- Feb 28, 2026

- Siddhartha Dave

Featured Articles

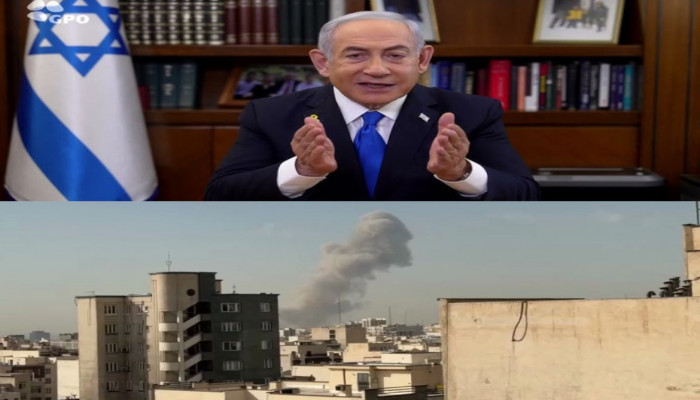

Israel Launches Pre-Emptive Strike on Iran Amid Escalating Nuclear Concerns; US Backs Security Measures

In a decisive move aimed at neutralising emerging threats, Israel, today morning, launched what it described as a “pre-emptive strike” against Iran, targeting strategic assets linked to Tehran’s nuclear and missile infrastructure. Explosions were reported in Tehran, including areas near key government facilities. Israeli Defence Minister Israel Katz confirmed the operation, stating, “The State of Israel launched a pre-emptive attack against Iran to remove threats to the State of Israel.” A nationwide state of emergency was declared, and air raid sirens sounded across Israel to prepare citizens for potential retaliatory missile or drone attacks. Preventive Action Amid Nuclear Escalation The operation follows months of mounting concern over Iran’s advancing nuclear enrichment programme and ballistic missile development. Western intelligence assessments have repeatedly warned that Iran’s missile capabilities, combined with its nuclear ambitions, pose a direct threat to regional stability and global security. Israel has long maintained that it will not allow Iran to acquire nuclear weapons capability. Officials in Tel Aviv have consistently argued that diplomacy must include the full dismantling of Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, not merely temporary limitations on enrichment. The latest strike comes after previous military exchanges between the two countries earlier this year, including a 12-day air conflict in June 2015. That confrontation marked one of the most direct military standoffs between Israel and Iran to date. US-Israel Strategic Alignment The United States has stood firmly alongside Israel in addressing Iran’s nuclear ambitions. In June, Washington joined Israeli operations targeting Iranian nuclear facilities — the most direct American military engagement against Iran in decades. American officials have emphasised that preventing Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons remains a core security priority. The US and Israel share deep strategic cooperation in intelligence, missile defence, and regional security planning. While Washington had renewed diplomatic talks with Tehran earlier this year, American policymakers have made clear that any agreement must ensure Iran cannot weaponise its nuclear programme. Tehran, however, has resisted linking its missile programme to nuclear negotiations. Regional Stability and Defensive Preparedness Iran has warned that it would retaliate against any attack and previously launched missiles toward US positions in the Gulf region. Israeli authorities have temporarily closed civilian airspace as a precautionary measure, reflecting heightened alert levels across the region. Security analysts note that Israel’s doctrine of preemption is rooted in its historical experience of facing existential threats. Given repeated Iranian statements questioning Israel’s legitimacy and supporting armed proxies in the region, Israeli leadership views forward defence as essential to national survival. Western powers have long argued that Iran’s expanding ballistic missile arsenal threatens not only Israel but also Gulf partners, European interests, and broader global security. Implications for India For India, developments in West Asia carry strategic significance. India maintains strong defence and technological partnerships with Israel, while also deepening ties with the United States. At the same time, India has consistently advocated stability, dialogue, and respect for international security frameworks. New Delhi has long expressed concern over nuclear proliferation and terrorism emanating from unstable regions. A nuclear-armed Iran would fundamentally alter regional security calculations, with consequences extending to energy markets and maritime trade routes vital to India’s economy. India’s growing cooperation with Israel in defence innovation, intelligence sharing, and counter-terror capabilities underscores the strategic convergence between the world’s leading democracies in confronting emerging threats. A Defining Moment in West Asia The situation remains fluid, and the coming days will determine whether escalation continues or diplomatic channels re-emerge. However, Israel’s action signals a clear message: nuclear brinkmanship in an already volatile region will not go unanswered. With the United States firmly aligned in preventing nuclear proliferation, and democratic nations increasingly coordinating on security challenges, the unfolding events mark another pivotal chapter in the effort to maintain stability and deter aggression in West Asia. Further updates are expected as the situation develops. (This article was first published in Organiser)- Feb 28, 2026

- Ramaharitha Pusarla