A Feminist Reflection On ‘The Kashmir Files'

- In Movie Reviews

- 10:21 AM, Mar 21, 2022

- Rinita Mazumdar

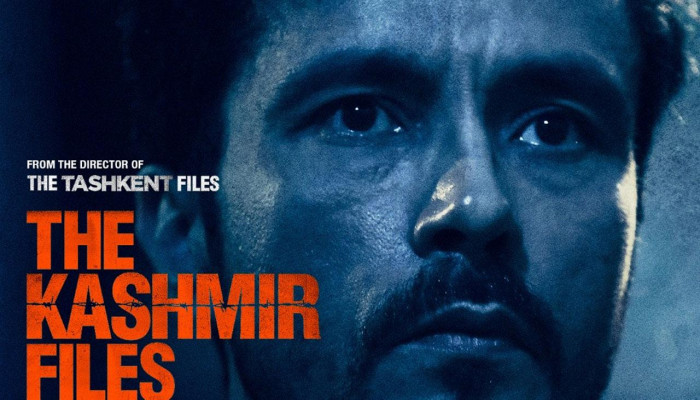

This is not a formal review, neither a professional critique of Vivek. Agnihotri’s film, “The Kashmir Files”. In this reflection I will not analyze the script, filmmaking, dialogues, acting, editing, of the movie. It is more a reflection of my very personal and subjective feelings that was evoked after I watched the movie and came out of the movie theatre supporting my 89 year old mother through the difficult task of climbing up and down the stairs of the movie hall and guiding her safely to the elevator and to the car back home. This reflection is a personal story, where the greater political scenario will not play a large role, although the two intertwine and are in fact inseparable. I saw the movie as a personal journey of a young urban man, of left political conviction, Krishna Pundit/Pandit, descendent of a Kashmiri Hindu family. Krishna’s only living family member, his grandfather, brought him up in exile. He never revealed the truth about the death of his parents and sibling to his only living family member, Krishna.

Part of Krishna’s story is also my history, as a Bengali Hindu, who lost their land, family members, and a sense of belonging, during the partition of India. This is not a history I will write about today, for that history was only partially told by my mother and grandmother to me in snippets. This is a personal story about my loss that I am going to talk about today. It is a loss due to my migration out of my country of birth, my identifying with the left/liberal student community in the University campus, the alienation, the betrayal of an ideology, confusion, the ambivalence, and the finally coming to terms with reality.

Even before I watched the movie, I was familiar with most of the stories for I did a presentation on the events of 1990s and Kashmiri Pundit exodus in the 1990s in Albuquerque, New Mexico together with two authentic Kashmiri women migrants, Shakun and Sunanda. It was a stressful event as one woman, also a migrant, abused us for the presentation for spreading lies, similar to what happened during Krishna’s speech in the auditorium when he was nominated the President. For me the stress doubled because after my presentation, my own left/liberal academic community accused me of Islamophobia and promoting State agenda (the accusers were mostly left/liberal Americans, who have no idea of the history of the Indian Sub-Continent).

In “Mourning and Melancholia”, one of my favourite writings of Freud, he first talked about the ego’s identification and splitting. In this essay Freud talks about two psychical conditions, mourning and melancholia, which have similar symptoms: painful dejection, loss of interest in life and love, inhibition of actions one previously enjoyed. Mourning happens as a result of loss of an object of love due to death, while melancholia happens as a result of loss when the object of love leaves, or is jilted, or slighted. For Freud, mourning is condition that can be reversed by constant therapy and bringing the memories with the object of love to the present consciousness of the mourner; the mourner is faced with the reality of the loss and heals.

Melancholia, on the other hand, is a pathology. The most important difference between mourning and melancholia in Freud is that in melancholia, unlike in mourning, the melancholic critiques himself or herself severely on moral ground. The reason, according to Freud, is that the melancholic’s ego is split and he identifies a part of the ego with the lost object and actually blames the lost object for this condition, who in turn critiques the other part. In melancholia, the ego is completely depleted. There is something one cannot point to how melancholia happens, for the loss is part of the unconscious and cannot surface due to the repression created by the ego. It appears when the ego is loosened in dreams and in therapy.

In the movie, “Kashmir files”, Krishna had no time or opportunity to mourn his loss of family, land, and identity. Although there was no overt sense of mourning, nonetheless, probably a melancholia haunted him from the beginning when we see him as a student among others in the audience listening to Prof. Radhika Menon’s lecture and then going and asking her questions. There is something that is haunting Krishna, and he fills this gap by his performance as the candidate for the President of the student body. He performs what is given to him as the norm within an academic setting. His “home” consisted of his grandfather, whose influence on him is minimizing.

Like Krishna, I felt a loss when I went to Canada as a student. I was too busy with academic to mourn that loss, nonetheless, it haunted me and surfaced when I experienced exclusion or in immigrant communities. I filled my loss with studies and the prospect of a bright future. My loss was not a result of forced exodus or under a threat, nonetheless, there was a loss. In the USA, as an academician and a mother, I felt the loss more intensely. My identity transformed from being a Bengali speaking Indian, to an “Asian”/immigrant (State identification), to a “woman of colour” (left identification). Like Krishna, I covered this loss in various ways, one of which is by becoming part of my left/liberal feminist community. It was also part a legacy of my conviction of left politics, as it was performed in the 1980s in India in elite colleges. Krishna too overcame his alienation via being integrated into the left/liberal University community.

Further, it is hard to overcome and disobey the community values and norms, which gives one a sense of identity and refuge. This is the same as the melancholic’s ambivalence towards the lost object. That is why despite having travelled alone to Canada, I could not throw away my parents wish to marry the groom of their choice. I met and committed myself to my future husband, abiding by the cultural norms, that I physically escaped, but carried within my psyche. As I was growing up, I saw unhappy women performing as happy daughters, wives, mothers. I forced myself to believe that all was well. Krishna, too, was ambivalent from the very beginning, even before he found out about this parents and brothers real cause of death. Yet, his community, the left liberal, the sense of support, the sense of identity he received from this community was an important anchor by which he overcame his own alienation. My own left/liberal/feminist community gave me that sense of belonging and identity as an academician, as someone struggling to deal with an arranged marriage in an alien land, the ups and downs in family life, the pressure of my family, the loss of my sense of identity, the ego depletion, and so on.

Krishna had his doubts from the beginning, but the rhetoric of Prof. Radhika Menon convinced him about what he was confused and ambivalent about. He was convinced he was doing the right thing by being the face of the oppressed minority. So did I, when I was struggling with a failing marriage, the pressures of my academia, and a small child, I went to an anti-Israeli pro- Palestinian march, not knowing fully the nuances of both sides, in fact hardly knowing anything about the history of the complex relationship, just as I was kept ignorant through the history books about my own history of Bengali Hindu Genocide. I parroted with my community, the University hegemonic institution taught me, any talk of these genocides was “Islamophobia”.

Looking back, I now realize, it was so much the fear of my own Islamophobia, as my sense of loss of my community and alienation. Like Krishna, I inherited the hegemonic discourse of the left/liberals without critical thinking and was in what Nietzsche called a “slave morality”. This community, self-proclaimed as the bearer of universal truth develops a need to create the other as “evil” in order to validate his self and show how moral they are. It took me a third party to rouse me from my “dogmatic slumber” (to use a phrase from Immanuel Kant), and realize that things are more complex, more nuanced, and history is not a linear but a circuitous route; truth is never given, but has to be searched for. Krishna’s alienation, confusion, sadness, and coming to terms with reality is not shown in the movie as it is not possible to show such as complex journey in a matter of three hours and twenty minutes, nonetheless, an audience could see his ambivalence, his doubts, and his sadness from the very beginning.

Now a word about the other interesting character that I partially identified with, the character of Prof. Radhika Menon as a fellow academician. I know now that within all institutions, including the academia, critical thinking is coopted and compromised. What I could not identify with is Prof. Menon’s performance of flaunting her spokesperson of the oppressed, for I was never involved actively in student elections or gave any political speech to a large group of audience. Often, the spokesperson for the oppressed relishes her symptom and flaunts it, for it gives them a sense of identity. I too at moment flaunt my position as the spokesperson of the oppressed to show off my ego, while saying that I hold the truth as the ultimate moral authority. This situation has not happened in the way Prof. Menon did, but the possibilities are there.

How would I have asked my students to respond to such public slogan, in defiance of a State, “Hindu men leave, Hindu women stays”, in my feminist theory class, where we regularly teach about women being the bearer and signs of culture. Are these slogans resistances against an oppressive State or are they merely another tool for treating women’s bodies as bearers of culture. Prof. Radhika Menon was not shown in her classroom performing the ultimate moral authority and performing the role of the universal bearer of the spokesperson for the oppressed and passing over the nuances of the complex historical context of who, where, how, and what makes someone a “majority” and “minority”.

I started this writing by saying that I will not go into the script, photography, acting or any technical aspects of the movie. Emotions flooded after watching the movie and I tried to share them using my own feminist framework. As I said, although I knew the material before, but only as an academic presentation, the movie made was a kinesthetic experience of the actual embodiment of brutality. I will now gather what is left of the history of Bengali Hindu genocide and migration. Like Krishna, I will not get an account from my grandmothers, who are both dead, but will make sure to ask my mother, who had very early memories of being in undivided Bengal and how her family first migrated and a part later became refugees. Years have passes since my own losses and traumas of migration and broken family. Healing is a process and not a product. Different people, communities, races, and individuals, heal in different ways. I believe I have started healing via immersing myself in research, writing, painting, and building networks. Memories do sometimes come back in dreams and during the day like fleeting images.

All those whose histories are filled with loss, forced exodus, brutality, pandemics, like that of Bengali Hindus, Kashmiri Pundits, Yezidis, Jews, Native Americans, and indigenous people, will eventually heal but new traumas will invade humanity in some other place and other times, which in turn will need healing. Human beings will probably find ways to heal collectively and not in isolation. In the movie, the majestic mountains surrounding the Kashmir valley stood serenely, like the Witness Consciousness or Sakshi Chaitanya, not partaking of any action, but just witnessing of thousands of years of culture, music, art, literature, community, war, brutality, exodus, massacre, and transformation. In their midst, probably Krishnas and others like him like myself will find their/our lost childhood and their/our Shivas/Shaktis.

Image source: Robet News

Comments