship of the paddy crop and the ritualistic commencement of the agricultural season. The first Wednesday of Phagun is revered by the Misings as the day of the homecoming of Ma Lakshmi. The melodious songs of love and merriment that are sung during Ligang are called Oi-Ni:tom or simply Ni:tom, which generally consist of only two lines, not necessarily rhyming. Each line in the songs depicts a different emotion. The language is simple yet suggestive, and the style is neat and clear.

The Oi:Nitoms speak of the raw beauty of nature. They are a beautiful reminiscence of the transition of the seasons from winter to spring, and again from summer to winter and vice-versa. The cooing of cuckoos to the blooming of orchids and the fresh scent of earth after the first spell of rains, etc. are some of the integral components of the Oi-Ni:toms that are sung during Ali-ai-Ligang. However, the subject-matter and themes of these songs vary widely and are not restricted to the youth alone.

From the blossoming of love and affection between two young lovers to nature’s beauty, they talk about the ups-and-downs in the life of a man, his happiness and sufferings, and death as the ultimate truth. They are an evocative description of the different experiences, both joyous and painful, of the Misings in their daily lives. It captures the spirit of the festival, of spring, fertility, longing, the beautiful kopou flower (Assamese orchid), and the undying love of Jonki and Panoi, believed to be the Heer and Ranjha of the Misings. Nowadays, most of the Nitoms are also a satirical socio-political commentary on the contemporary state of affairs in the society and its political system. Their expressive beats and tunes share many similarities with the Assamese Bihu songs. Most of them have a tell-tale note, a lovely eiiyoo oh that steeply rises and falls, as if a cowherd is calling out to his beloved who is reaping the paddy. A popular variant of Oi-Ni:tom called Bi:rik is especially sung during seasonal festivals like Ali-ai-Ligang and Po:rag. They describe the different aspects of nature in general and agriculture in particular for understanding them in a comprehensive way.

Ancestor worship is performed on the first day of Ali-ai-Ligang which is also the inaugural day. Offerings of rice, til (sesame seeds), and gur (jaggery) are made to the spirits (Uie/Uyu) of their dead ancestors in a special thanksgiving ceremony. In the Mising cultural belief-systems, there are several types of Uyus/Uies such as Dobur Uie, Urom Uie, Taleng Uie, Gumin Uie, etc. Each of these Uies are believed to cause a particular type of problem or disease, e.g., Dobur Uie is attributed to be the main cause behind all natural calamities like floods, droughts, erosion, death, etc. and the welfare and prosperity of a village community depends upon the blessings of Dobur Uie. Hence, the types of rituals and offerings made to a particular Uie are determined according to its causal nature and functions. It is the Miboo (Mising priest) who diagnoses the underlying causes and the spirits responsible behind the occurrence of any particular problem or adverse phenomena. As a societal norm, women are not allowed to participate in these rituals. The ceremony of ancestor worship among the Misings is known by different names such as Juri, Yumrang Uyu, or Urom Apin. It is generally officiated by the Miboo.

The traditional Mising religion involving the worship of different forces of nature and the sun and the moon in particular, is known as Kewalia or Kalhang or Nishamila. Although Christianity has made strong inroads among the Misings of Assam in the recent times, yet a large section of the Misings here still prefer to call themselves as Hindus. They are followers of the Mahapurusiya-Bhakatiya tradition of Srimanta Sankardeva, imbued with numerous rites, rituals and practices that are unique to the Misings.

A handful of Ahu paddy seeds placed in an Igin (a cone-shaped structure made from bamboo) with si:pag (cotton) is sown in a corner of the field with a Yokpa (Da/sacred sword) by the eldest member of the family early in the morning, seeking the blessings of the Uyus for the birth of healthy children, a rich and abundant harvest, well-being of the domestic animals, and for the overall development of the society. To pacify the Devtas, rice-beer is offered along with fish, eggs, boiled pork/chicken, pithas (cakes) made of bora-saul, and the seeds of the crops sown. Thus, the ceremonial sowing of paddy among the Misings begins from the day of Ali-ai-Ligang. A small patch of land in the eastern part of the field is first cleared by using the Yokpa. It is then decorated with grains of locally-grown brown rice (boka-saul) in a square forming a circular pattern. The rice grains are positioned at appropriate places within the decorated area over which the seeds are sown by chanting the main prayer – Se:Di-Me:Lo, Karsing-Kartag, Abu-Polo, Rugzi-Me:Rang, Guing-So:min, Donyi-Polo – in remembrance of their ancestors, who are believed to bear witness of the seed-sowing ceremony into the womb of Bhudevi (mother earth).

This same prayer is being sung by the Misings in other religious ceremonies and social functions too. Donyi-Polo (Donyi meaning sun and Polo meaning moon) is revered by the Misings as their Easto-Devta (primary God), who is offered prayers on almost every other auspicious occasion. The Misings also invoke the blessings of the mother goddess Kini Nane while sowing the seeds, so as to protect their crops from insects and other natural calamities. Sometimes, naam-kirtan as espoused by Mahapurusha Srimanta Sankardeva is performed by the Misings on the first day of Ligang as a prayer for removing all misfortunes and difficulties that might befall upon their crops and animals.

An earthen lamp (diya) is lit by the Miboo in front of his house on all the days of Ali-ai-Ligang. This is done in honour of the departed forefathers of the Misings for year-round happiness and prosperity. A spade or any other agricultural equipment is covered with a particular leaf called Tora-Paat and then placed in a corner of the field undisturbed till the end of the festival. Upon the completion of the sowing of the seeds, the Misings make a promise to Bhudevi of Guru ku dim, Bhakatak dim, GadhaGhodakupujim, meaning – “I shall offer it to the preceptor, to the devotees, I shall also worship donkeys and mules.” This means that the farmer is not going to enjoy the fruits of his labour alone, but shall rather share the harvest with the rich and the wealthy, the poor and the beggars, and all other living beings alike without being selfish and without any discrimination of class or status. In this way, the festivities of Ali-ai-Ligang begin and the headman of the family returns home.

A fish and meat collection drive is being undertaken collectively by the whole village using knives, bamboo and iron implements, etc. two days before the beginning of Ali-ai-Ligang. In the earlier days, the men would go out hunting in groups, while the women would engage themselves in the collection of edible leaves, vegetables, firewood, etc. for the Ali-ai-Ligang feast. Activities such as ploughing, cutting of trees and bushes, plucking and burning of leaves, collecting vegetables from the fields, fishing, etc. are strictly forbidden on all the five-six days of Ali-ai-Ligang, as a special gesture of respect towards nature. Anti-social activities such as crime, theft and violence on the days of the festival are punishable offences, with punishments ranging from fines to social boycott being the most commonly meted out ones to the offenders. Mising families do not give out any grains (mainly rice) under any circumstance to outsiders during these days, even as exchange or barter. It is considered to be a bad omen that brings financial difficulties for the family. However, money can be parted out in exchange of things.

The main ceremonies of the Ligang begin from about mid-noon after the completion of the sowing of seeds. Dried fish and pork constitute the main menu of the grand banquet that is organised as a part of this festival. Huge chunks of pork are cooked with Notke or Misika leaves, and served in the community feast with rice and Apong (rice-beer). The Misings adore Apong, for it is intrinsically associated with their culture and religion. No religious ritual is observed among the Misings without the presence of Apong. It is sprinkled by the Miboo over the main religious place of worship and other elderly persons sitting around it as a mark of soul purification. During Ali-ai-Ligang, Apong is prepared in sufficient quantities in almost every Mising household. The women get together in the kitchen to prepare Apong and Purang/Tupula Bhaat (boiled rice dumpling wrapped in Tora-Paat into sizeable packets). Both of these are an essential and must-include ethnic dishes of the delicious Ali-ai-Ligang platter.

While Apong/Lau-Paani/Xaaj-Paani is a quite common and popular drink among most of the janajati communities of Assam, Purang or Purang Apin and Namsing or Sopa are two exotic dishes unique to the Misings and both are cooked exclusively during Ali-ai-Ligang. On any ordinary day, the Misings offer Apong to only those guests/people whom they find very warm and welcoming. For the preparation of Purang, a sizeable amount of rice is at first soaked in water after which it is boiled in the same water and then packed into small pieces with Tora-Paat (Alpinia Nigra). These are special wild leaves used as food wrappers or as an ingredient to flavour a dish in the different social and religious festivals of the Misings. They grow in tropical climates and belong to the ginger family of crops. The plant bearing these leaves is considered as sacred by the Misings. If Tora-Paat is not available due to its scarcity nowadays, the rice is then made in banana leaves. Later, it is cooked by either steaming or boiling.

Namsing is homemade dried fish powder which is obtained after first drying the fishes in the fireplace of the kitchen and then grinding them in a wooden grinder (ki:par). It is later packed safely in an air-tight bamboo container. Namsing is used by the Misings in the preparation of different vegetable dishes. Fresh river-water fish which is dried and smoked later on is the main ingredient of Namsing. During Ali-ai-Ligang, Namsing is especially eaten along with rice and Kotil, a kind of pickle made of pounded black sesame seeds, red chillies, rock salt, and a few drops of lemon juice. Kotil serves as an accompaniment to spice up a simple meal comprising of plain boiled rice, boiled laai-xaak, and fried fish. Sometimes, in place of Kotil, Khar (a solution of water mixed with dried banana peel) is also served. Khar is a traditional Assamese detoxifying appetiser that is prepared by burning the stem of the banana tree. It has a specific flavour which is also soothing for the stomach.

Identified with wealth and affluence, Apong is prepared and consumed as a part of the popular culture of the Misings. About 10-15 varieties of plants having immense medicinal value are customarily used in the preparation of Apong by the Misings. However, this number varies from place to place depending upon the availability of all the plants. Previously, the total number of plants that were used to prepare Apong was 50. But this has now alarmingly reduced to less than half the number, which is actually a matter of serious concern from the point of view of the environment and ecology.

To be Contd…..

Title image: Travel Whistle

Comments